Northern Ireland: Victims fear 'amnesty by the back door' as crisis deepens

Janet Donnelly was eight years old when her father, Joseph Murphy, was shot when the British Army killed 11 civilians and wounded others in the tiny community of Ballymurphy in West Belfast, over a period of 36 hours.

Murphy, conscious of the disorder on the streets, had gone out to look for his sons when soldiers from the Parachute Regiment opened fire on the crowds. He ran into a field to take cover and was shot in the leg. He only lived for another 13 days.

Years after what became known as the Ballymurphy massacre, Donnelly, now a grown woman married with her own children, decided to ask her mother how her father had died. How could a gunshot wound to the leg prove fatal?

She explained that it was what happened after the shooting that cost her husband his life. That day, 9 August, 1971, the dead and wounded were rounded up, piled into the back of an army vehicle and taken to the local barracks, known locally as the Henry Taggart.

There, he told his wife, the soldiers had beaten them. By the time he arrived at the Royal Victoria Hospital, a couple of miles away, the doctors couldn't operate; his injuries were too severe. Gangrene set into his leg and following an amputation, he died of septicemia.

Murphy's death was one of more than 3,000 in Northern Ireland over a 30-year period of civil war, known as The Troubles, which pitted Catholics and Protestants against each other, local terror groups and the British government. The legacy of lives lost continues to hang over the country, with victims across the religious divide demanding justice for their loved ones.

It was her own quest for justice that led Donnelly to an event hosted by Northern Ireland's Department of Justice (DOJ) at Stormont. Her friend, retired human rights lawyer Padraigin Drinan, had said that the meeting was about dealing with the past.

As it turned out the event, on 6 August – nearly 44 years since the day her father was shot – was to consult with various groups about a new body which would offer limited immunity to perpetrators, among other arrangements.

On 23 December the year before, Northern Ireland's political parties – in the wake of talks over a dispute about flags and emblems, following the decision to fly the Union Jack on Belfast's City Hall only on designated days – struck a deal known as the Stormont House Agreement.

Flags had been the hot-button issue for the previous 18 months so few took the time to read what the agreement said about dealing with unsolved cold cases or those, like that of Donnelly's father, where the perpetrators were broadly known but no prosecution was forthcoming.

Eight months later, with another round of talks ongoing between the parties – this time to prevent the government from falling – victims discovered what was planned for them. What followed has been a diplomatic crisis and even if the parties come to yet another agreement, the question is whether they'll be able to take the electorate with them.

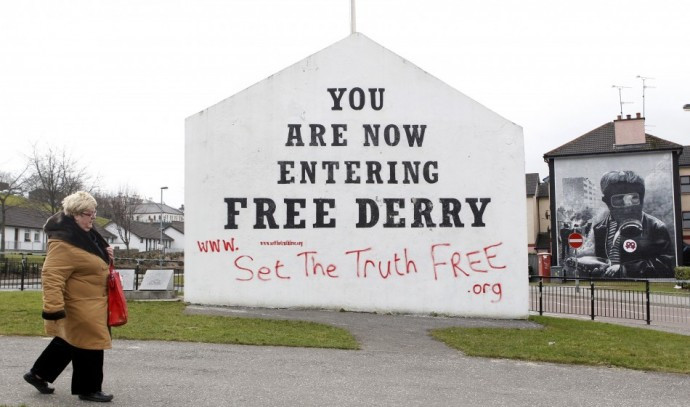

The first Kate Nash knew of Stormont's proposals on historical crimes was when she saw an update on Facebook from a local victims' group. At a recent meeting with the Department of Justice in Derry – a city two hours away from Belfast – DOJ representatives had announced that the police investigation into Bloody Sunday could be transferred to the new Historical Investigations Unit (HIU), a new body which would tackle historical crime.

As per the Stormont House Agreement, it was to replace the Historical Enquiries Team (HET), a similar body tasked with reviewing cold cases to see if any leads had been missed in the original murder investigation.

There were a number of mass killings during the Troubles. Mention it and depending on which side of the peace line – the barricades that continue to keep the two communities apart – people will usually know what you're referring to.

La Mon: 17 February 1978, 12 killed and countless others injured in a fireball created by an IRA bomb, left by a window of the La Mon Country House Hotel. McGurk's: 4 December 1971, a bomb left by Protestant terror group the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) outside McGurk's Bar in North Belfast kills 15, including two children.

But Bloody Sunday is the one everyone knows, regardless of religion, immortalised as it is by the U2 song, Sunday Bloody Sunday. Some 26 unarmed civilians shot by members of the Parachute regiment – the same regiment that was in Ballymurphy a few months before. 14 people died of their injuries.

