Election 2015: What the Trident nuclear deterrent is and why it matters to UK security

Any talk about nuclear weapons is alarming, especially when in the context of who should be in charge of pressing the metaphorical Red Button should such a terrifyingly Pyrrhic scenario unfold.

But talk nuclear weapons we must because, amid government austerity and heightened European security concerns over the Russia-Ukraine crisis, they have become one of the central issues in the 2015 general election.

It's all about the Trident programme. Trident is the UK's current nuclear deterrent. It's expensive – the most costly part of the country's defence spending, in fact – and dangerous, but its proponents say it is necessary to national and international security.

In an emotive and personal attack on Ed Miliband, Conservative defence secretary Michael Fallon wrote in The Times that the Labour party leader had "stabbed his own brother in the back" in the party's leadership election and was "willing to stab the UK in the back" over renewing Trident in order to do a deal with the anti-Trident Scottish National Party (SNP) and secure power in Westminster.

But the Labour party accused Fallon of smear tactics, adding it is in favour of Trident renewal to protect British national security.

What is Trident?

Trident operates a continuous at-sea nuclear deterrent. That means one of the programme's four nuclear submarines, which are based in the Faslane area of Scotland and operated by the Royal Navy, is always on patrol.

These Vanguard-class submarines are around 491ft in length, or over twice the size of two Boeing 747s, and powered by steam. A nuclear reactor inside the underwater vessels boils sea water, the steam from which is then used to propel them.

The four submarines – HMS Vanguard, HMS Vengeance, HMS Victorious and HMS Vigilant – are capable of carrying 16 Trident II D5 ballistic missiles, produced by the American arms manufacturer Lockheed Martin, each armed with up to eight nuclear warheads. As it stands, each submarine only carries three Trident missiles.

Their power and precision is stunning. Each missile is 44ft long, 83 inches in diameter, capable of exceeding speeds of over 13,000mph, and can hit targets up to 7,000 miles away, accurate to within a few feet.

The payload – or, just how powerful the destructive force of each warhead is – isn't known publicly. But, according to a parliamentary research paper, it is thought to be around 100 kilotons.

To put that in context, the atomic bomb Little Boy, dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima during the Second World War, had an energy yield of around 15 kilotons, killing as many as 80,000 people instantly. Therefore, a single warhead in a Trident II D5 missile has the destructive power equivalent to over six Hiroshimas at once.

The current fleet of submarines will come to the end of their working life in the 2030s. Because of the length of time it takes to build a new fleet, the issue of renewal is timely now and a decision must be made in 2016. The Trident missiles have already had their lives extended until the 2040s, when they will expire and be decommissioned.

But the cost of doing this – renewing and upgrading the nuclear deterrent infrastructure – is enormous. Estimates put the total cost, when the new submarine fleet comes into action in the 2030s, at £100bn ($147bn, €138bn). In 2013/14 alone, the NHS England budget was £95.6bn.

The government is committed to swingeing public spending cuts under its austerity programme to balance the Treasury's finances and clear the deficit. So with public finances under pressure, and public services being cut back, many are questioning why the government will spend billions on nuclear weapons.

Do we need a nuclear deterrent?

The nuclear deterrent is less about what is happening now and more about what could happen in the future. Who knows what the world will look like in 20 or 30 years? It is therefore better to stay secure by projecting the ultimate expression of military might – having an arsenal of ready-to-use nuclear weaponry – in order to make hostile states think twice before attacking.

It is, the argument goes, about creating a peaceful stalemate between nuclear powers known as "mutually-assured destruction", or the MAD doctrine. Why would one nuclear state attack another when it knows retaliation would be inevitable? You would have to be, well, mad.

This is why the "at-sea" deterrent in the Trident programme is seen as effective. If the mainland was ever attacked, the submarines are in a position to respond in kind. If the nuclear deterrent was land-based, it could easily be attacked and disabled, rendering retaliation impossible.

So at least one Trident-armed submarine is constantly patrolling the seas, though its location is always kept secret to bolster the effectiveness of the deterrent.

Given there has been a deterioration in the relations between Europe and Russia in light of the Ukraine crisis, talk of a renewed Cold War has left many saying now more than ever the UK must maintain a robust nuclear deterrent to assert its right to security and peace.

Also, being a nuclear power increases the UK's standing in the world, relative to its size, and means it has a seat at the top table with the likes of the US, China and Russia. Nuclear capability supposedly gives the UK more power and influence.

"Primarily, Trident is the ultimate guarantee of the UK's security," said Timothy Stafford, a research analyst at the Royal United Services Institute (Rusi).

"By having one submarine permanently deployed at sea, the capacity to retaliate to any nuclear attack from an adversary is maintained continuously, a bedrock principle of deterrence. In addition, the UK's nuclear weapons form part of its guarantee to Nato partners, something that discourages them from seeking weapons of their own.

"Although its counterintuitive, the UK's weapons thus contribute to its broader non-proliferation efforts."

