World first 3D-printed jet engines created by Australian engineers

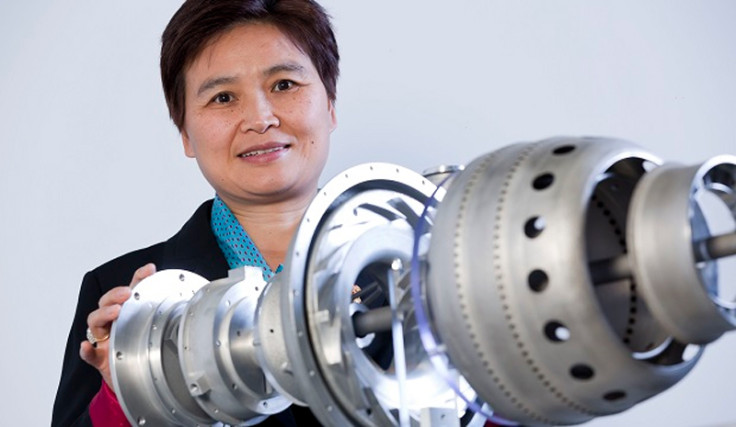

Engineers from Monash University in Australia have succeeded in creating the world's first 3D-printed jet engines – a breakthrough that could drastically reduce the time taken to manufacture aircraft.

At the moment, building and assembling the components of a jet engine can take about two years.

Working together with Deakin University and the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), the researchers managed to print two complete full-sized auxiliary power units, and each one took only about a month, although the whole project took a year.

The gas turbine engine chosen to be 3D-printed was a small auxiliary power unit provided by French aircraft and rocket engine manufacturer Safran. It is used to power slightly older aircraft like the business jet Dassault Falcon 20.

Since the engine is an old design with no computerised drawings, the researchers took the engine apart and 3D-scanned each component so that they could analyse how the final product would fit together.

Then they printed out two units consisting of 14 major components using the Concept Laser's X line 1000R 3D printer – the world's biggest laser metal melting 3D printer that enables tool-less manufacturing of large components and has a huge build space of 630mm x 400mm x 500mm.

"It was our chance to prove what we could do," says Professor Xinhua Wu, the director of the Monash Centre for Additive Manufacturing, who has 25 years' experience in the aerospace industry.

"But when we reviewed the plans we realised that the engine had evolved over years of manufacture. So we took the engine to pieces and scanned the components. Then we printed two copies."

The 3D-printed jet engine project was supported by the Australian government, and numerous aerospace companies are now forming partnerships with Monash University.

The next step for the researchers will be to stress-test each component in a real-world situation, and this will take up to two years, the required timespan to ensure the parts are as safe as traditionally-produced components.

"The project is a spectacular proof of concept that's leading to significant contracts with aerospace companies. It was a challenge for the team and pushed the technology to new heights of success – no one has printed an entire engine commercially yet, "said Ben Batagol, of Amaero Engineering, the company created by Monash University to make the technology available to Australian industry.

A huge number of applications for 3D printing are appearing now – from 3D-printed houses made from recycled building materials, to 3D-printed medical implants, 3D-printed electric cars, and even 3D-printed fashion.

The aerospace industry has a huge interest in additive manufacturing (the real name for 3D printing) as the technology can produce super-strong components in a fraction of the time that they take today.

But the materials used don't have to be metal – plastic works pretty well too and is now starting to be used frequently in the aerospace industry for accessories and fixtures in aircraft cabins.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.