Climate Change Decimates Spending in Sub-Saharan Africa

Some of the poorest countries in the world are shelling out a lot of money to address climate change, leading to a cut in their spending for vital areas such as education and health, according to a report.

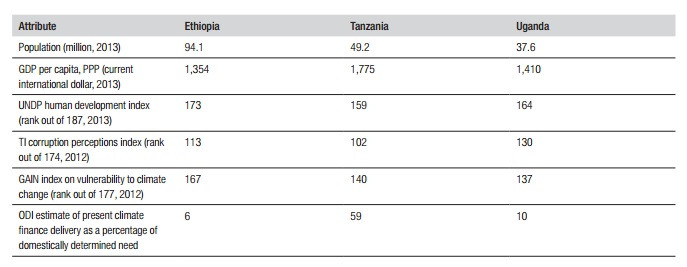

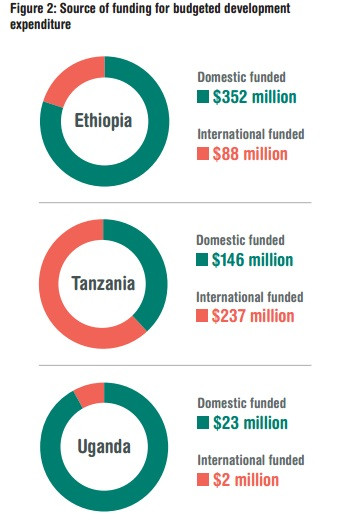

The report by the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) based on research from three countries in sub-Saharan Africa – Ethiopia, Tanzania and Uganda – shows these countries' expenditure on climate change adaptation that is taking place through national budgets represents a considerable burden on their limited revenue base.

Over four years from 2008-11, Ethiopia committed 14% of its national budget, equivalent to half its spending on primary education, to address climate change. Meanwhile, Tanzania spent 5%, which is almost two-thirds of its health spending.

While rich countries are investing heavily in climate change adaptation, poorer countries have to address the challenge with far fewer resources, the report said. Between 2010 and 2011, Britain spent about £700m ($1.14bn, €889m) on flood defences.

"Some of the impacts of climate change that will affect food security, water availability and human health are already evident. Looking ahead, there is a danger that climate change will compromise efforts to eradicate extreme poverty and to reduce the vulnerability of the world's poorest people," the report says.

Meanwhile, international financing for poor nations to address climate change has been limited. Only $5.7bn out of a total of $31.9bn allocated global funding during 2010-2012 went to adaptation projects, according to an analysis of Fast-Start Finance.

Several dedicated multilateral climate funds have been created, including the Least Developed Countries Fund, the Special Climate Change Fund, the Adaptation Fund and the Pilot Programme for Climate Resilience.

However, total disbursements from these funds over the period 2008-2011 to countries in sub-Saharan Africa amounted to less than $130m a year.

"The relative neglect of adaptation matters at several levels. Most obviously, it limits the resources available for poor countries to protect their people, and their social and economic infrastructure, from climate change," the report says.

The report concludes that existing international public finance for adaptation is inadequate in provision and inefficient in delivery mechanisms.

"What is needed is an approach that delivers finance at a scale commensurate with the risks to be addressed through a mechanism that creates incentives for effective delivery."

ODI added that international support should, at a minimum, match the level of domestic public spending relevant to climate change in the most vulnerable countries.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.