Landlords are under fire from a tax-hiking Treasury — but buy-to-let is far from dead

Higher stamp duty and an end to tax relief for mortgage interest costs; being a landlord is getting expense.

Tiny violins went out of stock shortly after Andrew Montlake, director at mortgage broker Coreco, told The Telegraph that an ongoing government crackdown on the landlord class would be "the beginning of the death of the middle class buy-to-let dream, which is a big shame".

Poor me, poor me, pour me another drink! Now the middle class buy-to-let dreamers face having to think about a different type of pension investment. It's hard to feel pity for buy-to-let investors, those with enough wealth to exploit the housing shortage for their own financial gain, while aspiring first-time buyers are shut out of the market because of high house prices. But is this really the death of the buy-to-let sector? And even if it is, should we be celebrating?

"No, because there will always be room for the private individual operator," said Alan Ward, chairman of the Residential Landlords Association (RLA). "There are lots of good reasons why they should be in there. But you will have to be even more savvy and aware of what you're doing.

"It's probably the end of the market for the 'accidental landlord'. The so-called casual person who protests that they're not really a landlord — the old insurance advert comes to mind, 'it's only the wife's old flat' — because you cannot take on the responsibilities of being a landlord without understanding what you are doing. And the pressure that we are now facing means that is even more the case."

He cited cheap mortgages and the ongoing need for rental properties as compelling reasons for people to still invest in buy-to-let. The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (Rics) estimates there will be a shortage of 1.8 million more rental homes by 2025. And to be fair, buy-to-let investors do help meet some of the demand for much-needed rental housing. They encourage more efficient use of the housing stock by carving up larger properties into a number of smaller units, or by using every bedroom of a home to increase their investment yield.

But there is a circular irony here: the growing need for more private rented property is partly driven by the fact fewer people can afford to buy their own homes, a problem not caused by affluent buy-to-let-investors, but one worsened by them and their voracious appetites for property, which depletes the already limited supply for aspiring homeowners and helps push prices higher.

That has been part of the motivation for the government's targeting of buy-to-let, which started in 2014 under the then chancellor, George Osborne, and has been continued by his successor Philip Hammond. It wants to increase homeownership and one way of trying to do this is to reduce demand in the market from buy-to-let investors, while eeking extra tax revenue from the remaining landlords. So what has the government done?

Tax hikes and letting fees ban

From April 2017, a blanket tax relief allowing landlords to offset their mortgage interest costs against their income tax bills is being progressively cut back, until 2021. Landlords argue they are being unfairly penalised and treated differently from other businesses, who are allowed to offset legitimate debt costs against their tax bills.

A blanket tax-free allowance for maintenance costs has also gone so landlords can only claim relief against work actually carried out, another dent to their incomes. In April 2016, the Treasury stuck an additional 3% rate on top of basic stamp duty rates for all purchases of extra property, meaning those which aren't intended to be the buyer's main residence. Now those looking to enter the buy-to-let sector, or expand an existing portfolio, face a significantly bigger stamp duty bill.

In his first Autumn Statement, Chancellor Philip Hammond said letting fees for tenants would be banned, with the burden of the costs transferred to landlords. There would be a consultation before legislation is brought to parliament, but the ban would come into force "as soon as possible", he said.

Enveloping all this is tighter lending rules for buy-to-let borrowers, driven by the Bank of England's concerns that the market is at risk of overheating while interest rates are at all-time lows. Banks must now subject borrowers to stricter affordability tests before a buy-to-let mortgage is approved, to make sure their customers can afford repayments in a number of different scenarios.

Also, landlord borrowers will have to show that their rents can cover a minimum 125% of their mortgage costs, with some lenders likely to demand a higher Income Coverage Ratio (ICR) because of tougher rules. The government has also just bolstered the Bank of England's regulatory powers over buy-to-let lenders — it will be able to set loan-to-value and ICR limits for individual institutions.

It is the end to mortgage interest relief that worries Ward in particular. He said he doesn't think the government understands "the storm" it will unleash by 2021, when the cuts are fully realised. "People are telling me already they are being pushed into a higher tax bracket even if they've only got one property because it is taxing them on the income and not the profit, and that is a very, very dangerous precedent to have set," he said.

Ward said there are many good long-term landlords with stable tenant relations providing lots of decent homes for rent, whose operations are undermined, perhaps fatally, by the increase in their costs.

"Why destabilise good businesses like that?" he said. "It always comes back to the pressure on rents in the marketplace... But the market can't always sustain that. It may very well sustain that in a buoyant market like London or the south east. But that only makes it worse for the people who are living there, because so much policy is predicated on the London experience, but it doesn't apply almost anywhere else in the country."

He said there are many areas of the country where rents have not risen substantially for several years, particularly if there are affordability concerns, giving landlords little or no room to offset their costs with higher rents — meaning many may have to sell up.

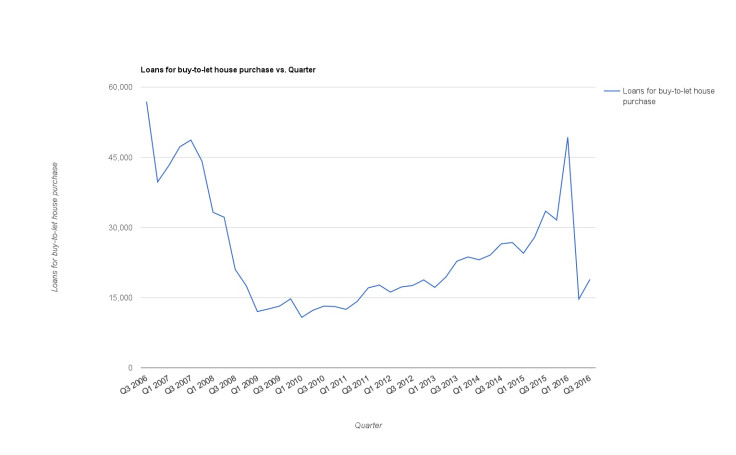

Despite all the changes, buy-to-let demand doesn't appear to have slowed all that much. Data from the Council of Mortgage Lenders (CML) showed that there were still 18,900 buy-to-let mortgages for house purchase approved in the third quarter of 2016, up 30% on the previous quarter.

But the second quarter was gripped by Brexit uncertainty, and demand had spiked hugely in the month's first quarter — ahead of the stamp duty hike in April — to 49,300 buy-to-let loans, a nine and a half year high. Those who may have purchased later in the year, spreading demand, brought forward investment decisions to beat the stamp duty deadline. Looking at the figures with this in mind, demand is pretty stable — buy-to-let's heart monitor is still beeping.

It remains to be seen whether the ending of relief for mortgage interest rate costs will be the blow that kills it. But the fact that people are still investing with the full knowledge of this change suggests there are many landlords willing and able to cope with it, even if they don't like it. Buy-to-let may be down, but it's not out.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.