Berlin Wall 25th Anniversary: Inside the Stasi's Paranoid Surveillance State

Cliewe Juritza knew at 14-years-old that he wanted to leave East Germany, known as the German Democratic Republic. He knew that over the wall in West Berlin lay a different German society, one free from the ironfisted grip of Soviet Union tyranny.

"I couldn't imagine spending my life in a fenced-in country. Every day I was able to watch West German television and by that, able to see a whole different world. With colours, with a different society, where people were free to go and do what they wanted," Juritza, born in East Berlin in 1966, tells IBTimes UK.

"In the GDR, you could see that your abilities were not determining what you were able to work or study.

"When I was 14, I applied at the GDR merchant fleet. I wanted to explore the world and that seemed a good possibility. I had good grades at school, did much effort on the application, had a health check. Everything was alright. And still I was denied. Reason: I had a grandmother who lived in West Germany.

"I was so angry, that I took my small bike and tried to bike on the Autobahn all the way to Rostock to complain. Of course, the police grabbed me from the road only a few kilometres from home. But that was the day I decided to leave the GDR."

Berlin Wall

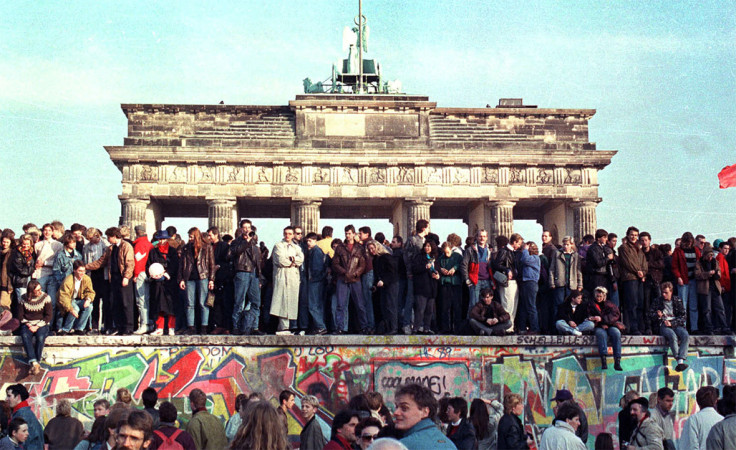

It's 25 years since the Berlin Wall fell and crushed communist GDR. Almost overnight, fearsome East German state institutions tumbled. And the biggest casualty was the Stasi.

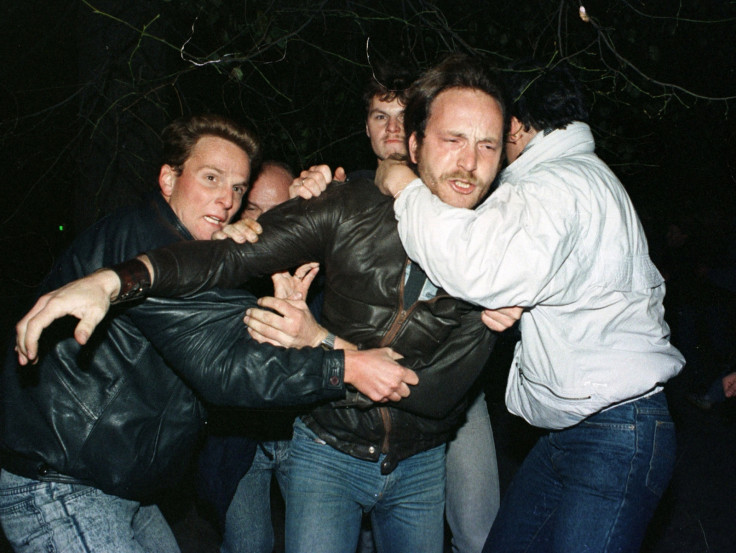

Its network of buildings were ransacked by jubilant protestors as Stasi officials shredded and burned their way through several decades' worth of intelligence files. The only thing that stopped a complete annihilation of documents was the fizzing out of tired paper shredding machines; the consequence of Soviet manufacturing standards.

They wanted to protect informants, hide government crimes and cleanse the archives of any evidence that may be used against them by a vengeful and long oppressed public.

The Stasi was the sensorial element of the East German government, which was propped up economically, politically and militarily by the Soviet Union, its de facto parent state.

Founded soon after the end of WWII, the Stasi was modelled on the brutal Russian secret police, the Cheka. From 1957 until 1989, the Stasi's most active years, it was overseen by the psychopathic head of the Ministry for State Security, Erich Mielke.

The ministry was headquartered in Berlin, from where Mielke ruled the Stasi. There were 15 district offices across East Germany which reported into Mielke, and below them scores more regional offices.

It had departments of investigators and legal experts churned out from internal schools and ran a network of sinister prisons separate to those of the ordinary East German police. It was its own semi-autonomous super agency.

