Forced Adoption in the UK: Child Protection or 'Punishment Without a Crime'?

When a couple brought their newborn son to a hospital with a fractured arm, Coventry social services were called in on suspicion that the child might have been injured by his parents.

The mother was arrested, handcuffed and detained for nine hours, fearing her child might be taken away. Although not charged with any offence, the couple remain on police bail, preventing them leaving the country.

The child was taken by his Irish grandmother to Ireland, where is he supported by a family. Social services are still attempting to get an order through the courts for the grandmother to return to England.

This is just one case study of "forced adoption" – a term used by critics of the practice of removing children permanently from their parents and their subsequent adoption.

Aside from Croatia, Britain is the only EU member state that practices forced adoption and for some, it is a secretive system that allows social workers to separate children from loving families without proper justification and with little concern for their interests.

But for others, adoption is only carried out when it is in the child's best interests to do so – and criticism of the social care system is merely a consequence of the incomprehensibly difficult task of removing children from their parents.

There are 92,000 "looked after" children in the UK – meaning cared for by the state – according to NSPCC. More than half of these children in England and Wales became looked after because of abuse or neglect between 2012 and 2013 but critics say they have had their sons and daughters taken away for less.

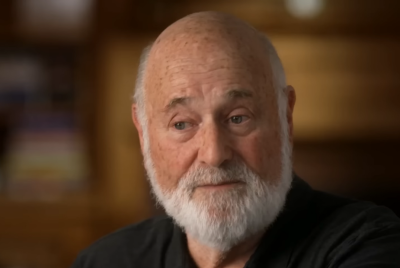

Ian Josephs, who runs the Forced Adoption website, has helped hundreds of families in this situation.

Speaking to IBTimes UK, he explained lots of parents feel they are punished without having committed a crime.

"No baby or child should be removed from parents and put into care unless one of the parents has committed, or at least been charged with a crime against children," he said.

But the argument for forcible adoptions is that if left too late, the child may be at risk or serious harm or even suffer death.

However, another problem lies in determining if and proving that, particularly in cases of emotional abuse, there is sufficient evidence to take the child away.

Critics state there are a number of procedural issues surrounding forced adoption. Some argue that due to increased funding for social services units – that effectively place a greater number of children with adopted families – there are financial incentives for local authorities to secure adoptions.

Moreover, some argue there is a demonisation of parent's embroiled in care proceedings. More than 90% of families where children are forcibly adopted live below the poverty line - despite counterarguments that child abuse and neglect are not class issues.

Around 45% of the parents have mental health problems, which often go undiagnosed, unassessed or untreated, before proceedings take place.

Once a child is placed for adoption, neither the parents nor child have any recourse open to them to reverse the process - even when evidence comes to light that shows that the reasons for the adoption were flawed.

Currently, families subjected to forced adoption may also be prohibited by court order from publicly discussing their case and attempting to contact their children.

"Most parents who contact me say they have done nothing wrong and if they speak the truth, they shouldn't be punished by the state by having their children confiscated – nor should they receive gagging orders to stop them complaining publicly and breaching their freedom of speech," said Josephs.

Speaking at a conference for the charity Children Screaming to be Heard, Josephs stated that when children are taken into care, gagging orders isolate children from family and friends.

"Even if parents have done committed a crime, the children haven't – we shouldn't treat them like them have," he added.

Introduced in April, the Children and Families Act 2014 seeks to reshape the adoption system – in particular, to get children placed with adoptive families more quickly.

But while adopting is necessary for children in danger, there are a number of solutions that don't punish the families of children who are not.

Such solutions include pre-proceedings intensive support, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) and specialist family support services.

Rather than bonuses for placing children in care, they could be used to support families remaining together.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.