How do shark teeth bite?

In a milestone study, researchers sought to find out exactly how shark teeth help the animal to kill.

Each of the more than 400 species of shark possesses a unique set of razor sharp teeth, all perfectly suited to ripping apart all types of prey, from marine mammals and seabirds, to turtles, and even humans on the odd occasion.

The shape of the teeth vary; some are simple triangles, while others are spear-shaped or serrated. Despite this variety though, scientists had thus far not detected any difference in how different shark teeth cut tissue.

Researchers from the University of Washington set out to understand why shark teeth are shaped differently, and what biological advantages various shapes have, by testing their performance under realistic conditions. Their findings were published in the journal Royal Society Open Science. The team believes the study was the first of its kind to mimic how sharks hunt and kill.

"When you have all these different tooth shapes, there should be some functional reason. That issue was fundamentally troubling to me," said senior author Adam Summers, a UW professor of biology and of aquatic and fishery sciences. "It seemed likely what we were missing is that sharks move when they eat."

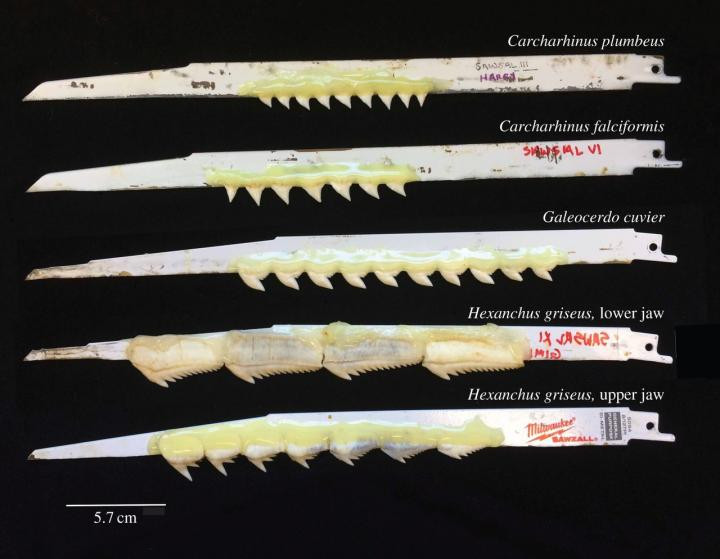

When sharks bite their prey they shake their heads rapidly, so evaluating how teeth perform in a side-to-side motion was crucial to the study tests. To do this the team fixed three very different kinds of shark teeth to the blade of a power saw, then cut through thick slices of Alaska chum salmon at a speed that mimicked the velocity of head-shaking as a shark devours its prey.

"Sure enough, when we cut through salmon, different teeth cut differently," Summers said. "We found a way to distinguish between these huge morphological differences that we see among shark teeth in nature."

They found that some types of teeth became blunt faster than others, including two kinds belonging to tiger and silky sharks, which lost their sharpness after only a few passes of the saw blade over the salmon. This led the researchers to think that these sharks must replace their teeth every time they kill their prey. On the other hand, teeth from the bluntnose sixgill shark did not become blunt as quickly but were not as effective at cutting either.

"There's this trade-off between sharpness and longevity of the tooth edge," Summers said. "It looks like some sharks must replace their teeth more often, giving them a consistently sharp tool."

This finding could lead to new insights about the feeding patterns of different sharks. For example, bluntnose sixgill sharks with blunter, more durable teeth might swallow their prey whole, whereas tiger sharks, which eat a larger range of prey, would bite it to pieces.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.