Anthropocene: The 208 crystals that don't exist anywhere else in the universe

Humans have inadvertently created hundreds of new minerals. As we aren't anywhere else in the universe, they probably aren't either.

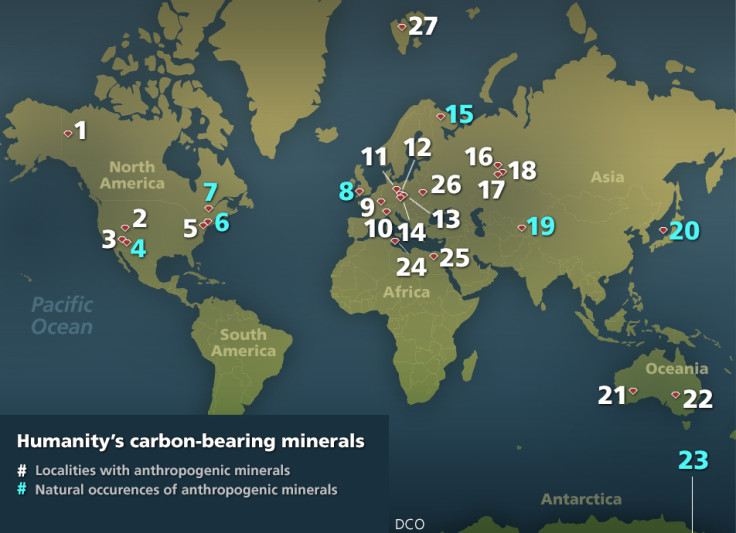

Nothing has changed the planet's minerals more than humans since the origin of oxygen on Earth more than 2.2 billion years ago. Humans have created more than 200 new minerals, mostly in the past few decades. This is strong evidence that we have entered the Anthropocene epoch, a new geological era, scientists argue.

These "Anthropocene minerals" don't include the vast majority of crystalline compounds that we have made on purpose, such as yttrium aluminum garnet crystals for use in laser technologies, or crystalline building materials used in concrete and bricks. The Anthropocene minerals are mostly compounds made by accident as a result of human activity.

The authors of a study listing these new minerals, published in the journal American Mineralogist, argue that they add to the evidence that we have entered the Anthropocene.

The 208 anthropogenic minerals were mostly created in the past few decades, study author Ed Grew of the University of Maine told IBTimes UK. This is the first time they have been collected together as evidence for the onset of the Anthropocene.

"I had no preconceived notion of the minerals that might be found. I must admit that seeing it all now it seems like an unusually large number, much more than I would have expected than before embarking."

Scratching the surface

How are Anthropocene minerals classified?

First, the substance has to have a chemical and physical structure unlike that of any other officially recognised crystal.

Second, if it was recognised by the International Mineralogical Association after 1995 then it also can't have been made on purpose by humans. Before this period, several minerals that were created specifically for use in technologies were included. These are called 'grandfather' minerals.

The number of anthropogenic minerals – those mostly formed indirectly by human activity – is dwarfed next to the total number of unique crystal substances made by humans. These number more than 180,000 – about 36 times the number of naturally occurring minerals.

"We thought humans might have doubled the number of minerals at the Earth's surface," said Jan Zalasiewicz, who reviewed an early version of the paper but did not carry out the research. Zalasiewicz convenes the Anthropocene Working Group, which is weighing up the evidence of whether we have or haven't entered a new geological epoch for the International Union of Geological Sciences.

"We've gone from about 5,000 natural minerals, most vanishingly rare, up to more than 180,000 – that is a huge change in mineral diversity. Most of that will have happened over last century or few decades."

The authors of the list of 208 minerals revisit a question raised by Zalasiewicz in 2013: What traces will humans leave in the Earth's geology in tens of millions of years for a future observer to discover and use to deduce what happened in this epoch? And will it really seem different enough from the previous epoch, the Holocene, to be considered a fundamentally

distinct era?

Study author Robert Hazen of the Carnegie Institute for Science in the US and his colleagues put forward three possible clues for a future observer: the hundreds of new minerals formed as an indirect product of human activity, the large-scale shifting of rock for mining and building, and the redistribution of minerals that have a particular value for humans, such as precious stones.