Nash's brother, William, was just 19 when he was killed that day. Ever since, Nash and her sisters have been fighting for the soldiers involved to be tried for murder.

News of the police investigation being transferred to the HIU came as a surprise to her. She began to make enquiries, eventually meeting with Padraigin Drinan. Together, along with a loose group of other victims, the pair have created a publicity crisis over the Stormont House Agreement's proposals – which they believe are aimed at allowing perpetrators to walk away from their crimes.

Under the agreement, a new body called the Independent Commission for Information Retrieval (ICIR), will allow those with knowledge of a Troubles-related murder – namely, those who carried out the killing – to confess their crime in exchange for "limited immunity".

Their identities will not be shared with their victims' families and the information they've given cannot be used in a prosecution against them (although, if the HIU finds evidence elsewhere which proves they were behind the crime, they could still end up in court). While the DOJ and politicians are keen to stress that it isn't an amnesty, victims aren't convinced. "It's amnesty by the back door," said Drinan.

What's made it worse is that the DOJ appears to have tried to quietly sneak the legislation through without drawing public scrutiny. Invitations to workshops where it was to consult with invited groups on the proposals – the one Donnelly and Drinan attended – went out less than two weeks before the first event.

In an email, the department acknowledged that it had neither advertised the events on its website or in the local press, arguing that it had invited many groups and that it was not a public consultation.

They subsequently agreed to meet with victims in Derry on 26 August but cancelled the meeting at 6.20pm the evening before, saying that it had now become a public event, after being reported in the Belfast Telegraph, and arguing that it would not be appropriate for them to attend because, again, they weren't engaged in a public consultation.

In private telephone conversations with the head of the department's legacy unit, Brian Grzymek, victims said he acknowledged that the legislation underpinning the ICIR and other proposals emerging from the Stormont House Agreement was being "rushed through". Danny Bradley, whose brother Seamus – an IRA volunteer – was killed in 1972, said Grzymek told him that they were aiming to have the legislation passed by October 2016.

A source close to the situation claimed that, in a private meeting with the Department of Justice, the Northern Ireland Office – realising that the arrangements could prove unpopular with the local electorate – had agreed that the legislation would be passed through Westminster to avoid scrutiny from the likes of local politician Jim Allister of the Traditional Unionist Voice (TUV) party.

Allister, a Unionist politician, is known for not going quietly along with the other parties and is viewed as a thorn in the side of the Establishment, like a right-wing, Conservative version of Jeremy Corbyn.

When reached by telephone, Allister said, "It's never been adequately explained why the legislation was moved to Westminster. I think the reason for this was twofold; one was to avoid scrutiny by local MLAs and the second was so that local parties like the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) could say this was Westminster legislation and had nothing to do with them."

Allister could be right. Yet it seems plans for limited immunity have been in the pipeline for some time. Confidential documents seen by IBTimes UK, the Alliance Party - of which the DOJ's current minister, David Ford, is leader – show that as far back as 2013, the concept was being considered.

Alliance would strongly reject attempts to rewrite history. As such any notion of an amnesty would be inappropriate. Furthermore, it would run counter to the terms of the European Convention on Human Rights.

"However, it is worth considering offering a much more limited, and less loaded immunity from prosecution related to the specific information that certain persons may wish to provide to any legacy commission."

With talks at Stormont ongoing – the current crisis triggered by the murder of republican ex-prisoner Kevin McGuigan, allegedly by the IRA, raising questions about whether the organisation is still active – the storm over the ICIR and whether or not it represents an amnesty, as well as questions over how effective the HIU will be, has added a further complication to negotiations.

Parties have been contacting victims privately to lobby them to back the proposals. Nash said that some journalists had contacted her to say that they'd been put under pressure by politicians and government bodies because they'd covered the story. With local elections looming early next year, it seems that, whatever they say to the contrary, most of the parties are keen to keep the Stormont House Agreement – and the government – in place.

In response to this story, the Northern Ireland Office issued a statement: "The five main parties agreed that a single bill in Westminster was the best way to deliver what everyone signed up to in the Stormont House Agreement.

"The legislation will include a mixture of devolved, reserved and excepted matters. The assembly will be able to consider and vote on a legislative consent motion for Westminster to legislate in a devolved area in due course."

The Alliance Party and the Department of Justice did not respond to requests for comment.

Lyra McKee is a freelance journalist based in Belfast. Follow her on Twitter: @LyraMcKee

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.