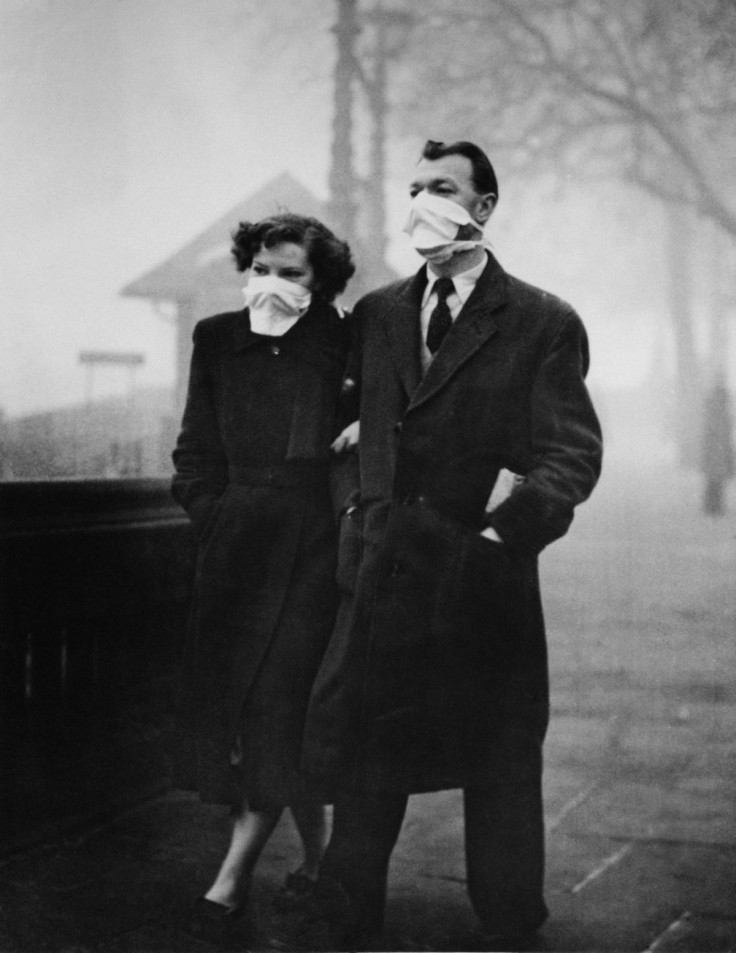

Air pollution knocks a decade off life expectancy

People who die from air pollution typically lose nine to 11 years of life.

An increase of just 10 micrograms of carbon pollutants per cubic metre is enough to reduce life expectancy by nine to 11 years, a new study finds.

Tiny particles of partially burnt carbon, called PM 2.5, are linked to chronic lung problems, heart conditions and some cancers. The difference between being inside a city and outside a city is roughly equivalent to 10 micrograms per cubic metre of PM 2.5. People in inner cities are frequently exposed to much greater levels of PM 2.5.

Previous EU figures have come out with an estimate closer to an average of 1 to 2 years of life years lost to air pollution across the general population. A reanalysis of the data by Mikael Skou Andersen of Aarhus University in Denmark found that the average was closer to nine to 11 years, when you take into account who actually dies of air pollution.

"About 70 or 80% of Europeans are exposed to these high concentrations," Andersen told IBTimes UK. "In the most polluted areas there is several times this level."

But that's not to say that 70-80% of people will die 10 years early because of air pollution. It's only those who do end up dying of air pollution that will lose a decade of life.

The finding overturns the commonly held idea that only people who are already very sick tend to lose just a few months of life due to air pollution. The reality is that it is cutting people's lives significantly shorter.

"In the past [the EU] has made assumptions rather than actually trying to clarify the problem," Andersen said.

Although this new calculation of the effect of air pollution on life expectancy is stark, it shouldn't come as a surprise.

"We know that we have these high concentrations and it's been in discussion for a long time. Now also with the discussion over diesel vehicles and the commercial issues there, illustrated by 'diesel-gate', with car manufacturers downplaying the real emissions," Andersen said.

"I think it's important to deal with these implications, and there are some serious implications from the levels of air pollution that are prevalent across Europe."

However, Heather Walton of Kings College London welcomed the study but cautioned that Andersen's calculation is not comparing like for like with the previous EU estimates. The new calculation focuses on a subset of the population that is affected by the conditions triggered or exacerbated by air pollution – people with lung cancer, asthma or heart conditions, for example.

"A lot of work in public health is looking at the risks to a population as a whole rather than a subgroup. If you're thinking in terms of, say, designing a policy to reduce air pollution, you would want to know the total impact on a population."

The research is published in the journal Ecological Indicators.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.