Prevent Strategy: Senior doctor calls for boycott of government's 'unethical' counter-terrorism programme

One the country's leading medical bodies is to investigate whether the government's counter-terrorism programme violates doctor-patient trust, after a senior member branded it "unethical". IBTimes UK has learnt the Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCP) will create a working group to see how the controversial Prevent strategy has impacted psychiatry since it was extended to the NHS last year.

Prevent is intended to combat extremism of all kinds, whether it is violent or otherwise. Legislation passed by the government last year meant all public bodies, including schools and hospitals, were now required to look out for and report signs of radicalisation.

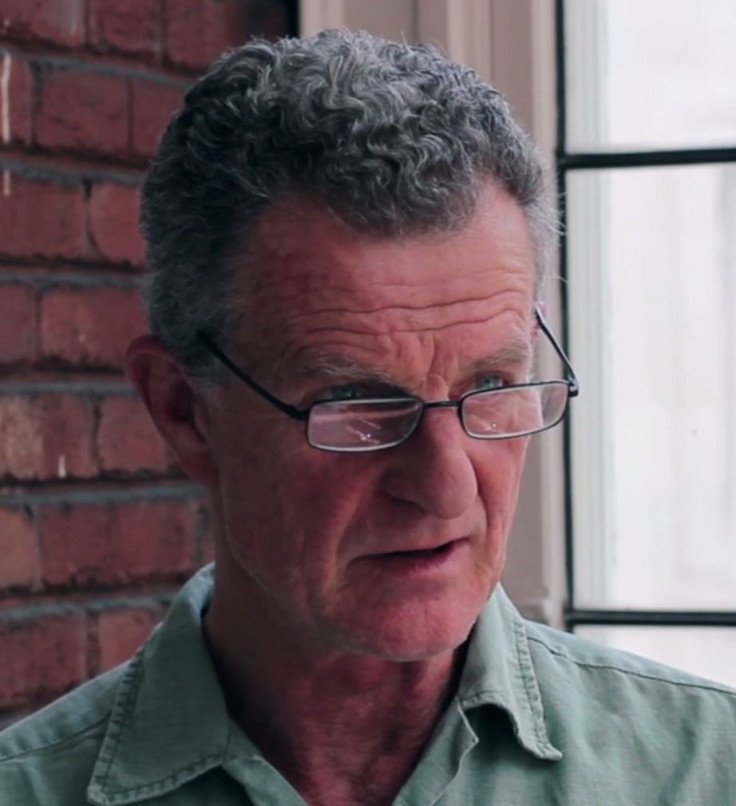

But a senior member of the RCP told IBTimes UK the measures represented a "corrosion of the ethics of the doctor-patient relationship". Dr Derek Summerfield, a consultant at South London and Maudsley NHS Trust and honorary senior lecturer at the Institute of Psychiatry, said Prevent was leading to "a duplicitous deviation from the medical assessment, advice and treatment that has brought the patient to us".

He pointed to a colleague's case in which a Muslim patient, with symptoms of mild depression, had been referred for a psychiatric assessment by his GP because he said he "got angry watching events in Syria on television".

Dr Summerfield said: "A GP would never have referred someone with mild depression for a psychiatric assessment. It was only because he mentioned Syria.

"The government is trying to pitch Prevent as an extension of ordinary safeguarding practices but in reality it's a perversion of ethical medical practice. It encourages us to essentially spy on our patients.

"Psychiatrists have access to the deepest and most intimate thoughts of patients and Prevent, which appears to equate to 'thought crime' and spying on Muslims, could see patients becoming afraid of what they tell us.

"As it takes on a life of its own, doctors may also no longer focus their attention on treating their patients but instead start thinking about whether they should be referred to Prevent. It could start guiding the questions they ask and how they approach their patients."

In an article published this month by the British Journal of Psychiatry, Dr Summerfield said a growing number of his colleagues had expressed "unease" over mandatory Prevent workshops currently being given to tens of thousands of NHS staff. He complained medical professional bodies like the General Medical Council (GMC) had so far ignored the ethical implications, and suggested other doctors would join his calls for a boycott.

The RCP today confirmed to IBTimes UK it had now created a working group to look at the implications of the programme for its members. It said the body is currently finalising its remit, adding: "This will be determined by the group when they have considered the draft Terms of Reference but [it will] include Prevent."

'Spying' on Muslims

Prevent has been a government priority since its creation more than a decade ago. It forms part of the post-9/11 counter-terrorism strategy "Contest", which seeks to combat against people becoming radicalised or exposed to extremist material.

Last year, the passing of the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act placed a new legal duty on all public sector workers, including doctors and teachers, to "prevent people from being drawn into terrorism". The government insists the stategy is about "safeguarding" and has successfully stopped the spread of extremism.

But Prevent has been attacked by numerous community leaders, academics and faith leaders who say it has equated to "spying" on Muslim communities. Critics also accuse it of now encouraging workers in the public sector, like teachers, to be suspicious of Muslims.

The impact on the education sector has seen a rising number of children in England and Wales referred by teachers to the government's deradicalisation programme.

One case last year saw a 14-year-old boy questioned about the Islamic State (Isis) after a classroom discussion about environmental activism saw him mention the word "ecoterrorist". Concerns were raised by teachers at Central Foundation School in North London and he was taken to a room days later to be questioned by officials.

Another case in December saw a teacher reporting a 10-year-old Muslim boy after he misspelled the word "terraced" when he wrote he lived in a "terrorist house". It led to Lancashire police officers arriving at the child's home the next day, with his parents telling the BBC their son is now "scared of writing, using his imagination".

Dr Summerfield said the implication of Prevent for psychiatrists was potentially more ethically problematic than other professions. He said: "We've seen a rising number of children being referred under Prevent. I am very worried this will happen with patients.

"Psychiatrists are trusted with their patients' most intimate inner thoughts, and for the state to ask us to spy on them would break that trust."

Doctors are already compelled under the Terrorism Act 2000 to contact the police should they believe a patient be involved in terrorism. They also have duties under existing safeguarding legislation.

In a letter to Parliament's health select committee last year, the chief executive of the GMC, Niall Dickson, said Prevent "does not alter the circumstances in which doctors are obliged to report concerns about patients". He also said doctors and nurses should continue to abide by existing laws on patient confidentiality.

But a 2015 Prevent training document published by NHS England said healthcare was seen as "one of the best best placed sectors to identify individuals who may be groomed in to terrorist activity", citing its 1.3m workforce and 315,000 daily contact with patients in England. It insisted it was encouraging a "proportionate" adoption of the strategy.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.