Central American migrants choose Mexico over US, thanks to Donald Trump's policies

The president's hardline immigration policies have resulted in fewer Central American migrants trying to enter the US.

Donald Trump's hardline immigration policies have resulted in fewer Central American migrants trying to enter the US. However, plenty are still fleeing their poor, violent home countries, with many deciding to stay longer in Mexico, which has traditionally been a transit country.

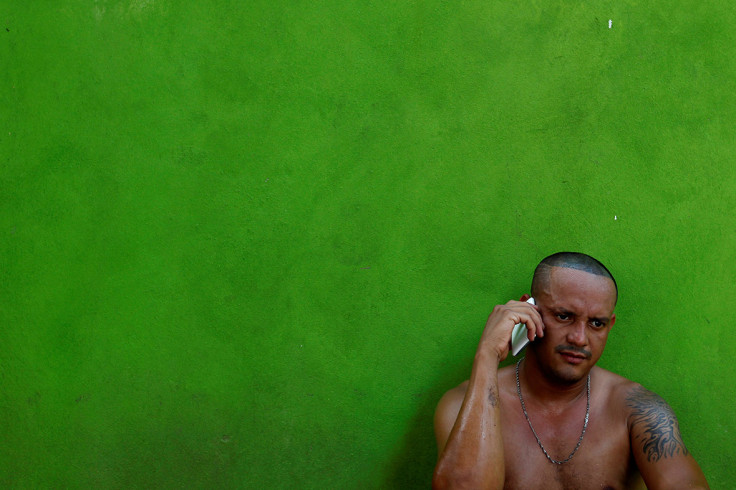

Reuters photographer Carlos Jasso visited a migrant shelter in southern Mexico, near the Guatemalan border, and took portraits of its residents.

Some undocumented migrants have reported that the prices charged by people smugglers had risen sharply since Trump took office, now hovering around $10,000 (£7,715), up from about $6,000 a few years ago. Although many migrants still hold onto the hope of the American dream, Mexico has become the long-term home for many unsure of what a future in the US will hold.

Asylum applications in Mexico had been rising steadily in recent years as the flow of people leaving Central America increased. But in 2016, as Trump campaigned on a tough anti-immigration platform, applicants jumped to 8,781, up from just under 3,500 in 2015.

According to officials, the number of people applying for asylum in Mexico has soared by more than 150 percent since Trump was elected president. Many of those requests were from Central America. Between Trump's election in November and March, 5,421 people applied for asylum in Mexico, up from 2,148 people in the same period a year earlier, Mexican government data shows. Mexico's refugee agency COMAR predicts it could receive more than 22,500 asylum applications in 2017.

The Trump administration has pointed to a sharp decline in immigrant detentions in the first few months of this year as a vindication for the president's immigration policies, which have sent shudders through immigrant communities across the continent.

In the southern Mexican city of Tenosique is a shelter known as The 72, home to many migrants as they ponder the future. Roberto Franco is 55 and travelled overland from Honduras to Mexico. He believes he will eventually make it across as the US economy depends on manual labour from migrants.

Other migrants are aware of the challenges of crossing into the US and still have their sights set on travelling north to send money to their families back home. Despite their concerns, some Central Americans are undeterred and have decided to try their luck at entering the US. If they can't make it, Mexico is the back-up plan for many.

Concepcion Bautista made her way to Mexico from Guatemala with her young son. She still plans to reach the US, but will linger in Mexico to see how Trump's immigration policies play out. Bautista fled Guatemala after gang members threatened to kill her and seized her home, demanding money to give it back. Her ultimate goal is to reunite with her father and two sons up north, but for the time being, she believes applying for asylum in Mexico is smarter than trying to break into Trump's US.

"I'm not going back to Guatemala," the 39-year-old said at the shelter. "I have faith that we'll be able to cross but for now, at least, I'm staying in Mexico."

A 19-year-old pregnant woman from Honduras, who didn't want to be identified, told Reuters: "I have three children back home in Honduras. I was part of a gang. I don't want that anymore, I got shot once in the leg. It's very dangerous to live there. I would like to go to the United States and take my children with me."

Ale, 34, and from Guatemala, lives with her children, Luis and Maria, at the shelter in Tenosique. "We had a small business in Guatemala and gang members used to extort us. We would like to start over in Mexico or in the United States," she said.

With Mexico's immigration authorities controlling migration more assiduously, Central Americans are forced to take more isolated, dangerous routes where the chances of being mugged were higher. In a remote, rocky tract of land near the Guatemalan border, Feliciano del Cid, 60, and two traveling companions were trying to sneak past Mexican immigration officers and avoid being assaulted by gang members on their long trek north.

"We've gone north (to the US) several times, but every time it's got harder," said del Cid, who was deported from the US in December. "(Now,) it's better if we travel alone, along new routes."

Welquin Rivera, 34, and from Honduras, was deported from the US back to his homeland four moths ago. Now he is trying to go back to the States to be reunited with his four children.

Samuel, who used a pseudonym, was threatened with death after gangs kidnapped and murdered his 19-year-old son in El Salvador, prompting him to plan a move with his family to the US. Trump's election changed everything. "I wanted to go to the United States with my family, but we've seen that the new government there has made things harder," said Samuel. "For the time being, we want to stay here in Mexico, and we've already applied for refugee status."

Irrespective of struggles in Mexico and the hard journey north, all of the migrants were certain they did not want to return home. "Only death awaits me there," said Samuel.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.