Parents of babies born with microcephaly demand answers

Brazil is facing a surging number of babies born with abnormally small heads.

Brazil is facing a surging number of babies born with abnormally small heads because of a condition called microcephaly, which some researchers believe is linked to an outbreak of the mosquito-borne Zika virus.

Pernambuco state, in the north east of Brazil, is the epicentre of the Zika outbreak, and also has more than one-third of the cases of microcephaly reported in Brazil since September. Thankfully, the number of newly reported cases here is falling. Every day about five new cases are diagnosed in the state capital Recife, compared with 18 at the peak of the crisis in late November 2015.

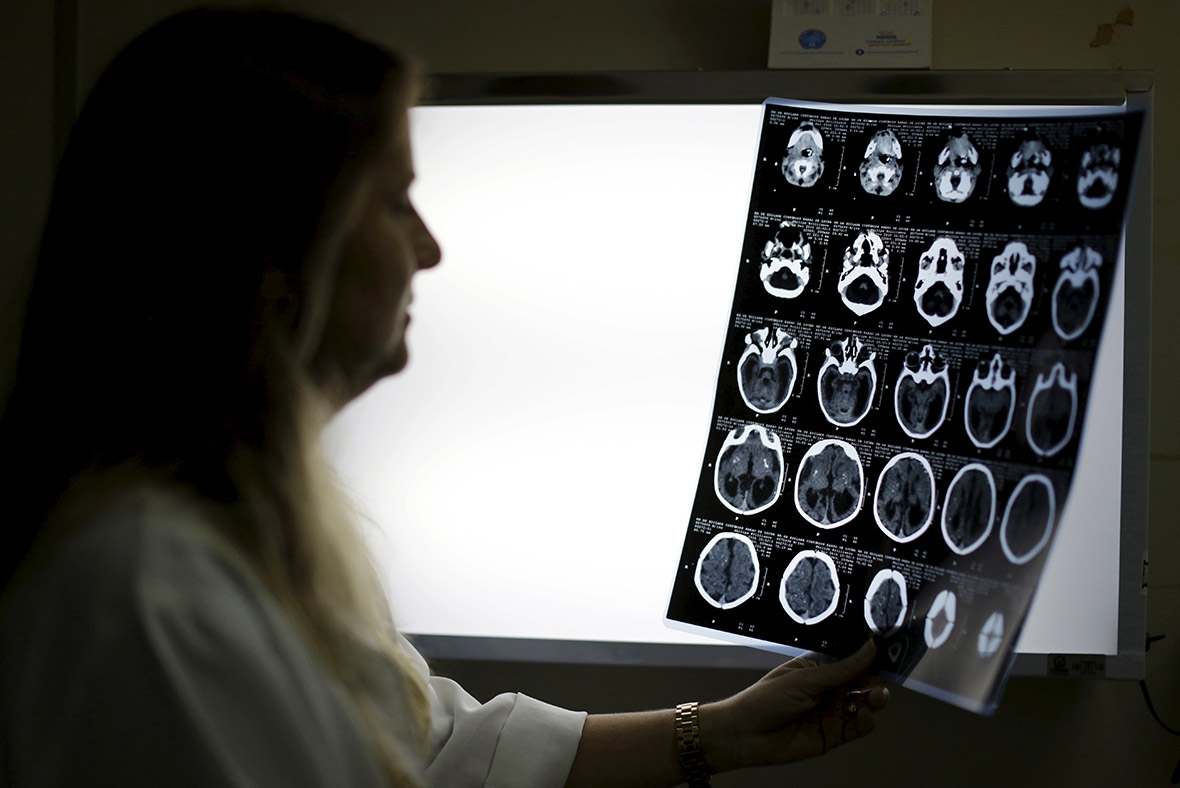

At the Barao de Lucena children's hospital in Recife, a long line of mothers holding their microcephalic babies wait for hours to get an appointment. Vanessa van der Linden, one of only five child neurologists in the state, was the first doctor to notice the alarming rise in microcephaly cases last September, alerting public health authorities. The defects surged in November, when three babies were born with microcephaly on the same night at the dilapidated hospital where she works.

Van der Linden said she was shocked by the extent of the issue. "In the beginning I thought it was a new virus or a new illness, but I never expected it would affect so many and that it would become such a tragedy with so many children affected," she said.

One of her patients is the three-month daughter of 27-year-old toll-booth worker, Gleyse Kelly da Silva, who had a rash, a light fever and a back ache for three days in April last year. Her daughter, Maria Geovana, was born in October with microcephaly. Silva still hopes her baby will learn to speak, but she is frustrated with the public health system, which has yet to provide any therapy. "I think they could help us more by bringing in more doctors, because there are so many babies and even mothers from other towns are coming here to get treatment and they are not managing to get appointments," said Silva.

Hilda Venancio da Silva's son Matheus was born in October with microcephaly. The 37-year-old mother of three said she had no idea that her baby would have the rare condition and felt that doctors at the hospital failed to provide more information. "It was a shock for us because no one knew how to explain it [baby's condition] to us and no one knew what microcephaly was and what it caused. We wanted to know more about how he would develop and no one had that information to give us. We felt completely lost," she said.

