Ukraine Sanctions: How Badly Will They Hurt Russia?

With Brussels and Washington mulling the prospect of further sanctions on Russia, leaders from all sides are hunting for back-up plans.

Russia has moved to create a new free trade zone with Egypt and President Putin has called on his countrymen to create their own card payment system. Meanwhile, the European Union and the United States are moving ahead with their own special trade area.

Recent headlines coming out of Russia make sorry reading for Putin. Capital outflows have reached $70bn [£42bn, €50bn] already this year, compared with a total of $63bn in the whole of 2013. The country's economy minister reported that economic growth could be 0% for the first quarter.

What's more, a World Bank report warned that Russia could contract by as much as 1.8% in 2014, if the crisis were to escalate further. But how badly would deeper sanctions affect Moscow?

There's no denying that tougher EU sanctions could strike a significant blow. Russia's top trading partner is the EU. The bloc accounted for 41% of Russian trade exports in 2012, consisting mostly of gas and crude oil.

Under the current sanctions, which have targeted a number of officials and a bank with close ties to the Kremlin, trade with the EU may take a small hit but this is likely to remain insignificant. For now, the EU is reliant on Russian energy suppliers and the prospect of escalating trade sanctions looks remote.

However, European leaders on both sides of the English Channel have used the current crisis as a platform to propound an escape from dependency on Russian energy supplies.

In Germany, Chancellor Angela Merkel called for the US to increase its energy exports to the EU. Meanwhile British Prime Minister David Cameron said that the crisis has left the EU exposed and should serve as a "wake-up call."

Cameron also insisted that hydraulic fracking for shale gas, a controversial process currently banned in France, Bulgaria, Spain and Italy, will begin this year in the UK.

"Energy independence, using all these different sources of energy, should be a tier one political issue from now on, rather than tier five," Cameron said.

The status quo is likely to remain in the short term but there could be long-term implications for the Russia-EU relationship, regardless of whether more sanctions are imposed. The EU wants to unbind itself from dependence on Russian energy and its leaders are seizing the moment.

Putting the EU, US and Ukraine aside for now, Russia's biggest trading partners in 2012 were China, Belarus, Japan and Turkey.

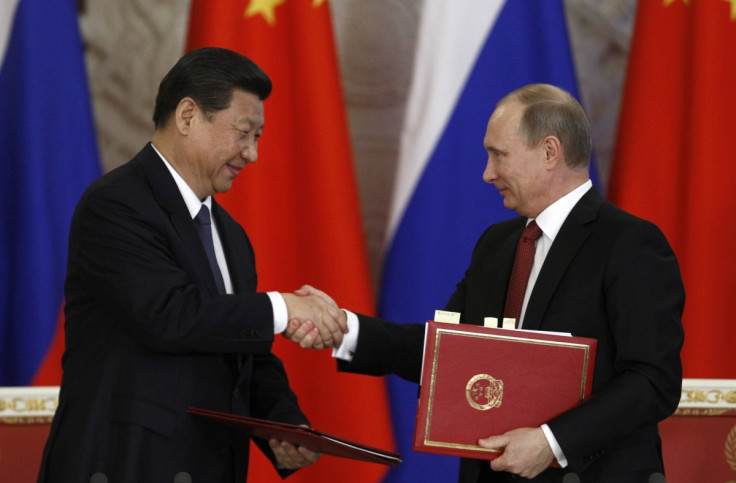

Trade between Moscow and Beijing topped £53bn (€64bn, $88bn) in 2012. The countries signed a raft of trade agreements last year and both leaders publicly called for bilateral trade to reach $100bn.

The Kremlin has reacted quickly to the prospect of further sanctions by moving forward with a gas deal in China, which could see Russia supply 38bn – 60bn cubic metres of gas annually.

While China showed its displeasure at Putin's annexation of Crimea as it abstained on a key UN Security Council vote, the completion of a major gas deal would show that relations between the countries are strengthening. Indeed, while the Chinese wouldn't be able to replace the EU as a gas customer, they could certainly offset some of the loss.

For its part, Japan has tried to stay on the sidelines of the diplomatic scuffle between Moscow and the West. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has met with Putin on five occasions since he returned to power and even attended the opening of the Sochi Olympics. The countries retain mutual energy interests.

In the wake of the 2011 Fukushima disaster, Tokyo closed down its entire nuclear industry and was forced to rely on imports of fossil fuels instead. Much of this new energy comes from Russia and trade between the two countries totalled £14bn (€17bn, $23bn) in 2012.

Moreover, Russian trade with another Bric member, Brazil, has steadily increased in the past few years and shows no sign of abating, despite the Ukraine crisis. In 2013 the two countries completed more than $5bn worth of trade deals, including fertilisers, defence contracts and commodities.

Should the EU and Russia clash again, with deeper sanctions being imposed on Moscow, the Kremlin would feel the pain, but it wouldn't be quite as isolated as some Western leaders are trying to make out.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.