Building a cloud in space – this IT company is taking the space industry into the 21st century

A Finnish IT company is offering cheaper access to space by building and programming its own satellites.

Want to go to space? Maybe you should consult the computer nerds. A Finnish IT company is turning the space industry on its head by offering tiny low-cost satellites with loads of use cases that can be easily automated and controlled back on Earth.

Helsinki-based Reaktor is an IT and engineering company that focuses on creating bespoke solutions to fix problems in other industries, so rather than selling one standardised IT system and expecting people in different industries to just use it regardless, the firm will come see what problems you encounter and instead code software to fix them.

Reaktor says its customers wanted to have their own satellites for a wide range of reasons including detecting oil spills, monitoring crops, detecting deforestation and reducing traffic congestion, but when the firm tried to integrate its software with existing satellites, it found that the process was far too complicated.

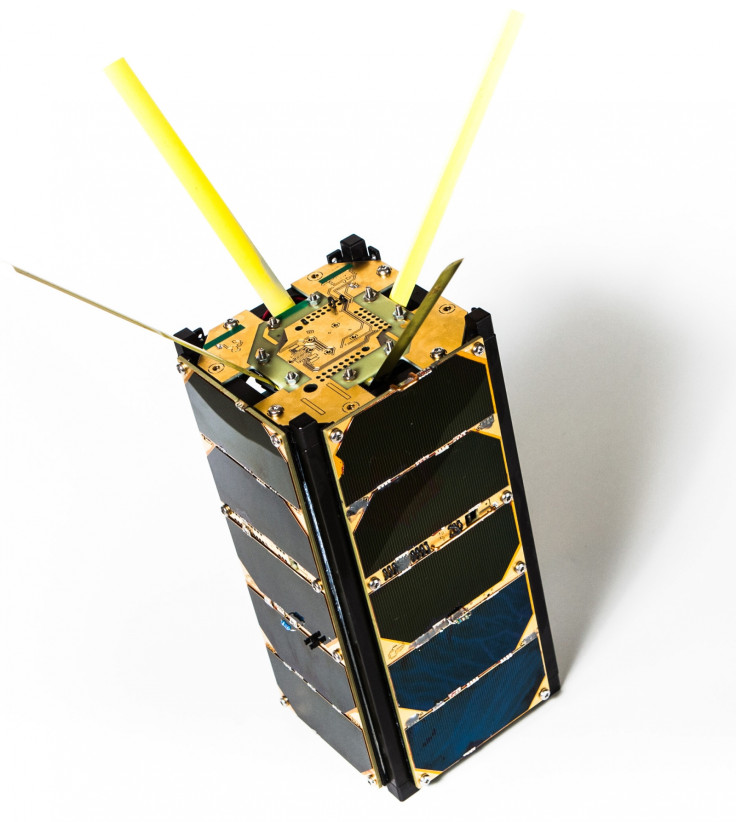

So in the end, Reaktor decided to just build its own satellites, especially with the advent of "cubesats", which are tiny low-cost miniature satellites typically used for space research.

Space industry software is currently way too complicated

"We didn't really expect it to go like this, but it turns out the space industry is lagging behind in terms of their software," Juha-Matti Liukkonen, Reaktor's director of space and robotics told IBTimes UK at the Slush 2016 tech conference in Helsinki.

For the first and second generations of our cubesats, we did it the way the traditional space industry does it. It's quite slow and expensive, and it forces you to do the software in a quite a complicated and error-prone way,

"I'm a software developer and I have been developing embedded systems for telecoms, robots, cars and aeroplanes for over 20 years. I developed the theory that 90% of everything is essentially the same, only 10% is domain specific. Basically, we discovered that the processors, communication protocols and software platforms were the same as what we had been using in the automobile industry many years ago for robots."

Coincidentally, satellite space researchers at Aalto University had been developing their own tiny cubesats since 2010, so in 2015 the research was spun off as a startup which joined Reaktor as its space arm to provide the hardware that the firm could then programme to work using its software.

"For the first and second generations of our cubesats, we did it the way the traditional space industry does it. It's quite slow and expensive, and it forces you to do the software in a quite a complicated and error-prone way," explained Liukkonen.

"We're not doing satellites because we want to do space technology or compete with the existing space industry, we're doing small and cheap sensor boxes to feed data to the IT systems that run our customers' businesses to solve problems."

A plug and play satellite, just like Lego

So for the third generation of the cubesat – the Reaktor Hello World – the Reaktor space lab decided to try something different and use modular design instead, where components on the satellite can easily be swapped out and fit together without causing a big headache.

"[Apart from] the batteries and power input from solar panels, a satellite always includes a part that handles the flight control. We have built that part in such a way that we can use the same part in different sized satellites for different applications. It's like a Lego block. Traditionally, the satellite has been custom-built for every use case, but with our cubesat, we can plug and play every part of the satellite," said Liukkonen.

"The Hello World cubesat has the flight platform and the payload part. The payload part has the hyperspectral camera and this can be used to detect dozens of different types of substances. We expect this exact payload to be another Lego block, so we can solve many use cases with this same configuration."

Launching a satellite into space is hugely expensive, and so is renting space on someone else's satellites, so if you just wanted to monitor something very specific, similar to scientific satellites, then a cubesat would suffice.

But Reaktor wants to bring the costs down even further. Cubesats typically weigh between 2-5kg each, and to launch it into space, the going rate is €50,000- €70,000 per kilogram, so if you had a 5kg cubesat loaded with different censors, each one would set you back by €350,000. Apart from being modular, the cubesat is also lighter and weighs just 2.2kg, which means launching it into space costs only €130,000.

Going into orbit in 2017

Reaktor has now developed three generations of cubesats, but sadly none of them have yet gone into space, because the first and second generation satellites were both slated to go on SpaceX rocket launches in 2015 and 2016 that were cancelled due to the two SpaceX rocket explosions.

The first generation cubesat is now slated to go up in a SpaceX rocket in January 2017, followed by the second generation cubesat containing scientific instruments, which will be sent into orbit in March 2017 as part of the QB50 European Commission-approved project to improve access to space by launching a network of 50 small space satellites to research the Earth's atmosphere, and finally the Hello World cubesat will head into space from India in April, launched by the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO).

The QB50 satellites will be sent to the International Space Station (ISS) to be launched by the astronaut crew stationed there. The data received by the 50 satellites will be sent back to 85 universities across Europe, and the Reaktor satellite will beam information about the upper atmosphere down to Aalto University.

2017 will be a big year for cubesats, and Liukkonen, who is an avid space fan, also has a challenge for the community of inventors, scientists, engineers and enthusiasts keen on the controversial space propulsion technology EmDrive.

"I've read the Nasa paper and it seems to work, but if somebody would build a cubesat-sized EmDrive, I would absolutely fly it, and then we would know if it actually works in real conditions or not," he said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.