The Stasi's purpose was to see and hear everything in society. Every detail, every piece of minutiae. Documented, scrutinised, catalogued. All of it potential evidence to be used against counter-revolutionaries and dissidents. Its motto was "Schild und Schwert der Partei": the shield and the sword of the party.

Subtleties of language from a tapped phone conversation could be used by Stasi interrogators to extract 'confessions' from those accused of standing in opposition – even if only in their private thoughts – to the state.

This desire for a sprawling and intimate knowledge of everyone came from the paranoia inherent to totalitarian states.

At the heart of totalitarianism is the need for total control. Blind spots in society are a threat to the state's dominance because they are areas in which dissent can grow. It was a truth understood by George Orwell when he wrote 1984, the ultimate story of totalitarian hell.

"The Stasi was informed by history, both its own and that of its Big Brother, the KGB," says Professor Gary Bruce of the University of Waterloo, an expert on modern German history and author of The Firm: The Inside Story of the Stasi.

"The Bolsheviks were a conspiracy that came to power. The thought that there was another group of plotters aiming to come to power just as they did was never far from [the Stasi's] thoughts.

"The uprising of June 1953 also had a profound effect on the Stasi. Caught off guard by the demonstrations that occurred in over 700 towns in East Germany, involving more than one million people, the Stasi was thoroughly embarrassed and took steps to try to avoid a recurrence."

The Stasi was powered by paranoia. Not just its own internalised paranoia, but the externalised paranoia between citizens, friends and families fostered by a surveillance structure that relied on people informing on one another regardless of personal loyalties. Loyalty to the state trumped all else.

By the time the Stasi met its end, it had 97,000 officers marshalling 173,000 informants. But that that latter figures does not include the casual informants, those who just dropped in to tell on a neighbour without being on the Stasi's official roster of gossips.

The scale of the reach of prying fingers is highlighted by Anna Funder in her book Stasiland, a narrative account of those who were, or suffered at the hands of, the Stasi.

Hitler's Gestapo had one agent for every 2,000 citizens. Stalin had one KGB agent for every 5,830 citizens.

"In the GDR, there was one Stasi officer or informant for every 63 people. If part time informers are included, some estimates have the ratio as high as one informer for every 6.5 citizens," Funder wrote.

Den of the Imperalistic Lion

Before he reached adulthood, Juritza was already a big blip on the radar of the East German secret police.

Having seen skateboards in Western television shows and films, Juritza – as any 12-year-old would – wanted one. But they weren't freely available in the GDR.

"I went to the US embassy at Neustädtische Kirchstrasse, went in – today impossible in any US embassy – and I asked the people there if they could at least help me to get a poster of someone on a skateboard.

"Of course, they couldn't and made me leave the embassy. When I came out, some 'gentlemen' came from a building across the street and took me for an interrogation. 'What I had to do in the den of the imperialistic lion,' I was asked: my first interrogation by the Stasi."

Later on at school, Juritza wrote an essay on the "imperialistic protection barrier" – aka the Berlin Wall – and got into trouble for his conclusion.

"I wrote everything I had learned in school about the 'imperialistic protection barrier'. That it was necessary because the acts of sabotage from the West (I couldn't remember any) and made the final conclusion, that the barrier was not necessary any more in the beginning of the 1980s.

"The next days I had to go to the director, listen to preaching about imperialism and stand in front of the class and revoke from my essay."

After these three incidents, "the countless hours I had been running around in East Berlin to buy comic books (Mosaik) [and] trousers" and "the embarrassing fact that we had to wait for parcels from our West German grandmother to have nice chocolate, oranges and coffee", Juritza made his first – and fateful – attempt to escape from GDR.

These wouldn't be the last times Juritza would clash with the Stasi state.

Report everything

Bread and butter intelligence for the Stasi came from its enormous network of informants.

"The Stasi encouraged informants to report any and all information, regardless of how trivial it might appear to the informant. The Stasi would determine what was relevant," Bruce tells IBTimes UK.

These informants came from all areas of society, even those in professions centred on trust. You could trust nobody in East Germany, not your family, not your friends. Especially not your teachers, as one boy's story in Bruce's The Firm attests.

Franz Lehmann was in a German culture class and asked by his teacher, along with his classmates, to draw a picture of the "Future City".

"With coloured pencils, Lehmann, a mediocre artist, drew three city streets heading off to the horizon that ended in front of three clearly labelled buildings: a prison, a bordello, and a nuclear power plant," wrote Bruce.

"This negative view of the future was even more suspicious to the teacher because draped across all three streets was a banner that read: 'FC Union, German Champion', even though Berlin Dynamo FC was the soccer team of choice for the party.

