HIV treatment: New inexpensive agents can block virus ability to replicate and develop resistance

New and affordable drugs that check the HIV virus from developing resistance are in progress, according to scientists who will present their findings at the 249th National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society (ACS) in Denver.

Instead of creating yet another cocktail of multiple drugs to tackle HIV virus, Dennis Liotta's team at Emory University designed compounds that hit multiple targets at once and also block the virus' ability to replicate.

The agents are inexpensive to prepare and should keep treatment affordable for millions in the developing world.

Most HIV drugs target viral proteins and hence have to be constantly altered when the viral proteins mutate and develop resistance to the drug.

In contrast, human proteins targeted in the new method do not mutate that often and the virus will find it tough to get around the new combination therapies, say the researchers.

The mechanism

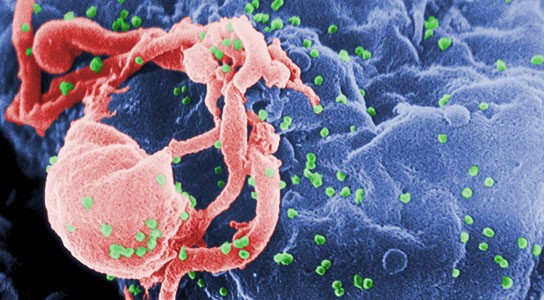

HIV fuses with human immune cells by interacting with key proteins and the viral proteins hijack the cellular machinery to make copies of themselves.

Pfizer has developed a compound that blocks HIV's interaction with one of those proteins, a co-receptor called CCR5.

But the virus can also use a second co-receptor, CXCR4, to enter cells.

While drugs targeting CXCR4 would be the way to tackle the virus, interfering with the protein, which regulates several of the body's inflammatory responses, could lead to serious side effects.

"With a chronic infection like HIV, it's very challenging to take a drug every day of your life if you have significant side effects," Liotta says. "This is a very high bar. No drug that functions as a CXCR4 antagonist for HIV has gotten over that bar."

The Emory team decided to search for compounds that bind both CCR5 and CXCR4 at the same time, while avoiding serious side effects.

Using a simple, inexpensive method to synthesise compounds that bind both co-receptors, they identified the most effective ones.

The group's partners at pharmaceutical company Bristol-Myers Squibb found that the compounds also blocked HIV reverse transcriptase, an enzyme that's key to the virus's ability to copy itself.

"The agents were active against CCR5, CXCR4 and HIV reverse transcriptase," Liotta says. "That was unprecedented. Also, they don't perturb any of the CXCR4 signaling pathways that lead to inflammation."

The lab is now working to further control the activity of these compounds, boost their potency and minimize their potential toxicity.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.