Brazil: Worst Drought in 80 Years Means São Paulo May Run Out of Water in Two Weeks

South America's biggest and wealthiest city may run out of water in two weeks if it doesn't rain soon. São Paulo, a Brazilian megacity of 20 million people, is suffering its worst drought in at least 80 years, with key reservoirs that supply the city dried up after an unusually dry year.

The severity of the situation in recent weeks has led government leaders to finally admit Brazil's financial powerhouse is on the brink of a catastrophe.

São Paulo residents should brace for a "collapse like we've never seen before" if the drought continues, warned Vicente Andreu, president of Brazil's Water Regulatory Agency.

Dilma Pena, chief executive officer of Sabesp, the state-owned water utility that serves the city, warned that São Paulo only has about two weeks of drinking water supplies left.

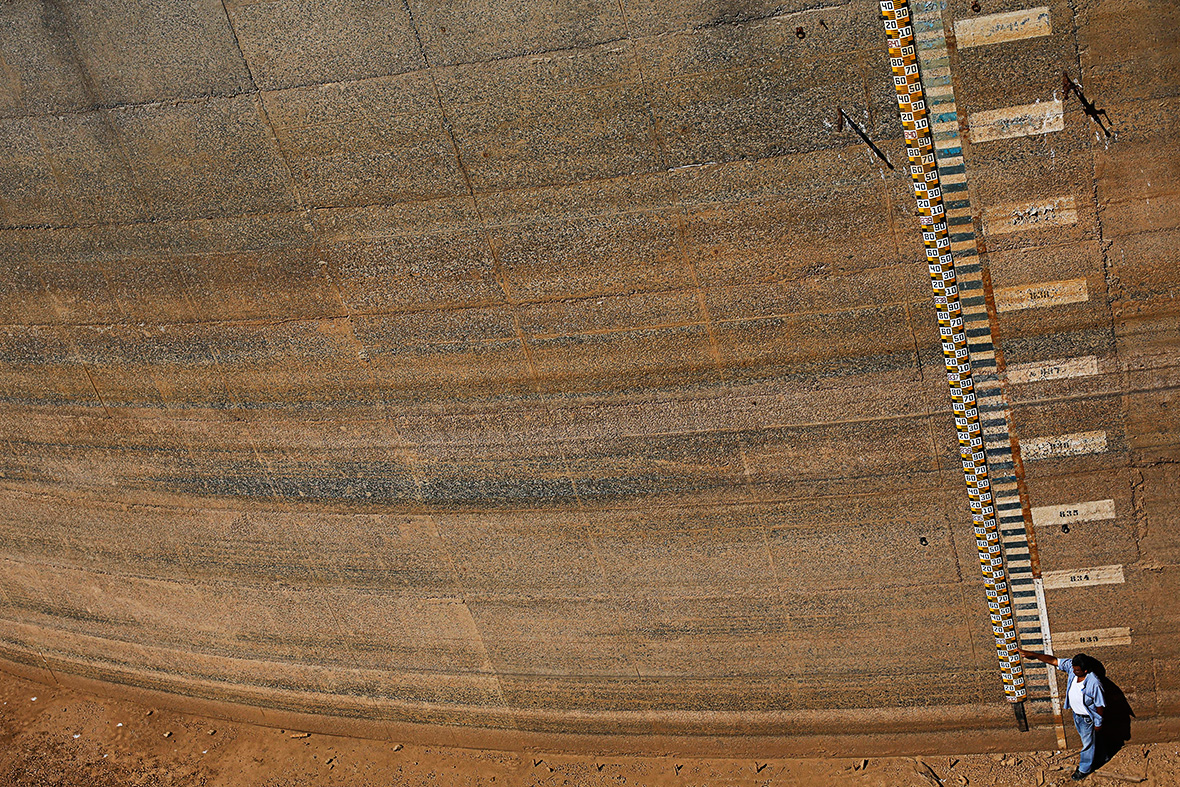

The Cantareira system, the main water reservoir feeding the region, dropped to just 3.4% of its capacity on 21 October, according to Sabesp.

The fall in the water level has exposed dozens of old cars dumped into the reservoir over the years, probably after being stolen.

Water pressure is reduced at night and people who cut back on use by 20% receive deductions in their monthly water bill. In some neighbourhoods, residents say water is cut for a few hours or days at a time.

The Estado de S.Paulo newspaper reported that the drought has affected close to 14 million people in 68 cities in the state. Almost 40 of these cities have started rationing water. Some of them receive water once every three days.

Sabesp, however, has assured customers that São Paulo won't run out of water, even though the main reservoir is nearly dry. A spokesman said Cantareira still has 40 billion litres of water thanks to emergency pumping below its flood gates. A second emergency pumping system will soon be ready and will provide an additional 106 billion litres of water to the Cantareira reservoir.

São Paulo State Governor Geraldo Alckmin said water from five other reservoirs in the city's metropolitan area is also being pumped into Cantareira.

One of the causes of the crisis may be more than 2,000km away, in the growing deforested areas in the Amazon region.

Antonio Nobre, a leading climate scientist at INPE, Brazil's National Space Research Institute, said: "Humidity that comes from the Amazon in the form of vapour clouds - what we call 'flying rivers' - has dropped dramatically, contributing to this devastating situation we are living today."

The changes, he said, are "all because of deforestation".

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.