Huge, rare diamonds are born in pools of liquid metal deep below the Earth's surface

"Superdeep" diamonds form as far as 750km down into the Earth – that's more than the length of Florida.

The world's largest, purest diamonds form in pools of molten metal in the Earth, much deeper than the majority of more common diamonds, scientists say.

The largest and rarest diamonds are made in a different way to more ordinary, smaller diamonds, according to a paper in the journal Science.

"People have recognised for a long time – as long as we've been mining diamonds – that some of them, especially the larger ones, look a little bit different. They have slightly different physical characteristics, and you can pick them out by eye," study author Evan Smith of the Gemological Institute of America told IBTimes UK.

But what sets apart the 3,106-carat, 620g (1.4lb) Cullinan diamond from the more modest rocks you might see in a high-street engagement ring?

It's been a hard question to answer scientifically. Surprisingly, great big valuable diamonds are quite hard to get hold of for scientific experiments. But scientists have now managed to find some answers by studying the offcuts from the largest diamonds.

The most sought-after diamonds are hefty, pure and have few traces of impurities in them. This means that they are essentially a blank slate – they give very few clues as to how they formed becuase they are just carbon, about as pure as it comes.

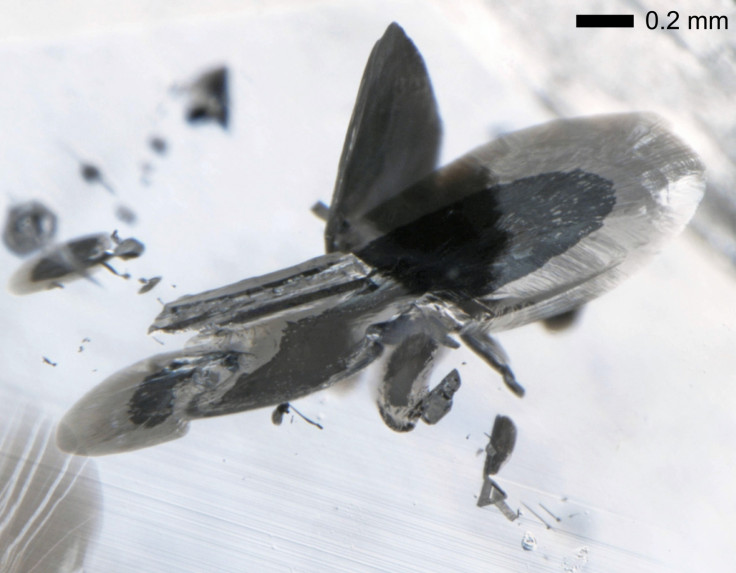

But they don't start off that way. When they come to be cut there may be some parts that have to be cut off to give a large, pure diamond. These offcuts can contain clues as to how the diamonds formed.

It's these offcuts that scientists have been studying to find out these large diamonds – known as CLIPPIR diamonds – form. The offcuts were found to have traces of minerals such as majoritic garnet, which only forms under very great pressures, says Smith.

"This is the first time that people have tried really hard to get offcuts from diamonds like this and have succeeded, and found inclusions – bits of non-diamond material trapped inside the diamonds."

These traces of minerals helped to put an estimate of the depths at which the diamonds form: anywhere as far as 750km below the surface of the Earth. That's more than the length of the state of Florida, and more than three times as deep as some of the less spectacular specimens.

The offcuts also held traces of metals such as iron. This tells us something about the composition of the Earth's deeper mantle, which has been something of a scientific mystery. "There are parts of the deeper Earth that must contain this metallic phase," Smith says.

These metals could also hold the key to the large diamonds' purity. Pockets of molten metal could help the diamonds to grow to such great sizes.

"Perhaps the diamonds are growing from a liquid metallic medium," says Smith. "It could be just a small pocket of liquid metal where the diamond is growing."

This is important because metallic iron is very good at dissolving carbon, Smith says. This could allow carbon to "float around" in the iron and give the diamond a chance to increase in size.

"So if you want to grow a big diamond then this is a good place to do it."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.