Police brutality videos provide vital evidence – but it's a tragedy that we need to keep filming

They provide evidence of a society terrified of those who are supposed to protect them.

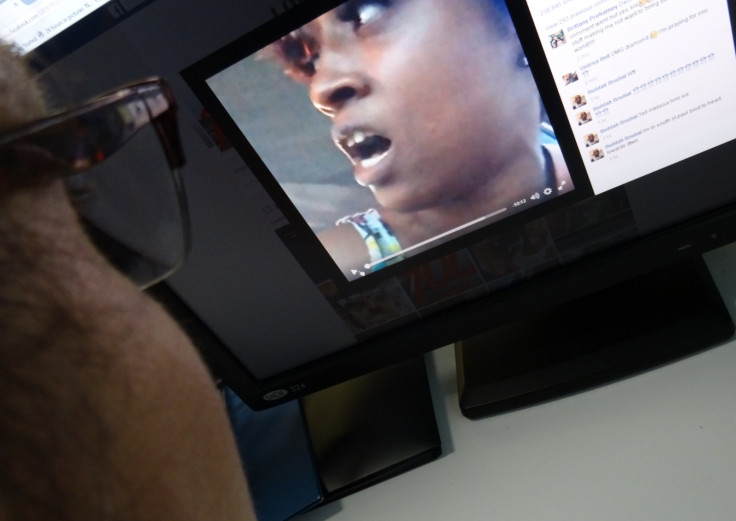

For the past few years, black life and death have remained eerily juxtaposed on our social media timelines.

It is widely accepted that 'Black Twitter' provides the wind beneath the fledgling little blue birds wings. From 'fleek' to 'dabbing' to some of online's most famous comedians, it continually gives life to a platform many consider to be dying. But as often as a new hashtag appears which was invented by the community, so do images of broken black bodies and the hashtagged names of their owners.

On Wednesday, another video of a black man shot by the police found its way online. But due to the regularity with which black men die at the hands of police in America, the story of Charles Kinsey's shooting is primarily noteworthy because he's alive to tell it. Widespread footage shows the behavioural therapist from Miami on his back with his hands in the air, calmly and clearly explaining to the police that he was a mental-health worker caring for the autistic patient who sat next to him, and that he was only carrying a toy truck. He is then, off-camera, shot in the leg.

As far as these stories usually go, Kinsey is one of the lucky ones. While the definition of 'good luck' would not usually consist of returning from a day's work with a gunshot wound and in a pair of handcuffs, Kinsey is a black man in America. The outcome for others that have occupied the same profile – unarmed and black – has often been fatal.

The footage joins an ever expanding list of instances of police brutality that have been 'fortunately' videoed. But the documentation of these shootings is less about serendipity and more about necessity. It is no coincidence that the recent deaths of Philando Castille and Alton Sterling were recorded. Nor those of Freddie Gray, Walter L. Scott, Mike Brown and Eric Garner.

African Americans are in an almost Orwellian reality where by reflex witnesses reach for their phones - but not to dial 911

Harrowing, graphic images from history often serve as a reminder of a past we hope not to return to. But the videos of black bodies strewn across social media are more of real-time SOS than a reminder. A cry for communal help when the police are the ones pointing the gun. And as the footage and bodies continue to pile up, and conviction rates show no real signs of doing the same, African Americans are in an almost Orwellian reality where by reflex witnesses reach for their phones – but not to dial 911.

When Philando Castile was shot by a police officer a few weeks ago, the bloody aftermath was streamed by his girlfriend, live. During the broadcast of his final moments, many wondered how Reynolds remained so stoic in dystopia. How, with her boyfriend's body bleeding life beside her and a toddler in the back seat, she held her voice and phone steady. How she managed to shape her mouth to call her boyfriends killer 'sir' and not once disobey as he frantically spat orders at her. By her own account, it is because she simply had to.

"I wanted everyone in the world to know how much [the police] tamper with evidence and how much they manipulate our minds," she told a crowd hours after her boyfriend's death.

"I wanted it to go viral so that people could determine themselves as to what was right and what was wrong."

The Baton Rouge police department say police "body cameras came dislodged," when tackling Alton Sterling to the ground before they killed him. Had it not been for Abdullah Muflahi – the owner of the convenience store Sterling was shot outside of – the story may well have ended there.

They provide evidence of a society terrified of those who are supposed to protect them and a society aware that black blood does not always hold up against white words.

"As soon as I finished the video, I put my phone in my pocket. I knew they would take it from me, if they knew I had it. They took my security camera videos. They told me they had a warrant, but didn't show me one. So I kept this video for myself. Otherwise, what proof do I have?"

These videos provide more than evidence on what occurred during each incident. They provide evidence of a society terrified of those who are supposed to protect them and a society aware that black blood does not always hold up against white words.

"Sir, why did you shoot me?" Kinsey asked the officer. He responded he didn't know. North Miami police later said the officer opened fire after attempting to negotiate, and they were aiming for the autistic man.

But the black community knows full well why so many black people are needlessly killed by the police. And though systematic racism and structural inequality can't be caught on camera, society is ensuring their outcomes continually are. The sharing on social media of these images and videos makes my blood run cold and it's scary how numb we've become to such visual horror. A world where the evidence does not exist however, is even more terrifying.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.