Zero-Hour Contracts: The Rise of a Labour Market Phenomenon

Zero-hour contracts are not a new phenomenon. In 1993, Angel Eagle MP asked the then Secretary of State for Employment David Hunt if he was aware of an "increasing prevalence" of zero-hour contracts. According to Eagle, an individual is given a contract of employment with zero-hours to fulfil and is "then expected to be on the end of a telephone, to be called in at the whim of the employer- not knowing from one day to the next how many hours they will be expected to work".

Hunt's reply was sharp. He contested: "The honourable lady will not succeed in trying to portray a different picture from the one that is reality: that a greater proportion of the working age population are in work in the UK than in most other countries in the rest of Europe."

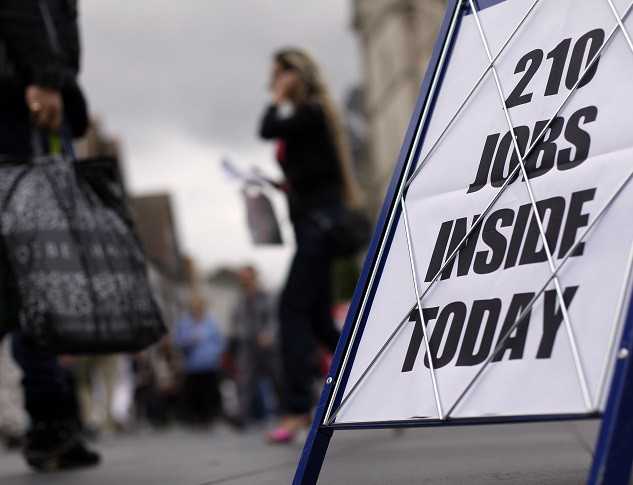

However, the number of zero-hours contracts has risen sharply in recent years. According to the Office for National Statistics, the number of people employed on zero-hours contracts rose from 134,000 in 2006 (0.5% of the workforce) to 208,000 (0.7%) in 2012. The jump in popularity has inflamed the imaginations of politicians and the public alike.

For some, the contacts are exploitative. They take advantage of the unemployed and plump up the government's employment figures with poorly paid work. As Ian Binley, of the Work Foundation, says "zero-hour contracts have come to symbolise a wider concern that the labour market is moving towards more contingent, less secure, and more exploitative forms of employment at a time when in many areas jobs are scarce and people have little choice over taking whatever work is available".

For others, the employment agreements offer much needed flexibility - especially when Britain is tentatively recovering from the worse global recession since World War II. The Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, the organisation for HR professionals, has even claimed the controversial contracts have been "unfairly demonised" and "oversimplified". But what exactly is a zero-hour contract?

No Such Thing

There is no such thing as a zero-hour contract. Well, there is no set form nor defined legal term of the fabled employment agreement. Typically, a zero-hour contract means an employer is not obliged to provide a minimum amount of work for an employee, but the worker - at least in some instances - is obliged to be available for work.

But under other so-called zero-hour contracts, it may be perfectly legitimate for an employee to turn work down. It is no surprise then, with these bamboozling definitions in mind, it is very difficult to estimate how many workers in the UK are on such agreements.

In fact, three and a half vastly different estimations have been published. The ONS, for example, initially claimed that 200,000 people were on the flexible contracts. But after a review of the research methodology used, the organisation increased its figure by a staggering 25%. The ONS concluded 250,000 workers in Britain were on zero-hour contracts.

Days after the ONS had revised its figure, a new estimate was published. The CIPD had ran its own sums. The organisation claimed the ONS may have underestimated the number of workers on the controversial contracts.

The ONS were not out just by a few hundred, not even a few thousand, but the research body could have underestimated the number of employees on the flexible contracts by a colossal 750,000. The actual number of workers in the UK on zero-hour contracts, according to the CIPD, is more than one million.

But just more than a month after the CIPD released its data, the trade union Unite published its findings. Again, the new figure implied the old estimates had got the number of people on zero-hour contracts spectacularly wrong. Unite claimed as many as five and a half million workers in the country were on the deals offering little guaranteed work.

Because there is no legal term for zero-hour contracts, it seems very hard to estimate how many people are on them. But what type of employers would want to use such an agreement?

Hotel and Restaurants

The employment agreements allow businesses to hire staff, while being able to easily adapt to change. The contracts can also be used to increase services and enable employers to keep hold of workers who want less hours. It is no surprise, therefore, that the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills estimates public services and the distribution, accommodation and food services sector lead the field in employing workers on zero-hour contracts.

In addition, the Workplace Employment Relations Study found that the largest increase in the proportion of workplaces using zero-hour contracts between 2004 and 2011 was in the hotel and restaurant sector.

But despite people's preconceptions of little work and low-pay, the available evidence suggests that zero-hour contracts are used by individuals with varying income distributions. The Labour Force Survey, for example, suggests that around 31% of those on zero-hours contracts in Q4 2012 worked in elementary occupations – including construction and cleaning – and around 20% on the controversial agreements worked in professional or technical occupations.

However, the LFS also revealed something worrying. It showed that the actual hours worked by employees on zero-hour contracts has declined from more than 30 hours per week in 2000 to between 21 and 25 hours in 2013 – that means up to nine hours of work a week have been lost.

Furthermore, research by CIPD suggests that some of the workers on the employment agreements are poorly treated. The organisation's research revealed two out of five workers on the contracts said they had been informed only hours before starting work that a shift had been cancelled. In addition, the two in 10 (20%) of workers on the contracts are sometimes or always docked wages or penalised in some way if they are not available for work.

Case Study: Rebecca, a social care worker based in Wales

Rebecca works for a private company supporting young adults with complex care needs. She is on a zero-hour contract and her hours vary enormously. For example, one week she worked 28.45 hours, and then the next she clocked-up 56 hours. Rebecca says the amount of hours she will work is a surprise every week.

But the families of the people Rebecca and her colleagues support do not understand why they are on a zero-hour contracts. This is because the clients' care needs will not decrease – they will only ever increase.

With constantly varying hours, Rebecca explains she cannot budget. She and her family are in social housing, she can claim housing and council tax benefits. But Rebecca would prefer regular hours so she can arrange appropriate childcare.

At the moment her partner is unable to work as he cannot commit to set hours. Rebecca wants the government to make companies offer a minimum of 16 hours per week for employees on zero-hour contracts unless workers ask for less in writing.

Solutions, Solutions, Solutions

The upsurge in interest of the agreements has led the Business Secretary Vince Cable to say the government may introduce a ban on exclusivity clauses in zero-hour contracts, which stop people from working for other firms. This would certainly make the agreements between employees and employers less asymmetrical and unfair.

But opposition still remains against the contracts. After Cable's announcement, Frances O'Grady, general secretary of trade union organisation the Trades Union Congress, claimed the employment agreements spread fear throughout the job market and are "one of the reasons why so many hard-working people are struggling to make ends meet, in spite of the recovery."

However, despite O'Grady's protests it looks like zero-hour contracts are here to stay. The current government has ruled out banning them, and the Labour Party has merely promised "action" into zero-hour contracts, but has not pledge it would eliminate them. Until the politicians do pass any legislation, perhaps employees can take advantage of the employment agreements.

As Ivor Adair, an associate in Slater & Gordon's employment team, notes. Many of the agreements are "poorly drafted" and although "some contain post-termination restrictions (for example on your ability to compete), which are entirely inappropriate" employees should not be scared. The contracts can be changed before a worker signs on the dotted line. Sometimes it is worth bargaining with an employer to secure a more preferable agreement.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.