Successful 2,300-Year-Old Brain Surgery Techniques Now Being Recreated in Siberia

Russian scientists, anthropologists, archaeologists and neurosurgeons are trying to recreate 2,300-year-old brain surgery techniques after discovering skulls on the Altai Mountains in Siberia belonging to the ancient Pazyryk nomadic tribe.

The Pazyryk people were first mentioned by the Greek historian Herodotus in the 5th century BC. Their mummies have been found preserved in permafrost at an altitude of 2,500m in the Altai Mountains, together with belongings and some of the best ancient tattoos ever seen in the world.

According to the Siberian Times, archaeologists have discovered two ancient skulls that show clear evidence of recovery after undergoing a process called "trepanation".

Trepanation is a highly risky ancient medical treatment given to people suffering from head trauma, where a hole is drilled or surgically scraped into a human skull to treat problems, in particular to relieve cranial pressure when the brain swells due to a fall or other disease, although it may also have been mistakenly used to treat nervous system problems.

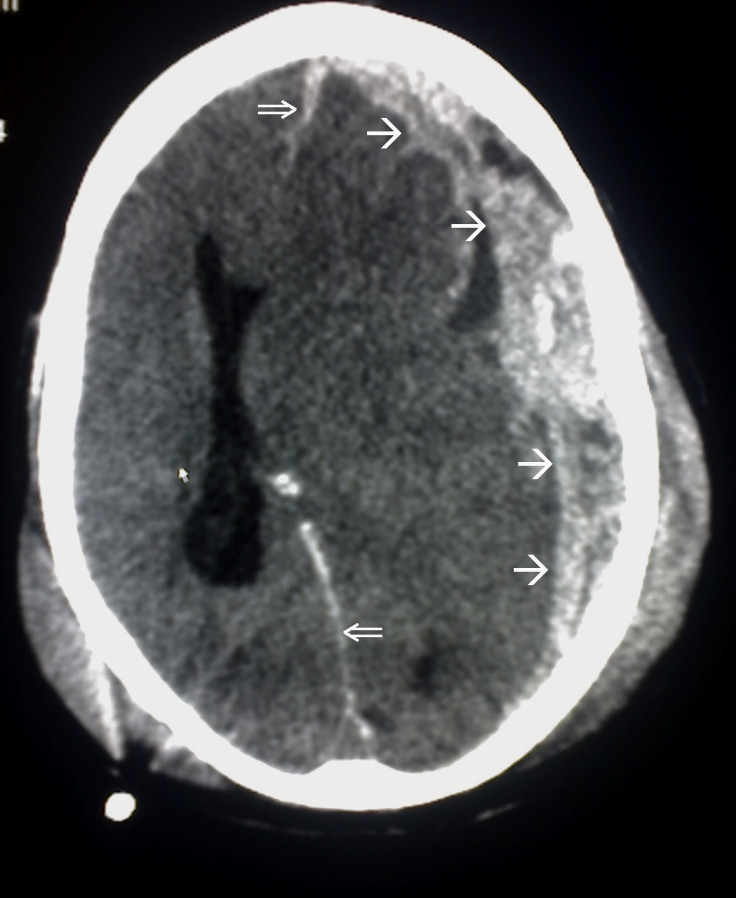

Today, trepanation is still used, but is reserved as a treatment for epidural and subdural hematomas, or for eye surgery like corneal transplants.

"In the middle 19th century, the survival of patients after trepanation in the best hospitals in Europe rarely exceed 10%, which was associated with an extremely high risk of infectious complications, and this operation was committed only when patients had very severe traumatic brain injury," academics from the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the Siberian Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences told the newspaper.

"Even today, with advanced neurosurgical techniques, successful implementation of trepanation requires the serious knowledge and training, and the procedure itself is not considered as absolutely harmless."

Ancient brain surgeries

In one case, the skull of a man who lived to the age of between 40-45 showed that he had suffered from head trauma to his left temporal and parietal bones and developed a subdural haematoma, where blood collects between the skull and the surface of the brain.

A small hole had been carefully made in the skull in a place that carefully avoided causing any further head injuries, about 1cm behind the cranial suture, which is an appropriate distance from the edge of the sagittal sinus, so the doctor clearly had a lot of knowledge about the structure of the brain and where to operate.

From the evidence of later bone growth in the man's skull, it is clear that he went on to live for many years after the surgery.

The other skull of a man meanwhile, showed evidence of a congenital defect from birth that an ancient surgeon had put right by drilling a hole.

The scientists think that the Pazyryk tribe may have had knowledge of the Hippocratic Corpus, a set of about 60 ancient Greek medical texts associated with the physician Hippocrates. The Pazyryk doctor's surgical work seems to be in strict accordance with Hippocrates' treatises.

Recreating ancient surgical tools

The researchers have now scanned the two ancient skulls into a computer together with a third skull found of a woman, who they believe died from a botched trepanning brain surgery from around the same time period.

In almost all graves found in the Altai Mountains, people were buried together with bronze knives, which were clearly a vital tool in their lives.

The researchers have found traces of bronze in mass spectral analysis and X-ray fluorescence studies of the skull bone samples.

From looking at data about the way the holes were cut into the three skulls, neurosurgeons from the Federal Neurosurgical Centre in Novosibirsk are now working to recreate the surgical implements the ancient Pazyryk doctors might have used, and will attempt to replicate their brain surgeries on cadavers.

"Pazyryk culture did not leave any written sources, and that is why it is hard to understand clearly the motives of making such complicated surgery and the methods which were used by doctors," the researchers said.

"Modern neurosurgeons are sure that the manipulations of the head obviously were medical, not ritual, and were carried out by specialists who has some knowledge about the structure of the human body and its diseases."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.