Why Iraq is The Crisis That Has Failed to Raise Its Head in Westminster

The story that hasn't really dared raise its head in Westminster so far has been the nightmare erupting in Iraq.

While Labour and the Tories have an agreed line that sending troops in to help the Iraqi government is "not on the table" and it is for the democratically-elected government to deal with, that is about as far as anyone wants to be drawn into this horror.

But is it any wonder. Politicians on all sides will remember the precise warnings they were given before the 2003 invasion of the possible consequences, not only in Iraq but in the wider Middle East and even at home.

Just one example was the recent confirmation that US intelligence agencies had predicted in January of 2003 pretty much exactly what has happened.

As reported in the Washington Post, the agencies warned that invasion would be likely to spark violent sectarian divides and provide al-Qaeda with new opportunities in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The report, released by the Senate select committee on intelligence also said it "probably would result in a surge of political Islam and increased funding for terrorist groups" in the Muslim world.

And because of the divided society in Iraq between Sunni, Shia and Kurd groups there was "a significant chance that domestic groups would engage in violent conflict with each other".

At home, of course, the Joint Intelligence Committee told Tony Blair in February of 2003 "al-Qaida and associated groups continued to represent by far the greatest threat to western interests, and that threat would be heightened by military action against Iraq".

There were plenty of other warnings, including even the suggestion there could be a knock-on effect on terrorist acts in the UK and US.

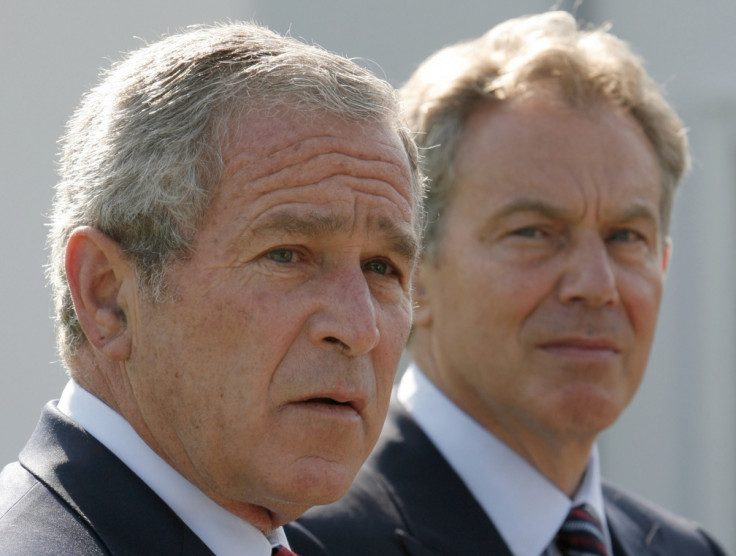

These warnings were certainly taken into account by George Bush and Tony Blair but, as they have repeated at length, they believed the balance of the intelligence, such as it was, pointed in the direction that failure to act would be worse.

It is also the case that the sectarian divides in the region date back to long before the invasion, even before Britain carved up the region with no regard to the divisions during its occupation after the first world war.

Even the Arab spring is now looking less like an upsurge in western-style democracy and more like a return to those old regional battles.

And those 2003 intelligence warnings were clear that invasion threatened to stir up those divisions once again, particularly when the West walked away.

As Blair and Cameron have said since the war, there is little point going back over these arguments, although that is exactly what the Chilcot report will do when it is published later this year, because minds are unlikely to be changed.

The prime minister told MPs during question time: "I have always made the point that I do not particularly see the point of going back over these issues. I voted and acted as I did, and I do not see the point of going over the history books."

And, in any case, claims of "told you so" are not only pointless but verging on the insulting to those now suffering in the region.

Perhaps the final irony, of course, is that if the European Union wanted to engage in any diplomacy over this crisis, one of the key figures it would want to deploy would be its special envoy to the region, Tony Blair.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.