"The teacher insisted that the student drawn another, more proper, vision of the future. This time the cityscape was dominated by prisons and large piles of trash. After having gone to the Stasi's local office to inform them of the incident, the school principal was told that the teaching body should continue as usual. The Stasi would handle the case."

Eventually the Stasi spoke with Lehmann's teacher and the party secretary at the school. In building their profile of the child, the Stasi found he was a punk who watched West German television, didn't have many friends, and idolised his father who opposed the regime. So the agency intervened.

After being locked up for an unnamed offence, Lehmann was approached by the Stasi and signed up as an informant. They focused often on recruiting oppositional people as a means of neutering any threat by absorbing them into the system's gut.

For others, the informants were closer to home.

Vera Lengsfeld is a former member of the post-unification Bundestag. But before the Wall fell, she had lived in East Germany as a civil rights activist and lecturer, before being deported to England. Lengsfield had been imprisoned, interrogated and tortured including being waterboarded, which simulates drowning over her opposition to the government.

But the allegations fired at her by Stasi agents came mostly from comments made behind closed doors, in private spaces. So how did they know? By bugging her house, a common Stasi spying trait? Or intercepting her post?

The truth, she discovered after the Berlin Wall came down, was worse: her husband had been informing on her. She soon divorced Knud Wollenberger.

Lengsfield, who now gives tours of the former Stasi prison Hohenschoenhausen in Berlin in which she was held, told an interviewer from The Daily Beast that she does it "to teach the truth about East Germany, especially to the young".

And the truth about what happened often in Stasi prisons is unsettling. When someone entered the Stasi prison system, it was likely they'd be interrogated and tortured. Beatings, sleep-deprivation, waterboarding – all were commonplace within the concrete walls of a Stasi cell.

One of the most disturbing practices of the Stasi was forced adoption. They would remove and rehome the children of people they deemed politically inappropriate. This could range from outright opposition to the state to acting in a way not seen to fit with socialism.

There are thought to have been 1,000 cases of forced adoption in the GDR and many people are still searching for lost children and parents, their lives stolen by the Stasi. Today, Behr's runs an organisation dedicated to reuniting these broken families.

Go West

After his ill-fated escape attempt, Juritza was held on remand at Rummelsburg prison for three months in a cramped cell with lots of other inmates, among them convicted murderers.

"I had problems in the cell with other inmates. Some of them were brutal and there was no privacy at all," he says. "It is hard to use the WC when people you don't know and trust are watching you."

There was no contact with his family or friends. He later discovered in 2009, after accessing his Stasi files, letters from relatives were intercepted and not delivered.

It is hard to use the WC when people you don’t know and trust are watching you.

After he was convicted, he was sent to Halle. Finally, he was allowed a visit from his mother and sister. Juritza had applied to leave the GDR. On occasion, applications to leave would be granted. But only after a long, drawn out process and often after years of incarceration.

Juritza's sister told him his application to leave had been rejected. He was furious and shouted that he would once again try to escape when he was out of prison. The guards came over and bent his arms back with a chain to restrain him. He was sentenced to a week in isolation.

"The cell was awful. Not because of the isolation, but because the WC was behind bars. I had to ring a bell if I needed to use it."

He was also afraid that his sentence would be extended. It was not. Still in prison, he again applied to leave the GDR for West Germany.

While working in prison manufacturing light bulbs, Juritza was suddenly take by a guard and told to pack up his belongings. He was transported to another prison, Karl Marx Stadt, sometimes used as a holding place for GDR citizens about to be sent to the West. Juritza got his hopes up. He sent a postcard to his sister, a code indicating he was about to leave the country.

"One morning I had to climb into a Western bus, with many other prisoners. We travelled in the direction of the border," he said.

"All was quiet in the bus. We all had had the same lawyer, Wolfgang Vogel, who was negotiating the release against money for the GDR with West Germany. Vogel held a speech and left the bus at Marienborn. Then we really drove across the border. When we were in the West there was a big applause."

The new citizens of the west were taken to Auffanglager Gießen, a "special refugee camp for released/escaped GDR people".

"There we were welcomed, got a little money, new clothing and we were all interrogated by all three western allies. The GDR used this release programme to smuggle spies to the West, so everybody was questioned.

"My questioning didn't last very long and I had a new destination: my grandmother, who lived only a few kilometres from Gießen, in the medieval town of Hannoversch Münden, where I wanted to start a new life."

Romanian vacation

Some of what the Stasi did was horrifying. Some of it was plain absurd.

Empty jars of 'smell samples' were swabbed from worn clothing, often underwear, by Stasi officers sent to break into people's homes. These, thought the Stasi, could be used by sniffer dogs to suss out who had been in a room, perhaps the location of a suspicious meeting.

In a training video for Stasi trainees, one young male officer is dressed up as an old woman and sent out into central Berlin to look inconspicuous. The message from this surreal instructional film is clear: suspect everyone and trust noone. Even elderly ladies can be counter-revolutionaries.