Mine minerals

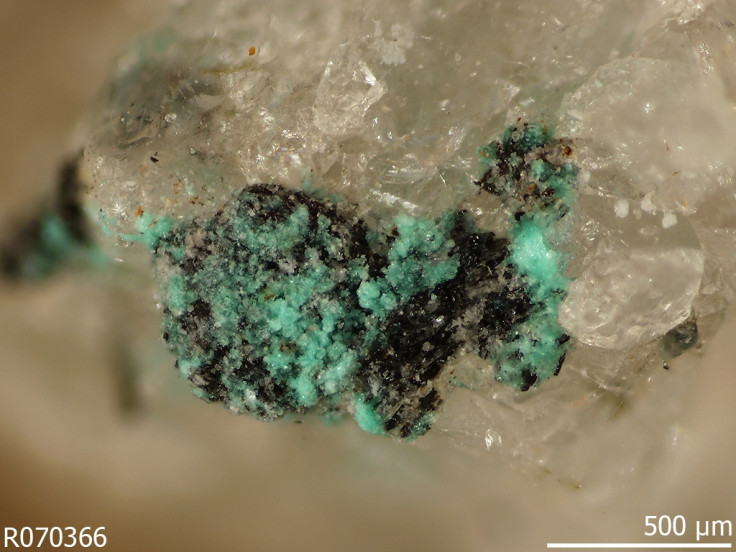

Many of the Anthropocene minerals are found in or near mines. Some grow in ore dumps, such as wheatleyite and widgiemoolthalite. Some are found in mine tunnel walls, like albrechtschraufite, canavesite, ježekite and línekite. Others are associated with mine dump fires, like acetamide, hoelite and kladnoite.

Some have absolutely nothing to do with mines. The Anthropocene mineral calclacite is only found in museum storage cabinets, and probably nowhere else on Earth. It was first discovered in the Royal Museum of Natural History in Brussels, Belgium.

Minerals of the Anthropocene

Two hundred and eight might not sound like an enormous number – but it's 4% of the now 5,200 or so officially recognised minerals that exist on Earth in total.

They include the yellow, orange and green crystals of the mineral Andersonite, found in abandoned uranium mines in the south-west US and thought not to occur otherwise in nature. Others such as wheatleyite are found in ore dumps by mines. The mineral calclacite has only been found to grow in old museum cabinets and nowhere else

in nature.

"Given humanity's pervasive influences on the environment, there must be hundreds of as yet unrecognised 'minerals' in old mines, smelters, abandoned buildings, and other sites," said Robert Downs of the University of Arizona, also a study author, in a statement.

"Meanwhile, new suites of compounds may now be forming in, for example, solid waste dumps where old batteries, electronics, appliances, and other high-tech discards are exposed to weathering and alteration."

Other minerals that do occur naturally but not in large quantities have also made it on to the list. They included minerals discovered in places such as a Tunisian shipwreck, on bronze Egyptian artefacts and at prehistoric sacrificial burning sites in Austria.

These minerals are of interest as they could push back the start date of the Anthropocene, if it is acknowledged. Instead of beginning with the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century, it could be pushed back as far as the Bronze Age.

Shifting rock and collecting stones

But the Anthropocene is not just about the number of new minerals we've created, on purpose or by accident. It's also about how we've transformed landscapes at surface level and underground through activities like mining and building cities and roads.

"Mining operations have stripped the near-surface environment of ores and fossil fuels, leaving large open pits, tunnel complexes, and, in the case of strip mining, sheared-off mountaintops," Hazen writes in the paper.

As well as blasting aside rock when it's in our way, humans' fascination with rocks is another tell-tale sign that would mark out the Anthropocene to an observer millions of years in the future.

"From modest beginner sets of more common minerals to the world's greatest museums, these collections, if buried in the stratigraphic record and subsequently unearthed in the distant future, would reveal unambiguously the passion of our species for the beauty and wonder of the mineral kingdom," Hazen writes.

An explosion of species

The Anthropocene is usually associated with destruction caused by humans, such as massive losses in biodiversity, increasing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and loss of sea ice. But the changes in the Earth's mineralogy is something to celebrate, argues Peter Heaney of Penn State University in an editorial in the same issue of American Mineralogist.

"Most people regard the Anthropocene as an epoch in which Earth's diversity has been catastrophically diminished and homogenised at the hands of humanity," Heaney writes.

"From a materials perspective, however, the Anthropocene is an era of unparalleled diversification. As I write this review, the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database lists 187,093 crystal structures, and that number increases weekly. These include compounds that never before existed on Earth, in the Solar System, maybe in the universe, and they were created by human ingenuity."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.