Brussels attacks: How Belgium became Europe's cockpit of Islamist terror

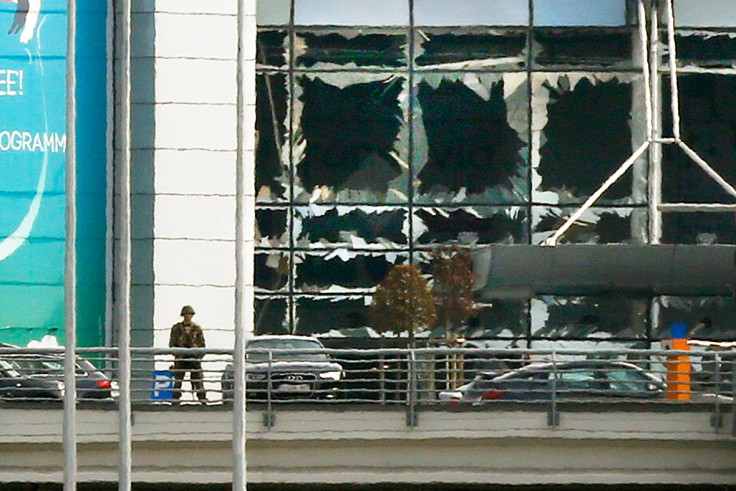

As the dust settles on the dual bombings in Brussels on Tuesday morning, questions are already being asked about the ability of the European city to deal with what appears to be a terrorist epidemic. Just days after Salah Abdeslam, the architect of the Paris attacks, was tracked down to the suburb of Molenbeek, a suspected suicide bombing hit Brussel's airport and a second bomb exploded on the city's metro network.

Follow IBTimes UK's live coverage of the March 22 Paris attacks here.

It is not the first time that Molenbeek has made headlines. Abdeslam and his brother, Ibrahim, lived there prior to the attacks and it has long had a salubrious reputation as a hotbed of Islamist extremism and radicalisation. Molenbeek was also linked to both the Charlie Hebdo attacks, the Thayls train shooting, and the 2014 murder of four people outside a Jewish museum in Brussels.

And it not just the rough suburb that has been in the spotlight, but Belgium itself. Across the country at least 380 people have travelled to Syria giving the country the largest number of jihadists per capita, at 33.9 fighters per one million residents. Now it seems that not only can terrorists such as Abdeslam hide out in Brussels for several months avoiding a Europe-wide manhunt, but militants can bring yet more chaos to the city's streets.

Once termed the "cockpit of Europe" due to the large number of grand European battles fought inside its borders throughout history, Belgium has now become the breeding ground for the seditious form of modern terrorism that has been hitting Europe over the past two years.

While it's not yet clear the background or motivation of the attackers in Brussels on 22 March, reports have surfaced that prior to one attack shouts were heard in Arabic. It has been confirmed that the airport bombing was a suicide attack – very much the modus operandi of terrorist organisations such as Islamic State (Isis). If it turns out to be another attack inspired by Daesh, then Belgium's problem with militant Islam is bound to come to the fore.

Muslims in Belgium make up 6% of the population, second only to France which stands at 7.5%, and that has doubled since 2005. Unlike earlier waves of immigration from Morocco and Algeria, which was encouraged by the authorities in the 1960s and 1970s to supplement the native labour force, recent immigrants have traditionally been families re-uniting or asylum claimants.

A recent report by the International Institute for Counter Terrorism highlighted the significant social issues facing Belgium and the disproportionate affect that they have on the country's Muslim community. It cited high levels of unemployment, high levels of discrimination, low educational achievement, poor integration and inconsistent governmental funding pervasive among the Belgian Muslim community.

"These poor demographic realities of the Belgian Muslim community might be significant in providing a fertile ground for radical Islamic parties and organisations to recruit," the report's author, Sarah Teich, said.

Belgium has put 160 people on the international wanted list, some of which have been tried in absentia and others suspected of having left the country to fight in Syria. One of its most infamous militants in recent years was Abdelhamid Abaaoud, the ringleader of the Paris attacks; a dual Belgian and Moroccan national who fell into IS circles and later fought in Syria after a life of petty crime.

Belgium's foreign minister, Didier Reynders, said on 20 March that Abdeslam had told investigators he was planning a fresh attack in the capital, the Guardian reported. "He was ready to restart something in Brussels, and it may be the reality because we have found a lot of weapons, heavy weapons, in the first investigations and we have found a new network around him in Brussels," Reynders said.

The IICT report cited statistics suggesting foreign-born Belgian residents have unemployment rates more than twice that of native-born Belgian citizens, a burden that falls on neighbourhoods such as Molenbeek. Other studies, it said, point to systemic discrimination as an operating cause of low foreign-born employment and evidence that job applications are often rejected based on Muslim names. Only 12% of Muslims (compared to 23% of non-Muslims) hold high educational achievement, it revealed.

Much of that is a failure on the part of previous governments to prepare for the long-term population growth that came with the labour reforms of the 1970s. It added: "At the very beginning, Belgian authorities believed that the foreign workers would come to Belgium, do their work, and return to their home country. Consequently, there was a noticeable lack of preparation, program, or means of integration," Teich wrote.

But while there will be questions about why Belgium was not ready for another attack this week, the authorities have been cracking down on extremist groups since the emergence of Daesh in 2014 and last year's Paris attacks. In February 2015, a criminal court ruled that Sharia4Belgium, a group believed to have helped funnel fighters to IS, was a terrorist organisation and sentenced its leader, Fouad Belkacem, to 12 years in prison.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.