British jobs for British workers: How a far-right meme went mainstream

Amber Rudd stirred outrage at Conservative conference by suggesting immigrants take jobs from British workers.

It's the meme in British politics that just won't die: foreigners taking British jobs. But where once it festered on the far-right, the virus slowly spread until it found its way into the mainstream.

Rooted in the fascism of the 1930s, it journeyed from the far-right to the hard-right, where it was diluted and rehabilitated, rising in popularity among the public amid mass immigration and economic insecurity. It has now been validated by mainstream politicians struggling to readjust to a new political reality, compounded by the vote for Brexit. Nationalism creeps.

Amber Rudd, the Conservative home secretary, suggested British companies could be forced to list how many of their staff are foreign as one of a number of proposals so immigrants "are filling gaps in the labour market, not taking jobs that British people could do".

Rudd continued that she wants "to look again at whether our immigration system provides the right incentives for businesses to invest in British workers". A severe backlash from business groups and her political opponents caused Rudd to soften her stance later, insisting the "name and shame" list, as one critic called it, was only being looked at and was not a concrete policy.

In economics there is the "lump of labour fallacy". This is a bogus theory that the labour market is a zero sum equation, where one worker displaces another. The reality is much more nuanced. Migrants bring skills, pay tax, spend money, spur economic growth — they help to create jobs and pay for public services.

Moreover, the evidence shows little if any significant impact on wages from immigration, other than a marginal negative effect on the lowest paid, which can be mitigated through the minimum wage and the welfare system. But the cheap foreigners taking British jobs idea lingers.

Oswald Mosley, leader of the British Union of Fascists, played on the lump of labour fallacy in the 1930s when he toured the country giving racist speeches. "No more admitting of foreigners into this country to take British jobs," Mosley told East Londoners in 1937, according to Globalising Hatred: The New Antisemitism, a book by the former Labour MP Denis MacShane.

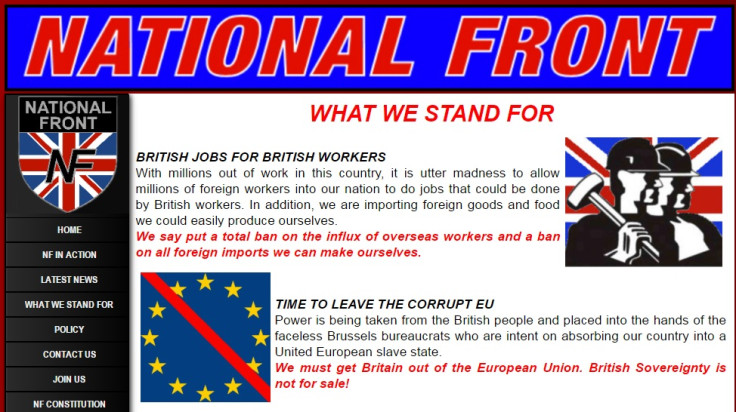

After the war, when Britain was trying to rebuild itself, the idea resurfaced amid waves of immigration from the Commonwealth, fuelled by the Conservative MP Enoch Powell's infamous "rivers of blood speech". In the 1970s, when it was at its peak, the fascist National Front preyed on the employment concerns of working class communities, pushing the rhetoric of British jobs for British workers.

It has remained a defining policy of the far-right. As the National Front faded, and the British National Party (BNP) rose, the same sentiments appeared again, coming to the fore in the late 1990s and 2000s amid mass immigration from the European Union (EU).

"We will ensure that our manufactured goods are, wherever possible, produced in British factories, employing British workers," said the BNP's 2001 manifesto. "When this is done, unemployment in this country will be brought to an end, and good, well-paid employment will flourish, at last getting our people back to work... We also call for preference in the job market to be given to native Britons."

But the BNP and National Front had long been toxic. There was now a fairly young right-wing party on the scene. Though not extremist, and of the economic right rather than left, the anti-EU United Kingdom Independence Party (Ukip) adopted a similar, albeit softer, line on foreign workers.

In its 2001 manifesto, Ukip argued for pulling out of the EU because of its policy of the free movement of people. Ukip said the focus should then shift to admitting skilled immigrants from Commonwealth countries instead.

"This does not mean, of course, that we advocate 'relying' on immigration to make up skill shortages," said the manifesto. "The Ukip is strongly committed to educating, training and promoting a skilled workforce of British people from all sections of British society, as is set out in our education policy."

But the "British jobs for British workers" phrase first entered the mainstream in a clumsy speech to unions by the then Labour prime minister Gordon Brown in 2007. He was taunted by David Cameron, then leader of the Conservative opposition, for lifting the words from the BNP and National Front. Others accused him of dog-whistle tactics.

Of course, underneath the words the sentiment was entirely different. Brown wanted to train up unskilled British people and the long-term unemployed to give them a better chance of competing in the labour market. It wasn't about shutting foreign workers out.

But his invocation and later defence of what he said helped normalise the use of language and ideas on the far-right in Westminster. Intentions are one thing. Interpretation — how that message is received by the public writ large — is another.

As trust in Westminster and the institutions of government dissipated amid spin, the Iraq War, MPs' expenses, the financial crisis, austerity, mass immigration and many other divisive issues, the fortunes of Ukip — led by the charismatic Nigel Farage and which portrayed itself as a fiercely anti-establishment, patriotic, and pro-British worker party — rose.

Ukip began to cause problems for the two main parties, Labour and the Conservatives, eating into both of their support bases. Both parties had to offer something to the old supporters abandoning them. But that also meant pandering to, and so legitimising, much of what Ukip was demanding — and we ended up with an EU referendum and tougher stances on immigration.

In 2013, Chris Bryant, Labour's then shadow immigration minister, touched on the British jobs for British workers theme in his pitch to voters, though underlying it was also a concern for the exploitation of foreign labour. Ed Miliband, the Labour party leader, had already said companies with more than a quarter of their staff foreign workers should have to tell Jobcentre Plus.

"Now, many employers say they prefer to take on foreign workers," Bryant said in a speech. "They have lots of 'get up and go', they say. They are reliable. They turn up and they work hard.

"But I've heard examples from across the country where employers appear to have made a deliberate decision not to provide training to local young people but to cut pay and conditions and to recruit from abroad instead, or to use tied accommodation and undercut the minimum wage."

Bryant added: "So yes, we need British employers to do their bit – working to train and support local young people, avoiding agencies that only recruit from abroad, and shunning dodgy practices with accommodation or to get round the minimum wage."

There were echoes of this in the 2015 election manifestos of the BNP and Ukip. The BNP's was blunt as ever: "British jobs for British workers: Local people must be given jobs before immigrants every time. There ARE enough jobs for our people – British people want to work!"

"British workers are suffering," said Ukip's. "Eurostat, the EU's own data service, revealed last year that EU migrants are more likely to be in work in Britain than Britons themselves. If we add to this the downward pressure on wages that has resulted from mass immigration, it is clear remaining in the EU is not favourable to British workers.

"By leaving the EU and restricting immigration through the use of an Australian-style points based system, we will give back some hope to British workers for a brighter future."

Amber Rudd's speech at the 2016 Conservative party conference shows how close the jingoistic "British jobs for British workers" concept now is to becoming government policy, smuggled in by a clamour to appease the growing populist nationalism encircling Westminster and tightening its grip by the year.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.