When was the worst time to be alive?

The decade saw freakishly bad weather – and if the cold didn't kill you, famine, disease or poverty might.

Historians and climate scientists have unearthed new information that there was widespread disease, famine and poverty in Medieval Europe during a period of intense cold and erratic weather in the 1430s, making it one of the hardest decades to live through in the last millenium.

The study, published in the journal Climate of the Past, looks at on one of the earliest cold periods to be investigated in such detail.

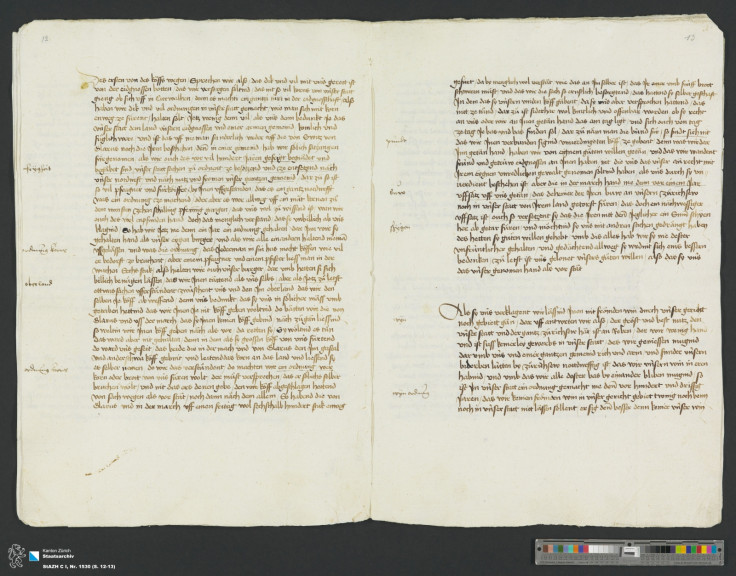

Historians and climate scientists rummaged in historical archives, looked at natural records and used climate modelling to piece together the climate of the 1430s and the devastating social impacts of bad weather.

A cruel time

The 1430s struck particularly hard in the Netherlands, Belgium, northern France and Luxembourg. But in Scotland people were also using fire to melt wine in bottles, and in Central Europe rivers and lakes froze over. Even in southern France and as far south as central Italy the frosts of winter lasted until April.

The dreadful weather killed crops and led to soaring food prices and famine in parts of Europe.

"For the people, it meant that they were suffering from hunger, they were sick and many of them died," says Chantal Camenisch, a historian at the University of Bern in Switzerland.

"Due to this cluster of extremely cold winters with low temperatures lasting until April and May, the growing grain was damaged, as well as the vineyards and other agricultural production."

And if you didn't starve to death, the awful weather could still kill you. "Epidemic diseases raged in many places. Famine and epidemics led to an increase of the mortality rate," she added.

Bad luck

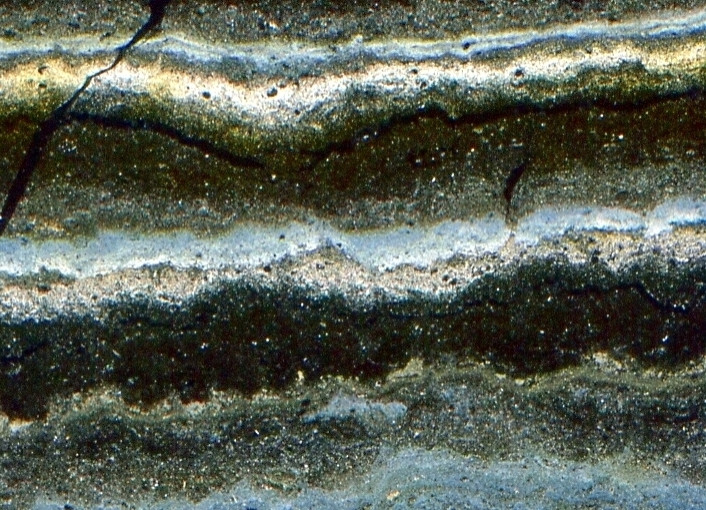

As well as looking at historical archives of harvest records and trade data, the researchers studied natural climate archives such as tree rings, ice cores and lake sediments. They tied this in with climate models to build a picture of the climate of the 1430s in Europe.

"The climatic conditions during the 1430s were very special. With its very cold winters and normal to warm summers, this decade is a one of a kind in the 400 years of data we were investigating, from 1300 to 1700 CE," says Kathrin Keller, a climate modeller at the Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research in Bern.

There were some volcanic eruptions and solar activity during the 1430s, but these events are not enough to explain the overall climate pattern, Keller says. They were instead just natural variation in the European climate. The extreme weather was caused by a combination of natural factors all coinciding at the same time.

Could history repeat?

It's unlikely but not impossible that we could experience an unusually harsh period like this again, Keller says. "Compared with the 15th century we live in a distinctly warmer world. As a consequence, we are affected by climate extremes in a different way – cold extremes are less cold, hot extremes are even hotter."

However, the researchers say that there are still lessons to be learned from the 1430s. "Our example of a climate-induced challenge to society shows the need to prepare for extreme climate conditions that might be coming sooner or later," says Camenisch.

"It also shows that, to avoid similar or even larger crises to that of the 1430s, societies today need to take measures to avoid dangerous anthropogenic climate interference."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.