Bruce recalls one of the stranger stories he had encountered in his research. The Stasi arrested a highly respected chief surgeon of a local hospital and his wife at the East Berlin airport, just as they were heading on holiday to Romania. But the Stasi didn't care about his standing. They thought he would flee to the West, which was unacceptable.

"The surgeon and his wife were dragged through the airport into an awaiting Stasi van and brought downtown East Berlin where they were interrogated," Bruce says.

"They were then transported in the middle of the night to Schwerin, a city in the north. The Stasi held a gun at the surgeon as he relieved himself in a bush at the side of the road. The couple was released in the early morning hours.

"The next day, the Stasi appeared at his office and paid him, down to the penny, for the Romanian vacation they had forced him to forego. They then asked him to be an informant. Considering what he had seen of the Stasi's power, he felt he had no choice but to agree.

"From what we now know, it appears that the whole episode was an elaborate ruse to turn the surgeon into an informant; the Stasi never really suspected he was leaving for the West."

After reunification

Work to repair the millions of fragments of paper – secret files, documents, memos – hastily shredded in the final moments of Stasi control is still ongoing. In Berlin alone, there were 15,500 bags containing as many as 80,000 fragments each to be sifted through and put back together.

Thousands of people are still accessing their files to find out who knew what and when. And, perhaps most importantly, who was informing on them.

After German reunification in 1990, many of the senior Stasi officials were prosecuted for crimes committed in the GDR. But many were not. They went on to become members of the German parliament, take roles in the security and police services, or faded into obscurity.

There is even The Society for Legal and Humanitarian Support, a group for disgruntled ex-Stasi officers struggling to cope with reunification. It has been known to protest against the way the Stasi is portrayed in museums and the media.

Bruce says the vast majority of Stasi officers believed that they were on the right side of history.

"The officers from the earlier years of the regime, like the long-serving Minister of State Security Erich Mielke, were drawn from the ranks of revolutionaries, those Communists who had been in street battles with the Nazi. By the end of the regime, the Stasi had become a family affair," he says.

"Many officers were sons (over 90% of officers were men) of other officers. Although they didn't necessarily have the revolutionary zeal of the earlier cohort, they still believed in the cause

"Without question there are former Stasi officers who have no regrets. I would say this describes the majority of them. And they take delight in increased surveillance by western governments on their own populations in the name of national security, claiming that they did no different.

"There are Stasi 'alumni' networks ... They have been known to disrupt public meetings related to the Stasi past, such as book launches, but this has not occurred for some time now."

In Stasiland, Funder notes that former Stasi "still meet in groups, according to rank, or at birthdays and funerals". One seventieth birthday party of a former officer was "run like a divisional meeting from the old days. There was an agenda and the men went through it item by item."

Bitter

Juritza, who now gives tours of Berlin and tells his story of life on either side of the Iron Curtain, is even-minded on whether or not justice was served on the Stasi after the wall came down.

"There is a juridical and a moral side to that question. Like Bärbel Bohley said: 'Wir wollten Gerechtigkeit und bekamen den Rechtsstaat'. We wanted justice but got democratic legislation. I am not sure about this translation. In my opinion there is no better way to say it.

"The revolution/fall of the Wall was a peaceful one. One of the rules of a constitutional democracy is: no retroactivity. You cannot punish a person at a later point in time for deeds that were legal at the moment he/she did those deeds.

"It is right, that those who fired excessively at the Berlin Wall/inner German border or gave the order to shoot, were punished and had to spent time in prison. But as always, that doesn't bring a dead person back."

What is unambiguously awful is that those who suffered so much under the Stasi are still often worse off than the perpetrators of the system, many of who have prospered - and have even been elected.

"It is awful, that former Stasi people are sometimes far better off than those who have suffered under their regime, because they were not allowed to study or do the jobs they wanted, because they suffered trauma from time in prison," he says.

"And the Stasi people working as lawyers, psychologist, having high jobs and high pensions. And the 'victims' having low pensions, because of the low jobs they had or because they are not able to work at all."

What Juritza wanted is for the Stasi to stand up and say: we were wrong. He wanted openness, discussion and dissection, like the South African truth commission after apartheid.

"It is surprising how fast the human brain seems to forget, how people can say 'in GDR times we were so closely together, showing solidarity'," he says.

"We had to share, trade, interchange everything because you could not buy it, not because we liked each other so much more than today.

"What is also surprising is, that the idea of communism is not dead after all these years of suffering in Eastern Europe, after the millions of dead people under Stalin's regime.

"The idea of a fair world, where we all share and happy seems to be too promising. I guess, the idea that we are all equal lets people forget that there will always be some that - at least think that they - are more equal than others.

"It is bitter to see that. That people elect them, even more."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.