Stealth taxes hit the poor hardest and treat the public like they're stupid

Many voters are willing to pay more tax for better public services but politicians aren't upfront with us.

Politicians are very often defined by their opponents rather than by anything they have actually done.

This is a truism, but it is a truism that bears repeating. If the public gets it into their heads that you are, say, soft on terrorism (Jeremy Corbyn), out of touch (David Cameron), or some kind of war criminal (Tony Blair), it is usually because your opponents have hammered away at that point unremittingly over several years.

Politics ultimately boils down to who can most effectively define themselves enough to prevent their opponents doing it for them.

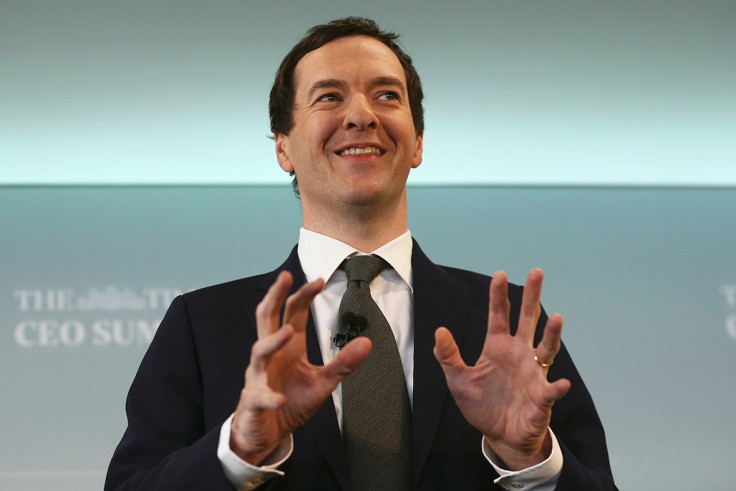

But chucking handfuls of mud at the opposition can sometimes obscure things for those throwing it. Take the former chancellor, George Osborne. To his opponents, Osborne is a low-tax Conservative. He is also socially liberal and believes that the state – and invariably the tax burden – grew too large under successive Labour governments.

And this is, for the most part, an accurate summation of Osborne's political raison d'être. It is how he would probably define himself privately, perhaps publicly, and, more importantly, it is how his political opponents did define him while he was in office, albeit in language a good deal less varnished: Osborne's austerity programme was a form of "ideological class war", according to the former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis.

But is the categorisation of the former chancellor accurate? To a degree yes: Osborne, before he was dethroned by Theresa May, set in motion what will, by 2020, be the longest "fiscal consolidation" – cuts, in other words – since records began. Some of the detail in this respect is eye-watering: for every £1 received by councils in 2010/11 they received just 73.6p by 2013/14. Local authority spending per person was cut by 23% in real terms between 2010 and 2015, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, with poorer areas bearing the greatest burden.

When those protesting against the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition mocked David Cameron's trite mantra that we were "all in it together", they had a point: the coalition rolled back the state with the most relish in those parts of the country where a bigger state was probably most needed.

But Osborne's opponents got the other half of the equation wrong. By the time the former chancellor left office last year, he hadn't turned Britain into a low tax economy at all. In fact, quite the opposite had happened: due to a large increase in stealth taxes on Osborne's watch the tax burden is on course to hit 37% of GDP by next year – its highest level in 30 years.

Counterintuitive facts of this sort typically get picked up by right-wing think tanks and City AM op-ed writers as unassailable proof of a lack of ideological vigour on the part of the former chancellor. Like the communists of the previous century (albeit without the pyramid of corpses) the unwillingness of the flesh and blood world to adhere to the course set out by theory is evidence not of the falsity of the theory, but of the unsatisfactory rigour with which the theory has been applied.

But for those of us who try to dwell in the world as it is – rather than the world as it appears in a textbook – the apparent paradox at the heart of George Osborne's time in Number 11 is rather obvious: he quickly found out that some of the things that cost money are quite important. Implementing a programme of swingeing cuts (while raising the inheritance tax threshold on family homes to £1m/$1.2m) also brings with it knock-on costs. One of the reasons the NHS is now under strain is due to a reduction in the money allocated to social care. The huge and lamentable rise in homelessness carries a similarly large tab.

Add to that the money lost through things like the trumpeted tax-free allowance and the rise in self-employment (much of it bogus) and you soon find yourself scrabbling around for new sources of income. Osborne plugged much of the gap through stealth tax increases: a rise in VAT and National Insurance as well as a host of other sleights of hand such as a new set of dividend tax rates and the reform of the Stamp Duty Land Tax.

Not all of these tax rises are necessarily bad. Some, such as increases in VAT, are known to be regressive: the poorest bear the greatest burden whenever politicians put VAT up. Yet I can't find myself getting angry about a restriction on the amount of corporate interest payments that can be offset against corporation tax liability.

Along with the regressive nature of some stealth taxes, the other problem with the addiction politicians have to them is that they undermine open politics. Rather than being candid with people and making the case for fair taxes to pay for decent services, politicians (and Osborne is far from the only one to do this) have got into the habit of infantilising us out of an exaggerated fear of an anti-tax backlash.

Of course, this fear isn't entirely unwarranted. The press is famously good at finding a fictional "Labour tax bombshell" in the lead up to every general election. However, the public doesn't appear to be as conservative about these matters as politicians tend invariably to assume: according to a poll by YouGov taken earlier this year, there is broad support for an increase in income tax to pay for improved NHS care. This appears to have been the case for several years now – a poll from 2014 found a similarly open-minded stance on the part of most people.

Thus, while it would probably be too much to expect a Tory chancellor to stand up on Wednesday and set out a frank and honest case for tax increases, there does appear to be some scope for politicians of the left to be upfront in saying that a civilised society costs money.

As things stand, the steady torrent of stealth taxes takes the public for fools; and if there is a lesson to be taken from the past 12 months, it is that treating people as fools is a political strategy with a limited shelf life.

James Bloodworth is former editor of Left Foot Forward, one of the UK's top political blogs, and the author of The Myth of Meritocracy.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.