Auschwitz liberation 70th anniversary: Monowitz, the forgotten camp

Holocaust Memorial Day 2015 marks the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest Nazi death camp

The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum is one of the most frequently visited places in Poland, with over a million tourists visiting the industrial town of Oswiecim to witness one of the darkest periods in human history. For most, the "Arbeit Mach Frei" sign at the entrance to Auschwitz I or the train platform at Birkenau stand as potent symbols of the suffering millions endured at the camp. But the third main camp, Monowitz – or Auschwitz III – is lesser known.

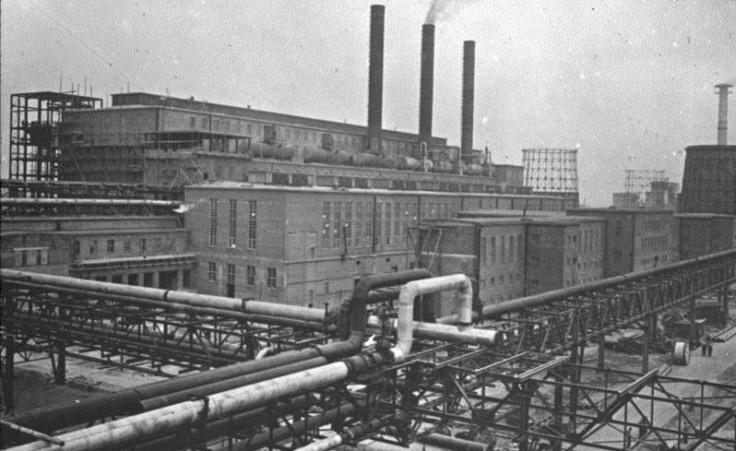

Aside from a few concrete posts and the former bunkers of the SS guards, nothing remains of Monowitz. Constructed as a workcamp in 1942 to provide slave labour for the German chemical company IG Farben, the prisoner population of the camp at its peak was around 12,000. Yet in 2015, no evidence of the camp remains. It was dismantled following the Soviet liberation of the Auschwitz complex in 1945, and now two modern Polish manufacturing companies stand on the site.

"I would argue that Monowitz, or Monowitz-Buna, is less known partly because it has been destroyed and there are not many leftovers, but also that Auschwitz serves as the icon for the Poles, and Auschwitz-Birkenau for the Jews, so there was no need for a third place of commemoration," Dr Alexander Korb, director of the Stanley Burton Centre for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at the University of Leicester, told IBTimes UK.

"During the Auschwitz trial in 1960, East German lawyers tried to draw the Monowitz camp from oblivion, because it seemed to be a suitable case to also get the West German industry, and capitalism in general, on trial," Korb added. "That attempt, however, largely failed, and only in the 1990s did the companies involved started to face stronger criticism and scrutiny."

Slave labour

Monowitz was created to provide labour for IG Farben's Buna Werke industrial complex, which produced synthetic rubber and liquid fuels. The SS leased out prisoners from the camp to work at the factories, charging Farben up to four Reichmarks per hour per prisoner, depending on their level of skill. Various other German industrial enterprises built factories around Monowitz, such as armaments manufacturer Krupp, headed by SS member Alfried Krupp.

Living in vastly overcrowded barracks like the Birkenau camp, prisoners incarcerated in Monowitz survived on extremely low food rations. "Buna-suppe" – a watery soup – was served as a minimal supplement to endure the intolerable working conditions.

Elie Wiesel, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning testimony Night, was a teenage inmate at Monowitz, along with his father from August 1944. "Bread, soup – these were my whole life. I was a body. Perhaps less than that even: a starved stomach," he recalled.

In reports sent from Monowitz to IG Farben's corporate headquarters in Frankfurt am Main, an engineer in charge of construction, Maximilian Faust, reported that violence and corporal punishment was necessary to keep production levels up.

While declaring his own opposition to "flogging and mistreating prisoners to death," Faust added that "achieving the appropriate productivity is out of the question without the stick."

Victims

To an enormous degree, the SS men from the Monowitz garrison were responsible for the conditions that prevailed in the camp. Slave labour, a lack of food, illness and executions reduced the life expectancy of workers at Buna Werke to just three or four months. For those working in the outlying mines, it was considerably less – just one month.

Although the SS and Farben employees destroyed prisoners' records shortly before the end of the war, death toll estimates of prisoners between January 1942 and January 1945 vary between 10,000 and 40,000. Historian Bernd C. Wagner suggested in 2000 that "in total, 30,000 prisoners died as a direct result of their work for the IG".

The American prosecutor at Nuremberg gave an indication of the death rate when he said the construction of the main factory chimney at Monowitz cost 300 lives alone.

Unlike Birkenau, which was largely repurposed to be an extermination camp as part of Nazi Germany's Final Solution in 1942, Monowitz was to exploit prisoners for slave labour. Those deemed no longer incapable of working were shot, killed by lethal injection or transferred to the gas chambers at Birkenau. "The main purpose at Buna was forced labour," Dr Korb said. "After all, it was the only concentration camp with the exclusive aim to exploit slave labour that was planned and financed by the private sector."

"The main purpose at Buna was forced labour," Dr Korb said. "After all, it was the only concentration camp with the exclusive aim to exploit slave labour that was planned and financed by the private sector."

"The clou is that extermination, as practised in Birkenau, and slave labour, as practised in Monowitz, were intertwined," he said. "The system of camps and subcamps was quite complex, but the bottom line is that prisoners who got sick, or too sick to get quickly recovered, would have been transferred from Buna to Auschwitz in order to be killed there, or to just die in the infirmary."

Death march

In mid-January 1945, as Soviet forces approached the Auschwitz concentration camp complex, the SS units began to evacuate prisoners from the camp. Nearly 60,000 prisoners were marched west from Auschwitz I, Auschwitz-Birkenau and Monowitz, moving north-west 30 miles to Gliwice, or due west for 35 miles to Wodzisław Śląski in western Upper Silesia.

In below freezing temperatures, prisoners, mostly wearing little more than thin uniforms and wooden clogs, were forced to make their way through several feet of snow. Anyone who lagged behind or collapsed was shot. At least 3,000 prisoners died on route to Gliwice alone, from execution, starvation or exposure. As many as 15,000 prisoners died during the evacuation marches.

Of the 650 Italian Jews in his transport to Monowitz in 1944, Italian chemist and writer Primo Levi, incarcerated in the camp for 11 months, was one of 20 who left alive.

"Even in this place one can survive, and therefore one must want to survive, to tell the story, to bear witness; and that to survive we must force ourselves to save at least the skeleton, the scaffolding the form of civilisation," Levi wrote in his 1947 memoir, If This Is A Man.

"We are slaves, deprived of every night, exposed to every insult, condemned to certain death, but we still possess one power, and we must defend it with all our strength for it is the last – the power to refuse our consent."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.