Burundi: Exiled activist Pamela Kazekare launches Komezamahoro political movement amid worsening violence

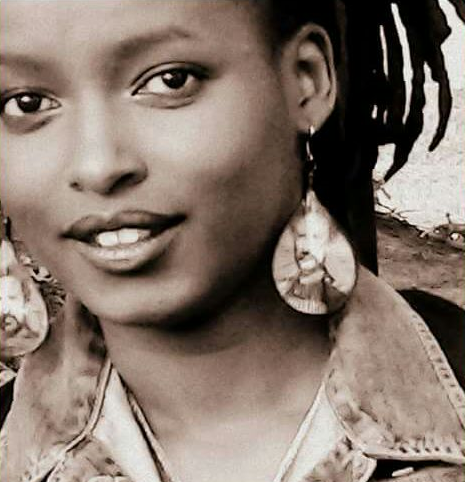

A former TV presenter and exiled Burundian activist has launched a new political movement as at least six people were murdered since Sunday (2 July) amid deepening violence in the country. Pamela Kazekare, a former cultural activist and journalist at the Radio Publique Africaine (RPA) in Burundi and the Antenne Centre Télévision, a Belgian regional TV channel where she was the first black woman to present the news in Belgium, has launched a new political movement named Komezamahoro.

Komezamahoro, a new political movement

The movement is named after 15-year-old Jean-Nepo Komezamahoro, the first victim of the street violence that has killed more than 100 since 26 April 2015, when President Pierre Nkurunziza announced that he would stand for a third term.

Kazekare was deeply involved in organising protests, such as the 13 May Women's march and assisting protesters. Yet, she deplores the lack of participation of the political parties, who had called for the demonstrations, when it came to feeding, treating and helping protesters and those injured.

Following a severe crackdown by the authorities on protesters against the third term and fearing for her life, Kazekare fled to neighbouring Rwanda.

"In Rwanda, I tried to learn from the past months and think about our lack of involvement (in leading political change) and the consequences of it on our future," she told IBTimes UK in an interview in the capital Kigali.

"If those who were organising the protests had used what was available for them in this current world, such as smartphones and worldwide connections, we would have succeeded. But we were warded off, exploited and sent in the streets to throw stones."

Building Burundi's future

When she arrived in Rwanda, Pamela was faced with young Burundians who had fled Burundi with the intention to join the rebellion and take arms - "basically to re-enact the (civil) war; that I don't want".

"When I saw this, I realised that, even though I enjoyed my time as a cultural activist, it was time to enter politics."

Having grown up during Burundi's ethnic and civil war (1993-2005), Kazekare said she hopes for a change from the "old politics" - politicians in government and opposition parties, who she claims live in the past.

"This time, we realise our strength: we were the ones in the streets, we were the ones taking care of our brothers who were injured and now, we are saying 'No More'. You, the old generation, have produced politics and results that we do not relate to. We're not Hutu, or Tutsi, or Twa. The old generation that is negotiating today can stay to tell us what happened in those days (of civil war), but they shouldn't participate in the construction of our future," Kazekare said.

"I want to sit down with these politicians and be there when they decide about Burundi's future because I don't want those people, who were incapable of participating in the demonstrations that they had had a year to prepare and called for, to run my country. It would be an insult to Burundians' intelligence and we can do better than that."

Political intelligentsia movement

The movement, based on the concept of political intelligentsia - a group of well-educated people who guide the political, artistic, or social development of their society - relies on five pillars: integrative intelligentsia, Gira-Iteka, accountability, positive citizenship and democratic justice (see box-out below).

"We know that these five pillars, when applied, automatically set out qualities that we want to find in our country," Kazekare explained. "We dream that this new Burundian identity is someone who knows and abides by these pillars, who is part of a savings and credit community and who understands the meaning of work in cooperatives."

While Komezamahoro is still in its infancy, the movement's political program will stem from findings of think tanks, which Kazekare explains will develop, promulgate and produce solutions to address the country's issues in areas such as healthcare, justice, youth and culture.

Kazekare said: "What our movement wants to achieve is to bring together this intelligence in think tanks, which will study these subjects and come up with guidelines to follow. In that way, we'll have a solid political program that we'll be able to defend in the next elections or when we meet our supporters."

An international movement

The movement hopes to capitalise on the Burundian diaspora - hundreds of thousands of people living in exile and refugees. "We are from the smart, global generation, so this movement also touches all the people in exile, like us," said Kazekare.

To spread the word outside of Burundi's borders, Kazekare has in mind to set up a web radio station - independently broadcasting from Burundi is currently forbidden - as well as using mobile caravans.

"The radio, that would bring us together, could help more people discover what their fellow Burundians are doing elsewhere, and could help develop contacts or inspire others to take action. We also want to drive around the country, stop somewhere for however long and explain what we are doing. We are a generation who needs to invent its values - because our parents' values have led us to exile," said Kazekare.

The movement has already found support in a number of Burundian high profile personalities, including humanitarian Maggie Barankitse and artists such as Kaya Free and Christian Ninteretse.

What is the Komezamahoro movement? By Tresor Nyongabo, deputy spokesman

The death of Jean-Nepo Komezamahoro inspired us to launch a new political movement. The opposition parties promised us to be leaders, but we have been disappointed. Young people were being shot but nobody from the political parties came to help or see them. We did everything while the opposition parties were just wearing the medal, our medal.

The movement is based on five pillars:

Integrative intelligentsia: Giving priority to Burundi's elites and meritocracy, to help elaborate new national policies.

Gira-Iteka: 'Iteka' in Kirundi translates as honour, when one recognises the value of another in a society. Exploiting the value of Burundians: we don't want to bow before people who steal from others and have no real value in our society.

With $267.10 GDP per capita, Burundi is the second poorest country in the world, where 80% of the population lives with under $2 a day, but it should take profit from its unexploited richness such as its landscape and workforce - 50.7% of its population is under 18.

Accountability: Obliging the government to be held accountable for any of its action.

Positive citizenship: Teaching and understanding Burundians' rights and obligations in a new Burundi they have to help improve and develop. Burundi has ratified so many conventions related to rights for children, women and minorities, but how many know them?

Democratic justice: Ensuring the judicial system does not take into account one's past, ethnicity or native region, but only the law. We need to break that cycle: who steals should be punished, who kills should be punished.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.