Thanksgiving Day 2017 or celebration of genocide: Why is the American holiday a controversial one?

This year, the annual holiday falls on 23 November and will be celebrated extensively across the US and Canada.

Thanksgiving Day is less than two weeks away (23 November) and while most families across North America are busy writing up their shopping lists and asking Google for the quickest ways to cook a turkey, a number of people are preparing once again to protest the holiday.

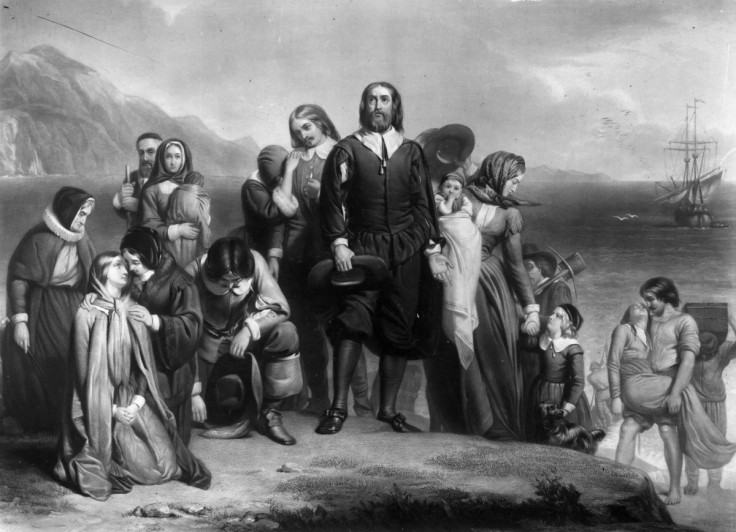

The general theory is that the festivities originated in 1621, when the Wampanoag Native Americans shared a harvest with the Plymouth colonists who had spent the previous year facing severe famine. The Pilgrims, who had crossed the Atlantic Ocean from Britain, to try their luck in the New World, were unfamiliar with the terrain and needed help learning how to grown corn and how to fish.

Thanksgiving is meant to celebrate the bond that the early settlers shared with the natives but for many members of the continent's indigenous community, it is a day that marks the genocide the aboriginals suffered at the hands of the colonists who are said to have murdered and enslaved them, stole their lands and forced them to leave their homes and go into hiding.

A number of groups like the United American Indians of New England opt instead to mark the day as National Day of Mourning to remember the brutalities faced by the native American community. "It is a day of remembrance and spiritual connection as well as a protest of the racism and oppression which Native Americans continue to experience," the organisation mentions in its official statement.

Since 1970, protesters have taken to gathering at the top of Cole's Hill, which overlooks Plymouth Rock, to commemorate a National Day of Mourning, with similar events being held around the country.

Suzan Shown Harjo is a member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes and has been working as an activist and voice for the Native American people. In a 2014 interview with The Takeaway she explained that despite being whitewashed by the settlers, Thanksgiving is quintessentially Native American.

"There's so much mythology that's been built up by the Pilgrim's side, that I don't think we can sort through it," she said at the time.

"And on the Natives side there's so much anger. I don't know if there's a midpoint between mourning and giving thanks, but giving thanks is a genuine native tradition and should be celebrated with a feast of solely native foods."

Like her, many other activists are not opposed to the idea of a day to give thanks, but feel that the true story of the Native American struggle has been replaced by turkey and cranberry sauce. There is concern, especially, that children are taught a distorted history of events.

"We're certainly not against giving thanks. As indigenous people we give thanks every day," Mahtowin Munro, co-leader of the United American Indians of New England told the Final Call in October. "The issue here with the Thanksgiving holiday as celebrated in the United States is that it perpetuates this myth that the wonderful Pilgrims came here from Europe and were so kind and good to the Native people who were here and lived happily ever after."

"What happened is not just some harmless lie that can be overlooked with a wink and a smile," Mark Anquoe, of the International Indian Treaty Council and American Indian Movement added. "The modern practice of Thanksgiving makes mockery of our people and that affects children's self-esteem and emotional growth. Native children have some of the highest suicide rates in the country and that's part of it."

Author Sherman Alexie, who is from the Spokane and Coeur d'Alene tribes, offered a lighter take on the subject of the celebration. "We live up to the spirit of Thanksgiving [because] we invite all of our most desperately lonely white [friends] to come eat with us. We always end up with the recently broken up, the recently divorced, the broken-hearted," he told Sadie Magazine. "From the very beginning, Indians have been taking care of broken-hearted white people. We just extend that tradition."