The babies, many of whom will eventually suffer convulsions, need brain stimulus therapy promptly to improve their chances of survival. As many as 12 babies have recently died in the state because of the condition. Other complications are appearing among some, including impaired vision and hearing, and badly deformed limbs. Some cannot swallow and the most critical ones have serious breathing problems, said van der Linden.

Doctors at the Oswaldo Cruz University Hospital in Recife were among the first to notice the rise in newborns with microcephaly. It became a daily routine to see mothers here looking for help for their babies. Most of them are from impoverished areas of the state where the lack of sanitation contributes to the proliferation of mosquitoes. Doctors at the hospital say there's a clear correlation between the exposure to the Zika virus and microcephaly but are as yet unable to explain why. The only real advice to women for now: avoid getting pregnant. The World Health Organisation has stressed that any link between Zika and microcephaly remains circumstantial and is not yet proven scientifically.

Researchers have been looking at 4,180 suspected cases of microcephaly reported in Brazil since October. Officials said they had done a more intense analysis of more than 700 of those cases, confirming 270 cases and ruling out 462 others. Health officials did not detail what they found in the 462 cases that were ruled out, but many of them were just premature and undersized. The birth defect can be caused by factors such as genetics, malnutrition or drugs. Infections are also a cause — in the United States, one of the leading causes is cytomegalovirus — although Zika-like viruses have not previously been linked to microcephaly.

Brazilian officials said the babies with the defect and their mothers are being tested to see if they had been infected. Six of the 270 confirmed microcephaly cases were found to have the virus. Two were stillborn and four were live births, three of whom later died, the ministry said.

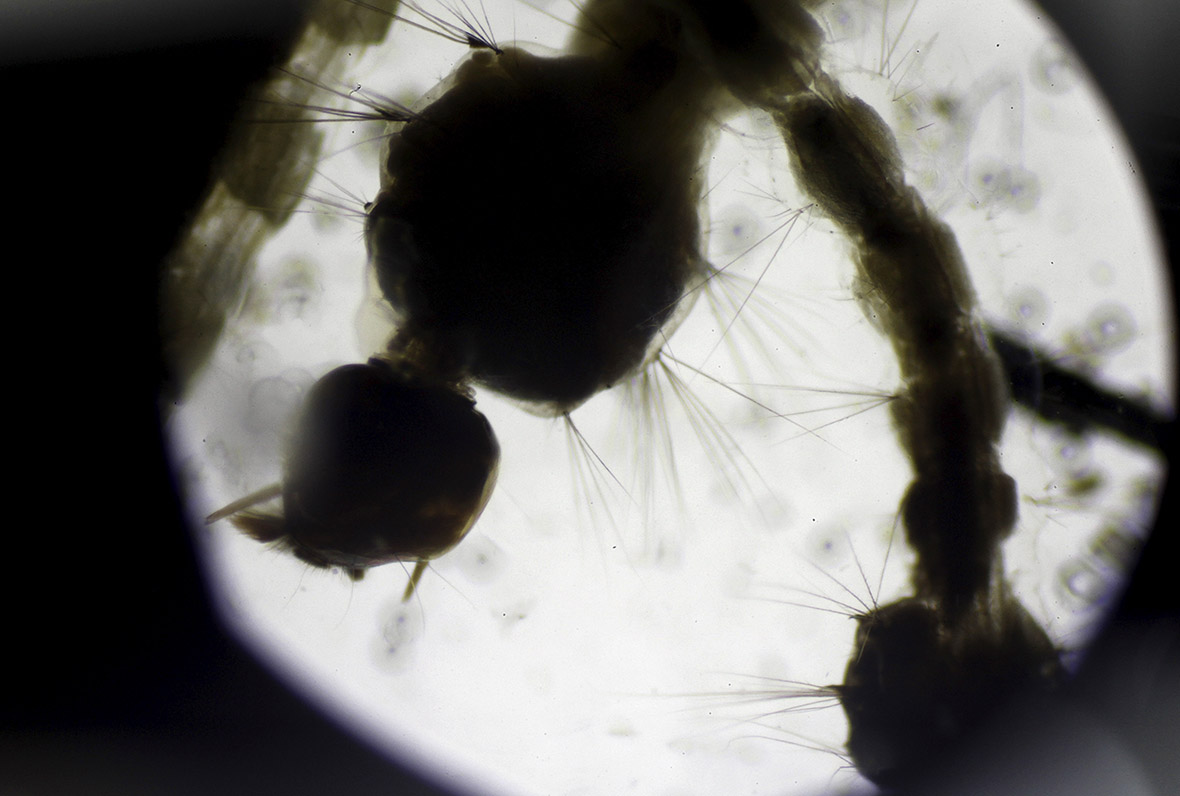

The Zika virus has arrived only recently in Brazil, but the mosquito that spreads the disease, the Aedes aegypti, is well known and an old problem for health authorities here. It's the same mosquito that carries the virus of dengue fever and yellow fever. The army was called in to help health inspectors look for breeding grounds. It's not easy: any container of standing water can hold eggs and larvae.

Eighteen countries and regions in the Americas have confirmed cases of Zika virus infection, including Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, Venezuela, Barbados, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guatemala, Guyana and Haiti.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.