Colombia's Brexit: 2 maps that explain why voters said 'No' to peace deal with Farc

Colombians and the wider world have been shocked by the result of the referendum

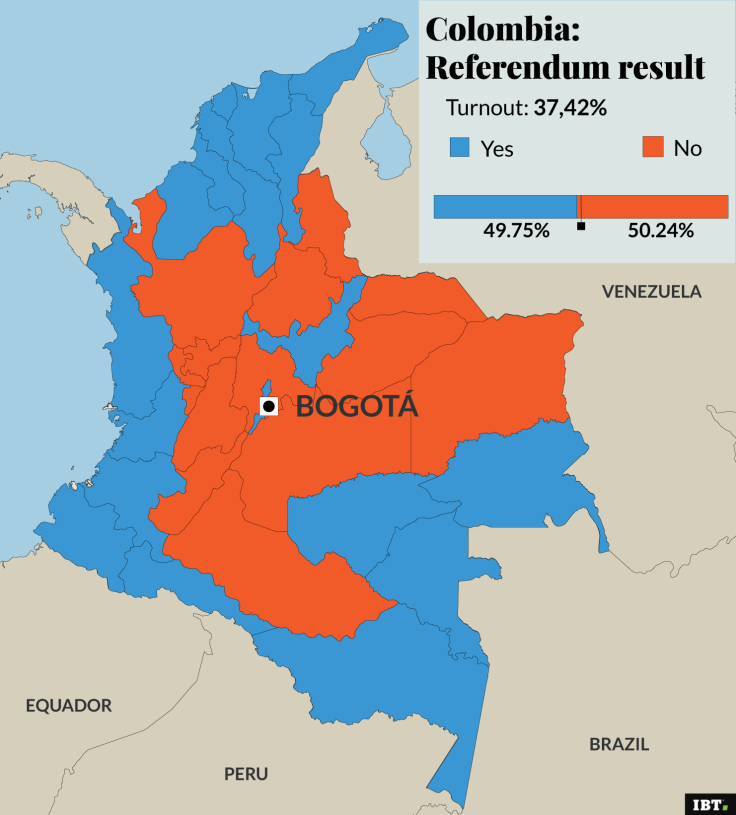

Juan Manuel Santos went into the referendum on Sunday expecting the Colombian people to rubber-stamp his agreement with Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc) to end more than five decades of conflict – but voters had other ideas. In a result that has shaken Colombia, citizens voted to refuse the deal, 50.2% to 49.8%.

It has been called "Colombia's Brexit" in that the expectations ahead of the vote were a comfortable win for 'Yes' backed by at least two-thirds of the population. A similar result had been predicted on June 23 when 52% of British voters opted to leave the EU, confounding expectations that Remain would win by a landslide.

Colombia's result was close even by Brexit standards: the final tally was 50.2% to 49.8%, a difference of just 54,000 votes out of a total 13 million cast. But just as in Britain, Santos has pledged to uphold the result: after four years of talks with Farc on which he has staked his reputation, the president is going back to the drawing board.

Both Farc and Santos have pledged that the ceasefire that has been in place since 29 August would remain and analysts were buoyed Monday by a statement from the rebel group's leader, Rodrigo Londono – known by his nom de guerre, Timochenko – that Farc did not want a return to war.

But just as "Brexit means Brexit" in Britain, so "No means No" in Colombia. The deal, brokered in the Cuban capital of Havana, had been heralded across the world including by UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon as an opportunity to end the world's most prolonged conflict. It is now in tatters.

'No' has claimed there is a Plan B - now they will have to come up with what that looks like.

"I think that the previous phase of talks between and government and Farc in Havana is done," said Kristian Herbolzheimer, director of the transitions to peace (Philippines and Colombia) programmes at the Conciliation Resources think-tank in London.

In the wake of the vote, Santos has pledged to continue his efforts to secure a deal with Farc but it is likely that his nemesis and leader of the No camp, Alvaro Uribe, will have to be part of any new talks. "Uribe and those campaigning for No won and they need to be part of any further conversations," said Herbolzheimer.

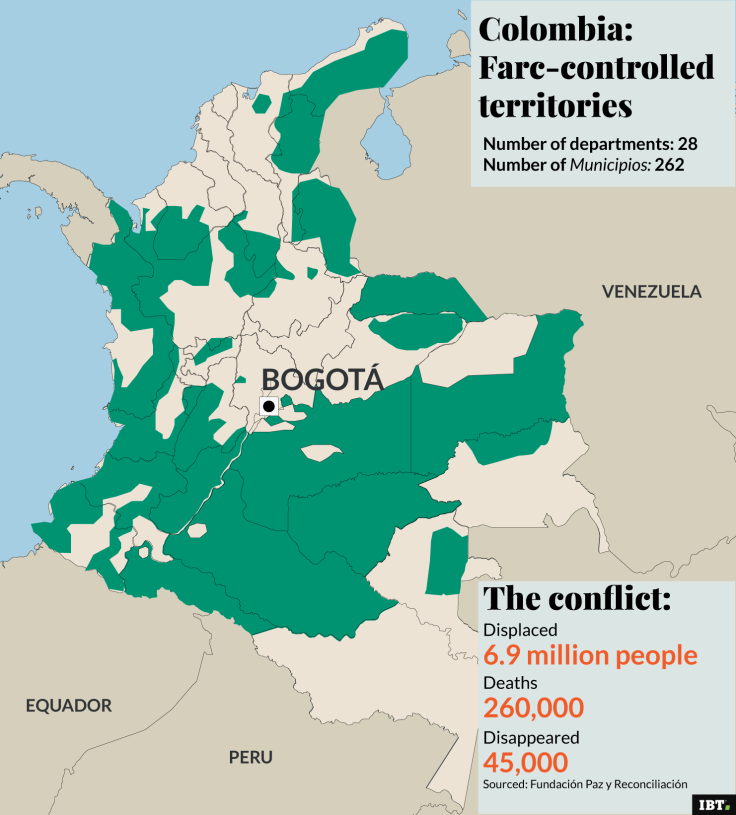

Uribe had galvanised millions of Colombians against the landmark agreement by arguing that Colombia could get a better deal, playing on resentment about a rebel group that is accused of widespread atrocities and war crimes over the past 52 years it has fought with the Colombian state.

Many of those who had suffered at the hands of the rebels – who are heavily involved in the Colombian drug trade – could not stomach the thought of Farc competing in the 2018 and 2022 election in Colombia, along with a commitment not to jail fighters who were willing to admit their crimes.

But just like the victory of the Brexit campaign in Britain took many of its leaders by surprise – at least two of them have left front-bench politics since June 23 – so Colombia's victorious No movement will now have to work out what they meant by "a better deal" and how they will achieve it.

"This actually saddles them with a huge responsibility: they have been claiming that there is an option for a plan B and how they will have to come up with what that will look like," Herbolzheimer said.

A particular sticking point for Farc, the government and the Uribe-led opposition will be over criminal charges against Farc guerrillas accused of war crimes. Farc have said they are willing to have their fighters serve time in jail for crimes committed during war, but only if all other parties in the conflict are held up to the same scrutiny.

For Farc, that translates as criminal charges for members of the police and army implicated in atrocities as well as the politicians in power at the time – which include Alvaro Uribe, who led Colombia between 2002 and 2010. By voting No, many of the deal's most vocal opponents may find that scrutiny not only falls on the Marxist guerillas of Farc, but at their own doors.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.