World's largest fish traced by environmental DNA

Testing DNA from the sharks' environment is less invasive than traditional tissue sampling and could aid conservation efforts.

DNA floating in the sea can give researchers crucial information for tracking whale shark populations, a new study shows.

Getting DNA samples from rare animals such as whale sharks is hard, and learning about the DNA of this rare and elusive species has been historically tricky. Now researchers show, in a paper published in Nature Ecology and Evolution, that they can get a good estimate of a whale shark population's genetic makeup just from sampling seawater near the sharks.

This is the first time that environmental DNA – or eDNA – has been directly compared with tissue samples to compare sequence information.

Exactly where in the sharks this DNA comes from, the study authors aren't yet sure. "We highly suspect it comes from urine and faeces. Of course it could also come from the skin," study author Eva Egelyng Sigsgaard of the Natural History Museum of Denmark, told IBTimes UK.

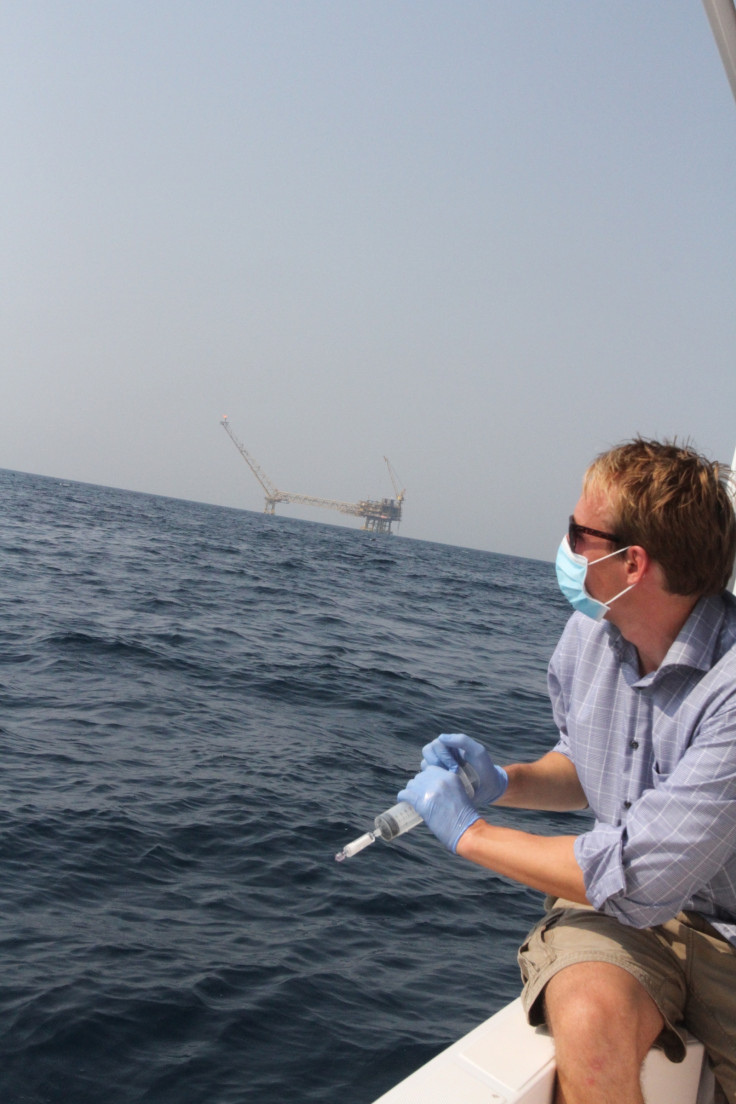

Egelyng Sigsgaard and her colleagues sampled water nearby a school of whale sharks while they were feeding at the Al Shaheen oil field near Qatar in the Arabian Gulf. They compared the eDNA they collected from seawater with traditional tissue samples.

They used high-throughput sequencing and DNA amplification to study DNA from the mitochondria, the powerhouses of the cells. They looked at mitochondrial DNA specifically – rather than the DNA found in the main genome – because there was more of it about in the seawater samples, Egelyng Sigsgaard says.

The researchers found that seawater nearby the sharks could tell them crucial information about population size both locally and across the entire Indo-Pacific Ocean.

The seawater samples had to be taken from quite close by to the sharks, Sigsgaard says. "We did try to take samples further away from the sharks but it was the ones taken from inside the group where they were feeding that worked well."

Gary Carvalho, molecular ecologist at Bangor University in the UK, says that the study is significant for showing that it is possible to use eDNA from seawater to estimate genetic diversity, measure population sizes and compare one whale shark population to another.

He went on to say: "eDNA is a relatively new approach for sampling genetic material from the environment, without a need to collect individuals themselves," he says. Taking the samples from close to the sharks is much less invasive than taking tissue samples or tagging, and points to easier ways to get genetic information to inform conservation efforts.

"Importantly, the data can be used to identify genetically distinct populations that may be specifically adapted to local conditions, thereby requiring application of strict conservation measures," he added.

The whale shark is endangered primarily due to human exploitation for meat, fins and oil. Until now, population studies of whale sharks have primarily depended on tissue sampling and tagging, which are expensive for researchers and can potentially harm the sharks, the authors write in the paper.

If researchers and conservationists could rely on eDNA instead it could benefit both sharks and scientists. Next they plan to use the technique to look at nuclear DNA as well as mitochondrial DNA, and to fine-tune the method to learn more about the individual sharks within the group, says Egelyng Sigsgaard.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.