Malaysia Airlines MH370: Ocean Currents Could Spread Debris 'Several Hundred Miles' from Search Site

Debris from Malaysia Airlines flight MH370 may be impossible to find due to strong ocean currents in the southern Indian Ocean, making a difficult search even harder.

Apart from adverse weather conditions, which have hindered recent efforts to recover the missing Boeing 777, the wreckage of the aircraft may have been dispersed and pushed in different directions at different speeds.

The current search zone is around 2,500km from Perth on the western Australian coast. According to Thai officials, its satellite images show 300 floating objects in the area, around 2,700km west of Perth.

Professor Chris Hughes, of the UK's National Oceanography Centre, said it would be difficult to find a more complicated region of the ocean to be searching for the plane's debris.

Ocean currents

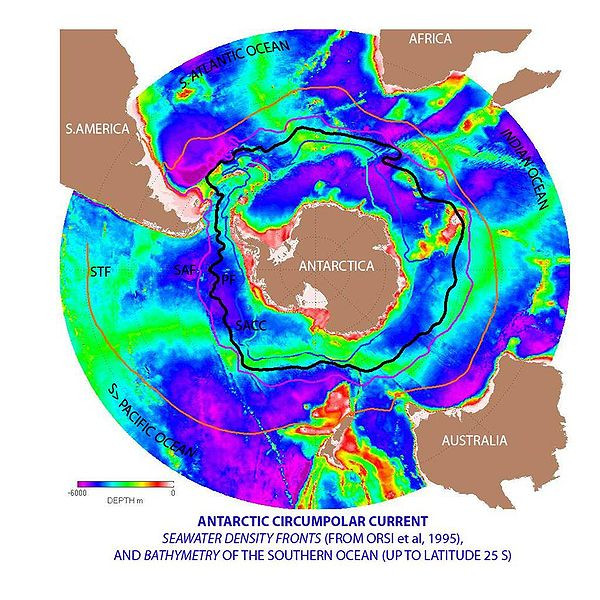

Writing on The Conversation website, Hughes said the search zone lies just on the northern flank of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, an ocean current that flows clockwise from east to west around Antarctica.

The ACC, otherwise known as a West Wind Drift, is the dominant circulation feature of the Southern Ocean and is the largest ocean current. Hughes said the effect of the earth's rotation leads to the eastwards-flowing currents focusing into narrow bands, like rivers flowing within the ocean.

He said: "The currents loop into closed 'eddies' that break away from their current and spin off, like high and low pressure systems moving through the atmosphere."

"Unlike the atmosphere, these highs and lows are on a much smaller scale, perhaps 100 to 500km across. Typical flow speeds are around 20cm per second - about ten miles per day - but faster speeds of up to 100cm per second are possible, and the direction of flow at any one time is very unpredictable."

Hughes added that such conditions would make searching for the debris extremely difficult: "The search area spans both the northernmost river of the Circumpolar Current, and a much calmer area to the north where currents are much slower. This means debris could have been scattered and pulled in different directions, at different speeds."

Wind

The wind may further complicate the process. According to Hughes, it will be pushed by the wind but surrounded by water in the Ekman layer, which is the top 50m of the ocean in which the effect of the wind is felt.

Since the plane was lost over two weeks ago, the debris may have drifted several hundred miles from where the plane is presumed to have crashed. And even if the debris spotted is confirmed to be from the missing airliner, the challenge of finding sunken wreckage remains.

Hughes said: "If the debris is confirmed to be from the Malaysia Airlines plane, a lot of work will remain to be done. It will still be a long time before we are in a position to determine what happened to flight MH370."

He added that the depth of the ocean, around 3,500m to 4,000m, will involve combing a vast area with advanced sonar imaging technology.

Hughes concluded: "Then there is the challenge of reaching it: only specialised equipment can operate at the pressures of more than 350 atmospheres present at such depths, although from that point of view it could have been worse — large areas of the sea floor lie more than 5,000 metres below the surface, with a few narrow trenches beyond 10,000 metres deep."

Force of impact

Depending on its final cruising altitude, the impact of the crash may have broken the debris into minute, undetectable pieces, rendering the search efforts impossible.

Although some have suggested the plane may have glided to its final destination, a more violent crash with a large impact force would have destroyed the structural intergrity of the plane.

The remote location site, along with the rugged underwater terrain, would have broken the aircraft into many pieces too small to recover.

Robin Beaman, an underwater geologist from the James Cook University in Australia, said submerged volcanoes will make the search much more difficult because of the changing landscape beneath the southern Indian Ocean.

He told the Sydney Morning Herald: "It's very unfortunate if that debris has landed on the active crest area, it will make life more challenging. It's rugged, it's covered in faults, fine-scale gullies and ridges, there isn't a lot of sediment blanketing that part of the world because it's fresh [in geological terms]."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.