The Evil Within Reinventing the Horror Game: EGX 2014 Hands-on Preview

I can already see what will become of The Evil Within. Reviewers will call it cliched and boring; players will bemoan its clunky controls and camera. Mark my words – this is a game that won't get the credit it deserves.

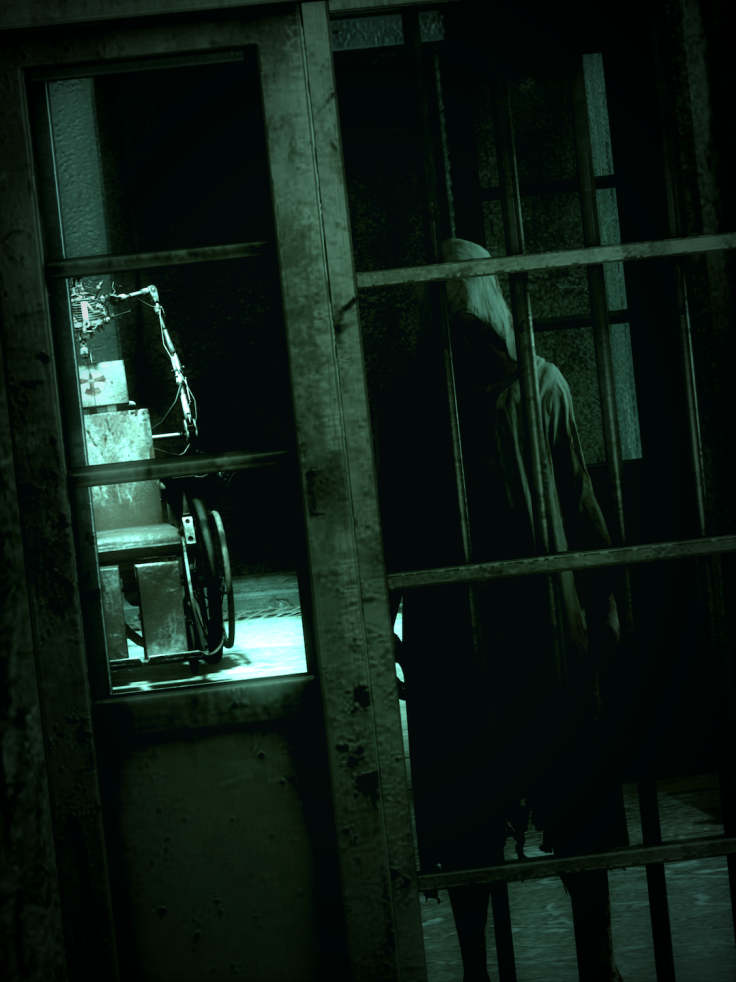

What Shinji Mikami, creator of the Resident Evil series, and his team at Tango Gameworks have made here is a horror game that plays on the conventions – or at least, modern expectations – of the genre. It's a third-person, over-the-shoulder style shooter, but you never have any bullets. You can use the right stick to rotate the camera, but it always hugs your character a little too tightly, meaning you can't get a decent look at your surroundings. You walk and manoeuvre slowly. There are puzzles, genuine puzzles, that require time and exploration to solve.

If you were alive in 1996, that may all sound familiar. The original Resident Evil was slow, complex and obscure. Mechanically, it was designed to put players on the backfoot, to diminish their sense of agency, their sense of purpose. The fixed camera angles meant players could only see what the director wanted them to see, which often excluded whatever creature was hiding around the corner. They could carry only a limited amount of items. Their characters were cumbersome and weak.

And that's how survival horror went until Mikami, unknowingly, shot himself in the foot by producing Resident Evil 4.

Resident Evil 4 was subsequently bastardised by lesser developers, spawning imitators like Dead Space, Gears of War, and Shadows of the Damned - the so-called "action horror" canon. After a few years, independent developers started producing quieter titles such as Slender and Amnesia. The central conceit here was that rather than carry weapons, the player would be unable to kill or harm the monster pursuing them, and would have to run and hide. It was a direct response to action-horror, which was a direct response to Resident Evil 4, which was a direct response to the sluggish, survival-horror that had thrived on the PS1.

Now it's come full-circle, and The Evil Within is a mix of all those games. But as I said, Mikami has shot himself in the foot. The players who still want action horror will decry this for bad functionality. The upstarts backing Outlast and Amnesia will bemoan a lack of scariness, and complain that you can't have combat and still be frightening. Mikami can't do right here for doing wrong. Horror games have become such a confab that everyone, everywhere, will find a reason to get pissed off at The Evil Within.

And that'll be a pity, because truly, this could be a revolutionary horror game. I said it earlier – it's playing, skilfully, with conventions and expectations.

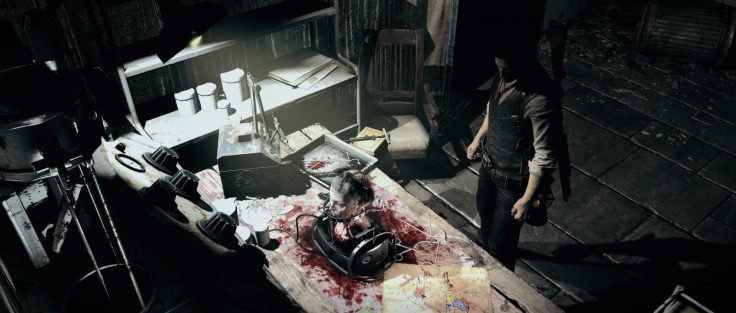

The exciting thing about The Evil Within is that it doesn't fit neatly into either modern horror category: it isn't an action-horror, nor is it a run-and-hide survival-horror game. There are elements here from all over. Mikami has taken inspiration from the entire last ten years of horror, plundering not just the loud AAA stuff, or the first-person PSN titles, but the homemade games found on browsers. There are mechanical nods to The Last of Us, but also creature and enemy behaviours lifted from things like Dreadout and One Late Night. There's the same sense of vulnerability that pervades Alien: Isolation, but also the splatterhouse fun of Dead Rising or Resistance.

The Evil Within isn't designed round a single conceit. Like the old Resident Evil games, it mixes puzzles, scares and combat. It also has stealth mechanics and, since this is 2014, pretensions of narrative. Reviewers might call it unfocused or over-ambitious. Personally, after several years of elevator pitch horror games, I'm delighted to play something with substance.

And Mikami remains a master of camera work. That aforementioned tendency for the lens to cling tightly to the player is the most distinct part of The Evil Within. It creates a terrific sense of claustrophobia, something other horror games rarely achieve. Enemies appear – you can hear them – but it takes a long time to wheel around and actually spot them. You have to move slowly – you have to take the time to stop and scout out the room. It's a deliberate move, rigging the camera to limit the player's viewpoint, but in today's climate of entitled, complaining fanboys, underwriting expectations of usability and interface is incredibly brave, and like The Blair Witch Project and its hand-held aesthetic, The Evil Within should be praised.

That use of camera in fact is this game in a nutshell. It isn't free-looping and easy to direct, but nor is it fixed to the wall and unmovable, like the Silent Hills and Resident Evils of old. It's a blend of both sensibilities. It's interactive and player-orientated, but also narrative and in service of the game's mood. It's emblematic not of horror as it is today, but of what it could be if The Evil Within succeeds - a mix of different styles and experiments, a cross between agency and vulnerability, meaningful action and actual scares.

The Evil Within

- Developer – Tango Gameworks

- Publisher – Bethesda

- Platforms – PS4, PS3, Xbox One, Xbox 360, Windows PC

- Release date – 14 October 2014

- Price – TBA

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.