How Nepal's catastrophic earthquake swallowed the lives of impoverished women

Even before Rita Manandhar lost her home in the earthquake, she had already experienced tragedy. Her husband had died in Nepal's decade-long civil war between Maoist rebels and the state which ended in 2006, and she had been forced to surrender all her possessions to the Maoist insurgents. She was left to bring up two children alone. When the 7.8 magnitude earthquake struck the small, Himalayan nation last year, she lost any belongings she had managed to salvage.

"Whatever possessions I had were destroyed in the earthquake," Manandhar, 34, says. "I lacked economic support and was going through mental trauma."

More than 8,000 people were killed and thousands more left injured and homeless by the earthquake that devastated Nepal's Kathmandu Valley on 25 April 2015. It was the worst quake to strike the region in more than 80 years, costing the country nearly half of its GDP. Millions of Nepalis were affected, but women like Manandhar were hit particularly hard.

"Women in Nepal were the most affected after the earthquake, particularly mothers and babies, the elderly and disabled. Mothers and babies were more susceptible to injuries and death, and pregnant women faced delivering in the open with no skilled assistance," says Wendy Ngoma, programme manager at the NGO Womankind Worldwide.

Inequality based on gender and caste is widespread in Nepal. Women from the marginalised Dalit caste, considered "untouchables", live in poverty and are often subjected to violence. The decade of conflict in Nepal that left 30,000 dead reinforced gender discrimination, leaving many women trapped below the poverty line.

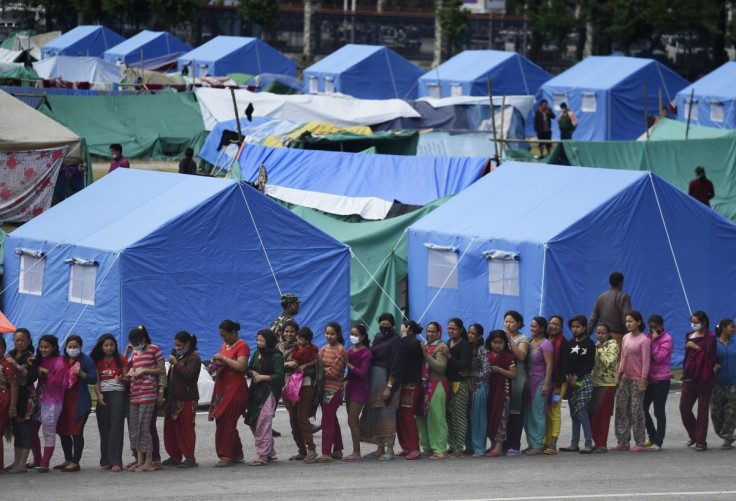

When the earthquake hit, many women were displaced from their communities and forced to live in temporary shelters, where they faced violence and exploitation. Disrupted health services, rampant disease and a lack of water and sanitation affected pregnant women, mothers and children.

Single women

Stigma surrounding single women − those widowed, unmarried or divorced − is rife because of the low social standing of women. If a woman loses her husband, she is considered a bad omen in society and shunned. Discrimination, violence and poverty is common and many live in substandard housing constructed from cheap materials that were the first to succumb to the earthquake.

Nucche Maya Maharjan, 50, was living in the Kathmandu village of Dharmasthali when the quake hit. In less than one minute, she had lost her husband, her home had collapsed and life as she knew it was over. A widow with no access to a proper shelter, she was forced to live in a damaged cowshed with another family member. "He was the backbone of our family," she says of her late husband a year later. "I can't believe he has gone."

"Single women were particularly vulnerable because of women's economic and social dependence on men," says Ngoma. "Nepal is a society where family structures are led by men and where women tend to be married early, discouraged from finishing their education and experience violence on a regular basis."

Although countries rushed emergency aid into Nepal after the earthquake, single women found it difficult to access relief supplies without a male head of the household.

"Women gaining access to relief, services and goods immediately after the earthquake were often dependent on having a male relative to support them," Ngoma adds.

Exploitation

One of the poorest countries in the world, Nepal is a focal point for organised smuggling networks, many of which operate across the border with India. Between 10,000 and 15,000 women and children are trafficked from Nepal every year, according to the UN, and campaigners have raised concerns of a rise in trafficking in the aftermath of the earthquake.

Many Nepali women are still living in cramped and unsanitary communal shelters and displacement camps one year later, where they face a heightened risk of abuse and exploitation. Girls from single-mother-headed households are particularly vulnerable to trafficking.

In July 2015, Indian police said they uncovered a human-trafficking network that lured hundreds of young women from earthquake-hit areas of Nepal to the Gulf with the promise of lucrative jobs, where they were instead sold for sex work and manual labour.

"Single and widowed women became the immediate prey after the tragic event, they became victim to mental and physical harassment, sexual abuse, health degradation and human trafficking," says Lily Thapa, head of the Nepalese NGO Women for Human Rights (WHR).

"Sexual exploitation and gender-based violence inside the temporary shelters also increased due to the common and open toilets, open sleeping grounds and lack of electricity," Thapa says. "There were also serious concerns about the vulnerability of women to sexual and gender-based violence, particularly for those women who don't have male family members."

Hope

Although the road to recovery will be long for Nepal, Womankind and Women for Human Rights (WHR) have provided a lifeline for many women impacted by the earthquake, including Manandhar. She has been able to earn a small living through weaving and her children have been able to continue their education.

Many impoverished women still face low rates of land and home ownership and don't have access to the funds to construct homes destroyed by the quake, but Maharjan has been able to rebuild her house in Dharmasthali with help from the charities. "I never thought I could rebuild my house; it wouldn't be possible without the support of Women for Human Rights."

In the weeks and months following the disaster, dignity kits, including sanitary pads, underwear and mosquito nets, were distributed. Counselling was provided and women were helped obtain legal documents lost in the earthquake, as well as food, medical assistance and safe living spaces.

"I cannot believe it's already been a year since the earthquake," Thapa says. "We had to see and hear the horrifying stories from so many women, but thankfully we were in a strong position to be able to offer support and help women rebuild their lives. The lives which were lost cannot be brought back but we have been able to spark hope in the hearts of women and help them overcome their fear."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.