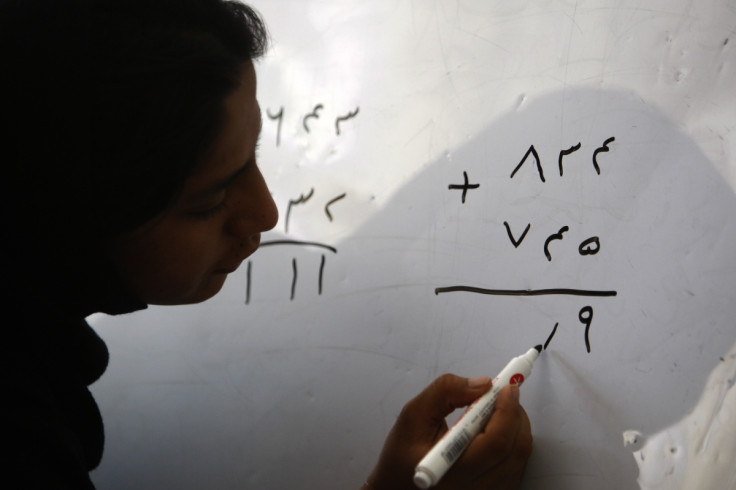

Women Equally Good as Men in Maths, Yet don't get Hired, says study

It may not be true that men are better than women in maths, but people of both sexes tend to endorse the stereotype, a new study says.

The research published in the PNAS journal observed that employers, both men and women, were biased towards hiring men for jobs requiring mathematical skills, even when test results showed an equally good performance by both the sexes.

"Women outnumber men in undergraduate enrolments, but they are much less likely than men to major in mathematics or science or to choose a profession in these fields," the paper says.

"This outcome often is attributed to the effects of negative sex-based stereotypes."

The volunteers for the study were grouped as employers and job applicants, comprising both men and women. The job seekers were required to do quick math exercises, while employers were rewarded with extra money for hiring the best candidates.

In addition, the employers were asked to take an 'Implicit association Test', which measured gender bias through word associations, according to the Huffington Post.

The study noted that men exaggerated their abilities, but on the contrary women were more modest in acknowledging their degree of competence.

Not surprisingly, the hiring team went along with the self-perceptions of the candidates in absence of any proof of test scores, and were twice as likely to choose a man over woman.

After the test scores were declared, the employers were free to change their decision regarding the candidates best-suited for the job.

However, the study found that people, both men and women, are not likely to change their minds even when presented with hard evidence of actual capabilities of the individuals.

Even when the test scores were finally revealed to the employers, lower-performing males were seen to be given preference over female candidates most of the time. Subsequent to the declaration of results, chances of discrimination still persisted by a factor of one-and-a-half.

Also, the paper suggested that those employers who came out to be more biased in the Implicit Association Test, tended not to revise their earlier decision of choosing the undeserving candidate.

"The very people who are biased against women about math, they're also less likely to believe that men boast," Luigi Zingales, the lead author told NY Times. "So they're picking up a negative stereotype of women, but not a negative stereotype of men."

"People don't even learn," he continued, "that they are equally capable."

A global study conducted on 15-year-old teens in 2008, and published in Science revealed that the gap between male and female analytical abilities was associated with gender inequalities existing in different societies.

The countries such as Sweden and Norway where gender-based cultural bias was least, both girls and boys performed equally well in the tests.

The new study led by Zingales serves to supplement the growing body of evidence that cultural prejudices may indeed be discouraging more women from pursuing careers in fields of mathematics or science.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.