But critics of the UK's nuclear deterrence argue that the weapons are fundamentally immoral because of the apocalyptic scale of deadly destruction they are capable of unleashing. What's more, there is the risk of a catastrophic accident should anything set the weapons off, such as a computer malfunction or human error. The risk of accident is low, but the potential cost is enormous.

They also argue that the UK should instead prioritise investment on things that materially improve people's lives, such as healthcare and education, especially in a time of government austerity.

The UK should lead by example and unilaterally disarm in the hope that others will follow, given most states are ostensibly committed to getting rid of nuclear weapons. Moreover, they say nuclear weapons are not befitting the needs of 21st century warfare. We should focus on both conventional and emerging defence areas, such as boosting soldier numbers and bolstering our cyber warfare capabilities.

"Senior military figures warn that the £100bn white elephant of Trident replacement does nothing to keep us safe – and is resulting in thousands of jobs in the armed forces being slashed," said Kate Hudson, general secretary of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND).

"How a blind commitment to squandering our overstretched national resources on a Cold War weapon can be touted as being 'strong on defence' is beyond me."

Rusi's Stafford said it is "often assumed that other aspects of defence policy will be strengthened" by scrapping Trident.

"However, given the political climate, the savings would likely be used to lessen the impact of austerity rather than to improve the armed forces," he said.

"The benefits of doing so would also be quite limited – while the headline figure of £100bn sounds vast, that figure is spread over the 30 year life of the program, meaning Trident equates to approximately 0.4% of annual UK government spending.

"Redistributing that money to public services or debt repayment would not have a transformative effect."

What are the parties saying?

The Conservatives are clear – they would modernise the Trident programme and invest in four new nuclear submarines, renewing the existing 24/7 at sea deterrent. Labour hold a similar view. The party wants to maintain the continuous deterrent, though they are open to cheaper ways of doing this, such as with only three submarines, if possible.

Liberal Democrats are different. The party does not prioritise having a continuous nuclear deterrent, instead suggesting that two submarines operating on a type of part-time system would be cheaper and more befitting the UK's modern security needs. Rather than constantly patrolling, submarines would be deployed as and when the threat to UK security warranted such action.

"This would keep Britain safe while allowing us to move down the nuclear ladder in a realistic and credible way," says the party.

"While we cannot predict the future, making this first move on the road to international nuclear disarmament is the right thing to do."

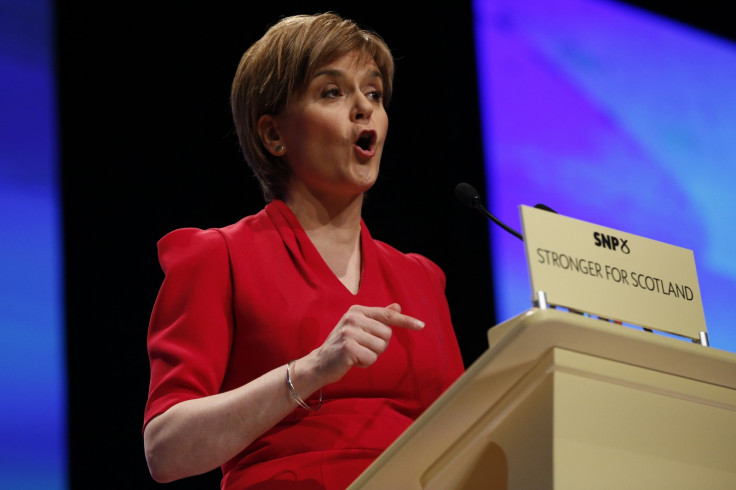

Both the SNP and the Green party see Trident as an abhorrence, in what it is capable of unleashing and the vast cost of renewing it. They are in favour of disarmament and spending the money elsewhere in government. Nicola Sturgeon, leader of the SNP, has marked opposition to Trident renewal as a "red line" in any deal to help Labour into Downing Street should there be a hung Parliament.

"Many of the compromises mentioned by the various parties have already been assessed," wrote Matthew Cottee, a research analyst on the Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Programme at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, on the Russian International Affairs Council website.

"In 2011 the Trident Alternatives Review (TAR) was commissioned to determine whether a like-for-like replacement of the existing weapon system was the best choice, or whether the UK could achieve a similar deterrent effect with different postures or equipment, and for less money.

"The TAR assessed a range of possibilities, from nuclear-capable aircraft to cruise missiles. Although it did not offer specific policy recommendations — nor did it consider unilateral disarmament — it suggested that the existing force structure provides relative value for money, should the UK wish to maintain CASD [continuous at-sea deterrence]."

This is a conclusion Stafford of Rusi agrees with.

"Reducing the number of submarines to less than four would most likely jeopardise the existing nuclear posture of continuous at-sea deterrence," he says.

"The other alternative would be to introduce a new system such as ground launched cruise missiles, or an airborne system. The drawback, as confirmed by the government's Trident Alternatives Review, is that winding down the old system and creating a new one would actually be even more expensive, due to the start-up costs."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.