The Passion of Jerome Kerviel: From Rogue Trader to Popish Pilgrim

Before sacrificing himself to the authorities, Jerome Kerviel went for one last supper with friends, though it's not clear if there were twelve of them.

After months of preaching against the financial sector, a modern-day Rome whose empire of wealth, power and debauchery spans the globe, Kerviel's original sin had finally caught up with him.

A former Societe Generale trader, Kerviel was convicted in 2010 by the French courts of going rogue after his fraudulent activities cost the investment bank €4.9bn (£4bn, $6.7bn).

He was sentenced to three years in prison (five if you include the two suspended years) and ordered to repay the unholy sum of money, lost in a €50bn series of unauthorised trades.

But his appeal against the conviction – on the grounds that the bank's systems allowed him to make such trades as long as they were profitable – had held up his punishment.

That is until the courts dismissed Kerviel's appeal against the jail sentence in March 2014, though they also said he would not have to repay the billions SocGen lost under his trading. A new amount will be decided in a separate civil case.

While his appeal was being heard in Paris, Kerviel was embarking on a penitential pilgrimage from Rome, where he had met Pope Francis, to the French capital.

Outside the Vatican, the Holy See and the rogue trader discussed the "tyranny of the markets". Before Kerviel set about his epic 900 mile walk, the Catholic leader - God's own representative on earth and third in command under Jesus – blessed Kerviel's rosary beads.

"It was incredible to meet the Pope," Kerviel told the Financial Times after the meeting.

"My mind was closed, and he found the key to open it and let the light in. It is difficult to put words to it."

When he lost his appeal, Kerviel continued his contemplative protest march against the markets.

But he made sure he kept within the Italian border, because one foot stepped into France would mean his incarceration.

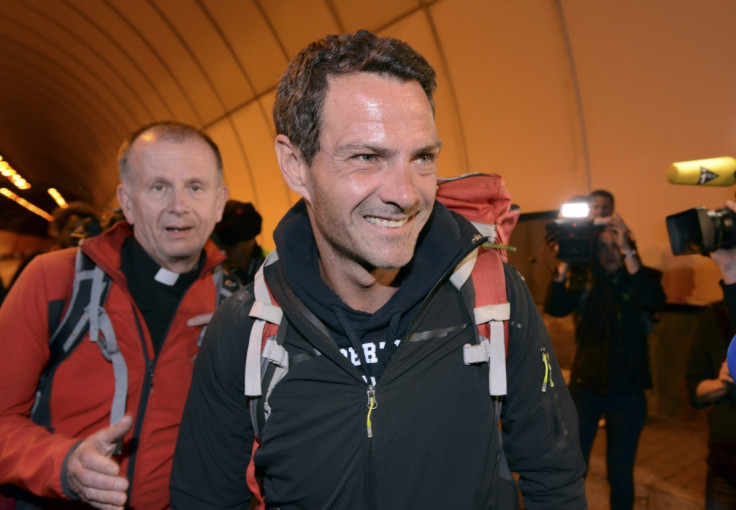

French authorities warned that if he didn't come back to the country he would be hunted down as a fugitive of justice. So he crossed the border, escorted by the Catholic priest Father Patrice Gourrier, and handed himself in.

Kerviel doesn't dispute the unauthorised trades, but instead claims he is being held solely responsible for a failure of the bank's compliance controls.

This is an area SocGen has since ploughed hundreds of millions of pounds into improving after Kerviel's trades brought the bank to its knees. It had €4m extracted by regulators because of lax controls.

He also claims his seniors knew about his trades and that no independent assessment has been made of the Societe Generale losses attributed to him.

"No legal expert has ever validated Societe Generale's alleged losses," said David Koubbi, Kerviel's lawyer, at Kerviel's appeal launch in June 2013.

Kerviel had risen up the ranks at SocGen, starting in the middle office before becoming a trader. He made hundreds of millions of euros for the bank by manipulating the SocGen system, allowing him to make unauthorised trades above the limits allowed.

It worked for a while, but then he became too confident in his own ability. The pride before a fall, a biblical lesson he learned on the trading floor of real life.

Kerviel made enormous bets that stock markets would rise again in 2008, just as the financial crisis was taking hold. But stocks didn't rise and the global economy entered a depression. The rest, as they say in France, est l'histoire.

Now saintly Kerviel will languish in a prison cell, clutching his blessed rosary beads, repaying his debt to society – even if he can't repay what he owes the bank.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.