What killed this dolphin? Inside the lab for post-mortems on whales, dolphins and turtles

A young dolphin washes up on a beach in Devon. Here's how two marine biologists investigate its death.

Inside a tiled room next to London Zoo, a young dolphin lies on a table, its skin still wet and shining. Marine biologists Rob Deaville and Matt Perkins wear blue lab coats and plastic gloves. They prepare for the post-mortem, laying out plastic bags and sets of scalpels on what looks like an ordinary plastic chopping board. Their team has done thousands of post-mortems on dolphins, whales, seals and turtles.

The dolphin on the table is one of about 80 to 100 common dolphins that wash up on UK beaches each year. Deaville, project manager of the Cetacean Strandings Investigation Programme (CSIP), picked the animal up earlier that day at Slapton Sands in Devon. Sometimes hundreds of animals wash up at once and sometimes, like in this case, there's just one.

I'm wearing a white lab coat with plastic galoshes over my boots, trying not to breathe too deeply in a room that has a strong, unfamiliar and unpleasant smell. The veterans in the blue coats walk around the body unfazed. Perkins, a senior technician at ZSL, leans in and takes close up pictures of anything that looks unusual.

It's Deaville and Perkins' job to assess the body for signs of disease or injury, spot anything that looks odd, and document everything that could suggest a cause of death. They're looking to gain a broad picture not just of how the animal died, but how it lived.

"It's male, probably about two years old, based on length," Deaville tells me.

"You see this line along the top?" he says, pointing to a subtle groove along the dolphin's flank where the flesh is a little flattened. "The dolphin should be really round. It's nutritionally compromised, I would say. In the back of my head I'm thinking, maybe it's disease?"

There are also a couple of marks on the dolphins' flippers and its dorsal fin, and some raw skin around its lower jaw. These were probably caused after death, Perkins says, through scavenging by animals such as sea birds or crustaceans.

A series of tightly spaced pale rows of lines close to the dolphin's right flipper are marks made by another dolphin. "These are old," Deaville says. "They're conspecific teeth marks. It could be anything – play, sexual behaviour." He opens up the animal's mouth to show its hundreds of tiny pointed teeth.

On the whole, Deaville and Perkins say the body looks very clean, aside from the damage to the head. This already probably rules out bycatch, where a dolphin is caught up in a fisherman's net. There are often a lot more marks on the body where the net cuts into the animal.

Underweight

They roll the dolphin over onto its side before starting the internal investigation. Deaville takes a scalpel and cuts a few neat lines in the skin and peels back a rectangle of skin and blubber. Underneath the dolphin's grey outer colour the skin is black and a millimetre or so thick. Under that is a white layer of blubber less than a centimetre thick.

"That's a bit thin for this time of year. It should be ideally about 1.5cm plus," Deaville says. "It's insulation – keeps the animal warm in the winter, and it's a nutritional source."

Deaville makes a few more cuts and takes another couple of rectangles of blubber from behind the dorsal fin. "This is probably the most important sample we'll collect. It will be analysed for pollutants and contaminates."

Analysing a sample of blubber for pollutants or contaminants can cost between £220 and £1,000. Deaville cuts off two and Perkins wraps them up – one to be sent for analysis and one for the archive. Many persistent organic pollutants are fat-soluble and a lot of them end up in the blubber. These chemicals accumulate up the food chain and are linked to health problems for animals such as porpoises.

But it's hard to say that the presence of pollutants is the definitive cause of death of any individual animal, Deaville says.

"It's tough to link pollution and disease causally. It's like the link between smoking and cancer. You need control groups – animals that are healthy – versus the case group, with disease. For example, with this animal we can't say it's pollution," he says.

But all the samples that the team collects from the animals are analysed and entered into a growing dataset of thousands of specimens, to help scientists study how the factors are linked.

Parasites

Deaville makes some longer cuts and peels off a large section of skin from behind the neck all the way down almost to the tail, and throws it in a yellow sack at the end of the table. The tightly knit muscles under the skin are dark red, packed with a protein called myoglobin, Deaville says, which stores oxygen while the dolphins dive. He points to the line of muscle underneath the dorsal fin.

"You can see here this ridge – this is the spine protruding. You can see that it's lost some muscle as well as blubber. That's a bit of a downward spiral. If it can't swim properly or dive properly then it can't feed properly, so it gets thinner and less able to move."

Lying flat against the muscle layer are a couple of tangles of pale wriggling lines. They're a type of worm parasite common in whales, dolphins and especially porpoises.

