The UK Muslim community feels under attack

Social media analysis shows how Hopkins, Farage and the Daily Mail are alienating and dividing our country.

A few weeks ago, Judith Kerr gave a talk at my daughter's school. The author of the classic children's book The Tiger Who Came to Tea talked of her Jewish father's hurried exit from Germany, days ahead of Adolf Hitler's accession to power in 1933, after a tip-off that he was on the new führer's hitlist.

The rest of the family followed and settled in the UK. When war came, as Jewish Germans, they were tagged as 'friendly enemy aliens', more Jewish than German. They were spared internment, treated decently by those around them and her brother joined the RAF to fight his rejected homeland.

There was a time, then, when we welcomed refugees.

It no longer seems overly dramatic to see our current times as being echoes of the 1930s. This week's murders of Muslims in Zurich, of the Russian Ambassador in Turkey and of shoppers in a Berlin Christmas market were both shocking and familiar – echoes of both our recent and distant pasts – while the rise of populist nationalism has obvious parallels.

What seems less obvious is the sense of inclusiveness that welcomed Kerr into the country even as we fought with her country of birth. There are many within our borders, within the Muslim community, who feel under attack themselves.

The social media analysis company Impact Social looked at social media posts and comments on open news forums within the last 24 hours (post Berlin / Ankara / Zurich, with Aleppo as a continuing soundtrack), covering the activity of 37,000 people who self-identify as members of the UK's Muslim community, to see how they viewed the attacks, and the reactions to them.

Within that grouping, 4,000 posts were connected to the attacks, which equated to 43% of the 'share of voice'. The first thing to note is that is very high, demonstrating a high level of feeling (normally the discussion of terrorism and related issues would cover about 15% of all posts, with the rest the sort of general hubbub common across all social media).

The mood within those posts is pretty grim – 61% of posts were negative, only 12% positive (the rest, neutral commentary of news). That's understandable. The news hasn't been cheering.

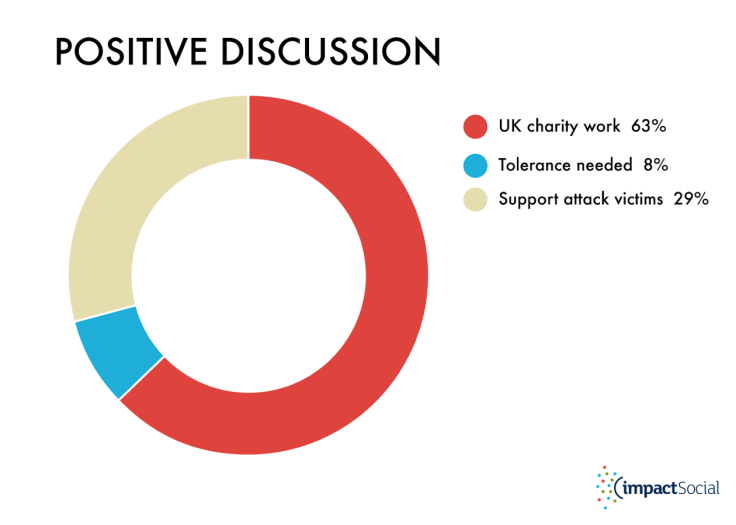

Within that positive sector, 63% were talking of UK charity work and 29% about support for the victims of violence. Humane values walk amongst us, if in small numbers.

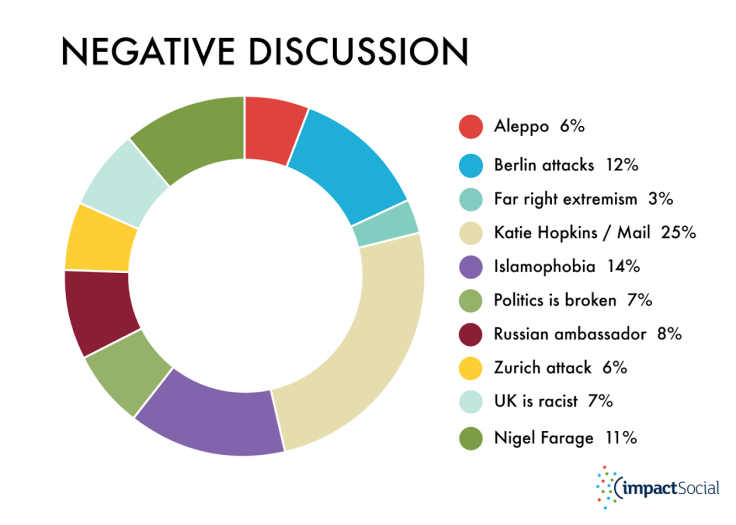

Within the much bigger number of negative posts, the commentary was spread around the atrocities with Zurich attracting 6% of posts (even though that was an extremist attack specifically against Muslims), the Russian ambassador's murder attracting 8% and Berlin 12%.

Those figures seem low, but the pattern reflects the wider media coverage. The media gave those events the same ascending order of importance, the social posts simply reflected that.

But what is striking is the topics that really drove the conversations. Three per cent talk of far-right extremism, 7% feel that 'politics is broken' and another 7% feel that the UK is racist. Another 14% speak of Islamophobia.

These are the numbers of a community that feels under attack. And there's a real feeling that they know who is driving those attacks. The 'Three Horsemen of Intolerance' drive a very significant part of the online chat. Leading from the front. Katie Hopkins and the Daily Mail, in the wake of the settlement on the Mahmood family debacle, take a full 25% of the conversation. That might seem driven by a special case in the wake of Hopkins' apology and the Mail's payment – but there's always a special case with Hopkins and the Mail. And so long as she has a deadline to hit and for as long as she is well-rewarded for her bigotry, there will be revulsion somewhere at what she says, while the Mail is the spiritual homeland for her kind of bile.

That's not to forget their political leader, Nigel Farage, who takes up another 11% of the posts. His attack on Brendan Cox, who he has accused of politicising his own wife's murder and supporting extremism, was a peak in charmlessness even for him, but it's far from out of character.

The connection made from such sources between the Muslim faith and violent extremism is as dangerous as it is false. The Muslim community within the UK clearly feels under attack from such statements (and that is, indeed, the intention). And they are the sub-edited, 'respectable' versions of far greater bile – even worse extremism in the trolling of an entire religion by members of the public online.

Such a process leads to a divided country. A country facing the pressures of extremism and economic uncertainty survives better when it unites.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.