Museo Atlántico: Europe's first underwater art museum opens to the public

As it is 14 metres under the surface of the water, the museum is accessible only to scuba divers and snorkelers.

Europe's first underwater art museum has opened to the public. Museo Atlántico, the brainchild of British eco-sculptor Jason deCaires Taylor, is located off the coast of Lanzarote. As it is 14 metres under the surface of the water, the museum is accessible only to scuba divers and snorkelers. This monumental project has taken two years to complete and aims to create a strong visual dialogue between art and nature.

Taylor told IBTimesUK he cast many of the human sculptures from real people. They are grouped in several installations that draw attention to issues such as climate change, conservation and migration. The largest installation – entitled Crossing the Rubicon – comprises a group of 40 people walking towards a gateway in a 30-metre long barrier. The figures aren't paying attention to where they are going − some have their eyes closed, some are taking selfies, others are engrossed in their phones. Taylor says this work is about climate change and how mankind seems to be heading blindly towards a point of no return.

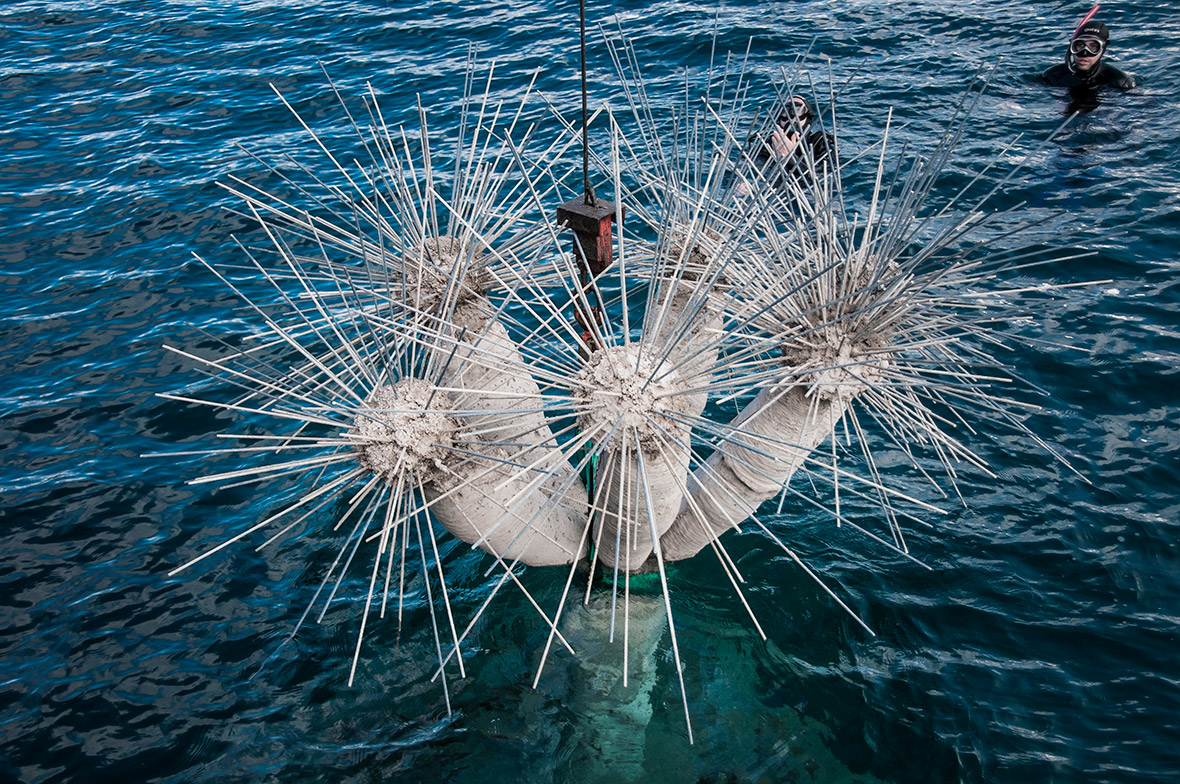

The artist has created an underwater botanical garden, filled with the island's natural flora – as well as human-cactus hybrids that suggest humanity and nature working together in perfect harmony. Over time, the garden will bloom in another way, as the local marine life colonises it. A piece called the Portal depicts a hybrid animal/human sculpture looking into a large square mirror, which reflects the moving surface of the ocean. Forming part of the underwater botanical garden the concept is intended to portray water within water, an interface or looking glass into another world – the blue world. The mirror is elevated on a series of cactus forms that contain a series of small compartments and "living stations" designed to attract octopodes, sea urchins and juvenile fish.

An installation called Deregulated consists of a children's playground enjoyed by suited businessmen. A swing, a see-saw and more all demonstrate the arrogance of the corporate world towards the natural world. The see-saw references a petroleum extraction pump, a comment on the control of these fossil fuels and their unregulated use. The dolphin ride is indicative of the burden we are placing on marine species and its ultimate collapse if left unchecked.

Another piece, The Raft Of Lampedusa, depicts African men and women in a sunken dinghy on the seabed. The title of the piece is a reference to The Raft Of Medusa, a Théodore Géricault painting of people clinging to a makeshift raft after a French frigate ran aground off the coast of Mauritania in 1816. There were not enough lifeboats for everybody on board, so the captain and other dignitaries sailed off in them, leaving 147 people to board an unstable raft. Conditions on the raft were horrific. Many people were washed out to sea, others were killed in bloody fights and some survivors engaged in cannibalism. When the raft was finally rescued after 13 days at sea, only 15 men were still alive. The case became an international scandal, with the deaths being blamed on an incompetent captain who had abandoned his responsibility. Taylor says his Raft Of Lampedusa points to European governments' unwillingness to accept responsibility for the migrant and refugee crisis. The Canary Islands are the first port of call for thousands of people from west Africa trying to reach Europe. Some of the figures in Taylor's underwater dinghy were cast from people who had made this perilous journey.

An installation called The Immortals was moulded from a local fisherman from La Graciosa island, on the north coast of Lanzarote, and represents a traditional funeral pyre.

The final exhibit in Museo Atlantico is the Human Gyre, with over 200 life-size figurative works creating a vast circular formation or 'gyre'. Consisting of various models of all ages and from all walks of life, the positioning of the figures constructs a complex reef formation for marine species to inhabit and is a poignant statement for visitors to take with them at the end of the tour. The artist says he hopes a visit to Museo Atlantico may lead to a closer understanding of our relationship with the natural marine environment and appreciate the need to value and protect this fragile ecosystem in order to save ourselves.

These sculptures are not just for humans – they serve as an artificial reef, encouraging greater biodiversity. They are already being frequented by angel sharks, shoals of barracuda and sardines, octopodes, marine sponges and the occasional butterfly stingray. This is not Taylor's first underwater sculpture park. He has created similar undersea museums in the Bahamas and Mexico. His plain grey cement figures are slowly being transformed as they are colonised by colourful coral, anemones and other forms of sea life.

The museum takes up 50m<sup>2 of lifeless sandy seabed, built with neutral pH materials that respect the environment, and all the pieces have been designed to adapt to the endemic marine life. The project has been promoted by the Art, Culture and Tourism Centres of the Cabildo of Lanzarote, whose network it is now part of. It has also been co-financed by the Government of the Canary Islands.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.