"It's not enough to kill the animal, but what we're trying to do is build up a picture of its overall health," Deaville says. "It might be indicative of an underlying problem, in the same way that if you or I weren't feeding properly, we'd start to go downhill."

Dolphins are usually relatively clean animals in terms of parasites, he says. "Porpoises on the other hand are usually chock-full of parasites. The question is, why is that? Maybe it's related to the contaminates passing up the food chain."

Pneumonia

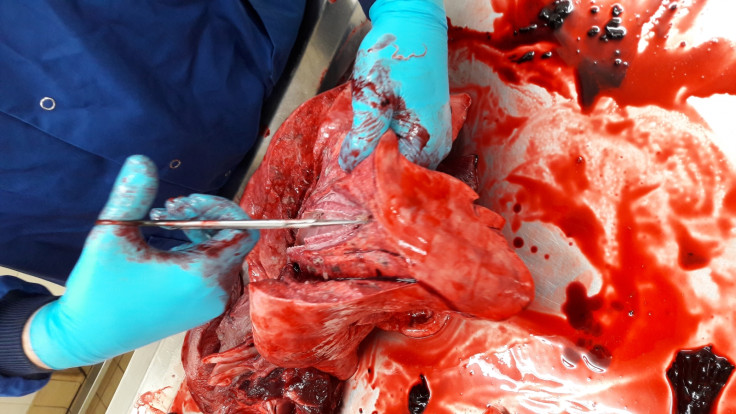

Next comes the part I've been dreading: cutting open the body cavity. Deaville makes a long cut and the dolphin is fully opened. Clear red-orange watery fluid spills out onto the metal table, flowing down to drain at the tail end, where it trickles into a bucket. Nobody faints and Deaville carries on.

He gets a pair of what look like bolt cutters and clips through each of the ribs on the dolphin's exposed side. He cuts and takes out the organs one or two at a time, washing a scalpel in formalin before cutting small tissue samples from each of them that Perkins collects in vials.

The heart, liver, spleen and intestines look normal. He takes a sample of urine from the dolphin's bladder to test for algal toxins. Algal blooms have been known to lead to food poisoning in humans after eating shellfish, as well as causing disease in cetaceans such as dolphins.

What to do if you spot a stranding

If you see a stranded dolphin, porpoise, whale or turtle on a UK shore, first see if you can tell if it is obviously alive or not. If it is alive, call the RSPCA or British Divers Marine Life Rescue if you are in England or Wales, or the SSPCA if you are in Scotland.

If the animal is dead, call the Cetacean Strandings Investigation Programme if you are anywhere in the UK.

Source: SCIP

When he takes out the lungs, it's obvious that one lung is slightly larger than the other.

"It's a bit overinflated, so we're going to open it and see what's going on."

From the outside the lung is a relatively uniform pink colour. Inside, it's riddled with pea-sized green-grey patches. It could be pneumonia caused by parasites or bacteria, Deaville says, adding that the level of infection is on the heavy side.

"There are a few bite marks in the tail area, could have been grabbed," says Perkins. "Maybe an initial source of infection, but impossible to know."

There's no particular sign of stress in the adrenal glands, which often shows up after stressful death as bycatch. They return to the idea of disease and starvation as a possible combined cause of death.

Another sign of malnutrition is an absent thymus. "When animals are under nutritional stress, the thymus atrophies. In an animal this age, we'd expect to be quite prominent," says Deaville . "Again, this is part of the overall poor picture of this animal's health."

Deaville opens up the animal's stomachs next – dolphins have three – to find a few ulcers with more worms in them. There are a couple of tiny fish spines, but not much else.

"Nothing in there. Small spine and a few bits of flesh attached to it. So it hasn't eaten anything recently."

Cause of death

There's no 'smoking gun' pointing to an obvious cause of death of this dolphin, as in many of the cases that Deaville and Perkins see. But there are plenty of markers showing that this juvenile dolphin was in poor condition when it died.

It's thin, with not much blubber and significant muscle wasting. There's little evidence that it had eaten recently, and a minor parasite burden in most of the body, with moderate to heavy disease in the lungs. With no other signs of disease or significant trauma, the most likely scenario is starvation.

"It's the spiral of getting parasites and getting thin and not being able to feed," says Deaville .

There's not much left of the dolphin by the time Deaville and Perkins are finished. The remains, in a collection of yellow bags, will be incinerated. The only parts left of the body will be the samples bagged up, which will go into freezers dotted about the site at ZSL London Zoo, joining those of the 13,000 or so other marine animals that have been investigated in this room.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.