The elite should beware – a white van and laptop rebellion is underway

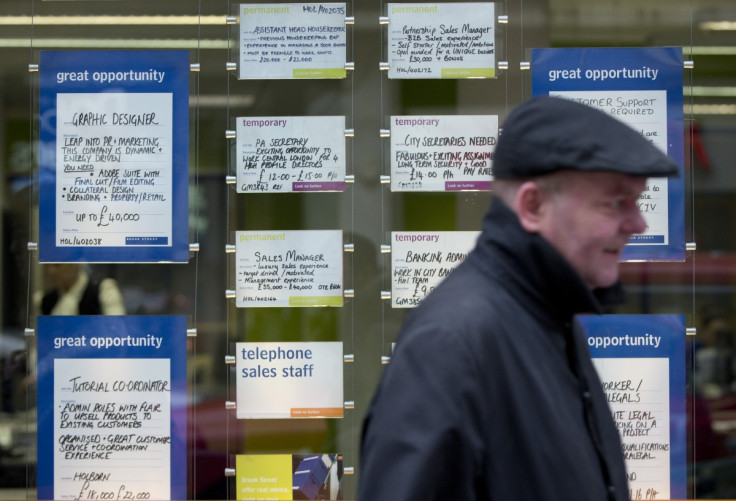

Those running small businesses usually side with the elite. Increasingly, they're doing the opposite.

A surge in small business creation and self-employment since 2008 saved the UK from a depression, and has since driven our economic recovery. Not only that the Centre of Entrepreneurs believes the country is experiencing a fundamental change in the structure of the economy.

There are now over 5.4m small businesses in the UK – 2 million more than 2000 – with 4.1m of them employing just their owners. This means around 15% of the workforce effectively works for itself, the highest rate in both the G7 and the EU. And, with the growth of the 'gig' economy (self-employed people contracted to app-based companies such as Uber and Deliveroo), it's a figure that's set to grow.

Entrepreneurship is therefore the employment phenomenon of the age: a workplace shift as fundamental as the agricultural and industrial revolutions before it. And while the economic consequences seem positive – give or take arguments regarding gig-economy workers' rights – the political fallout could be as disruptive as those earlier revolutions.

Indeed, evidence suggests that the elite, ie. those running capitalism's political-economic structures, should be worried – a laptop and white-van rebellion is underway. We'll come on to the elite, but first let's look at those revolting entrepreneurs.

Like the Peasant's Revolt of 1381, this is a rebellion fermented in Essex. From the 1980s onwards, this individualist county became the spiritual home of white van man – independent tradesmen offering services once sourced from the Yellow Pages. But their success – resulting in an Essex swagger as distinct as those famous orange suntans – has spread across the UK, as well as across genders, age-groups and skills.

Extraordinarily, this change has even reached the graduate sanctums of inner London, as well as other centres such as Brighton, Manchester and Edinburgh. Here, skilled graduates are eschewing formal employment to become freelancers, with over 1.4m people now selling their professional, creative or IT skills to the highest bidder.

Shared-workspace or 'incubators' are springing up, as are desk-n-sofa members' clubs – though café and laptop entrepreneurialism remains the norm. Driven by technology and the desire for work-life flexibility, modern self-employment looks like a lifestyle choice – so why the threat to the establishment? Well it's worth remembering that these are the people Karl Marx identified as the petite bourgeoisie: the highly-productive class of functionaries above the industrialised proletariat but below the 'haute' (or high) bourgeoisie (ie. the political and economic owners of the means of production).

Anti-capitalists such as Marx saw the petite bourgeoisie as the foot solders of an exploitative system – those offered economic security and a chance at advancement in exchange for fealty to the capitalist classes. But the petite bourgeoisie are no longer salaried slaves of the capitalist system. And they eschew the greasy pole. Increasingly, they sell their skills on a contracted freelance basis to the highest bidder.

They're economically liberated, although – with no company pension of job security – it's a freedom tinged with financial vulnerability. And it's this combination of economic independence and financial fragility that's driving the rebellion of the self-employed.

June's Brexit vote is the most obvious example of dissent. Remember, that while most London boroughs voted Remain in the EU referendum, the Essex heartland of Havering (home to Romford Market – a Hajj-worthy Mecca for Essex entrepreneurs) opted overwhelmingly for Leave, as did all of Essex and similar white-van areas such as north Kent.

Indeed, it was probably the Remain camp's inability to understand the changing attitudes of this key demographic that lost it the vote. Yet the clues were there. Prior to the 2015 election, the surge in Ukip support was most pronounced – not in the post-industrial rust belts suffering under the weight of dereliction, a later breakthrough area for Ukip – but in the modern housing estates both north and south of the Thames estuary.

But what of the other end of the entrepreneurial spectrum? What's happening politically in those Hackney railway arches full of freelance designers and IT specialists? Sure, as millennials, they may reject the nativist values simmering away beyond Zone 6, but that doesn't make them followers of the political mainstream.

Far from it, for here resides the "social justice warriors" of the hard-left. Retaining their student idealism, this is the key demographic supporting Jeremy Corbyn's insurgent takeover of the Labour party. To the mainstream's confusion, Corbyn's popularity isn't derived from globalisation's victims, but from its offspring.

Politically, Essex Man and the new urban freelancer are two sides of the same coin. Both represent a rejection of the old political order. Sure, the laptop gang may be closer to the Occupy movement than to Ukip but in both cases it's the elite that's under fire.

And it's a phenomenon with strong echoes in the US. In greater New York – a socio-economic region similar to south-east England – the equivalent of Essex Man famously lives in New Jersey, which was one of the surprise northern states nominating Donald Trump as the Republican candidate.

Meanwhile, the young and free occupants of Brooklyn (New York's Hackney) voted in record numbers for radical socialist Bernie Sanders, despite this being Hilary Clinton's nominal home state. The core of the laptop-n-latte economy went left, not because of the inequalities of deindustrialisation – again, both groups are prosperous – but because both the economic independence and financial fragility of self-employment translates into a rejection of the political mainstream and a detestation of elites.

How the elite responds to this rebellion is anyone's guess – not least because changes within the elite's make-up over the past quarter-century have played a critical role in this fermentation.

Those on the receiving end of this latter-day pitchfork rebellion – Marx's haute bourgeoisie – have become both more international and narrower in experience. While borderless, they emerge from a tiny group of elite universities (Harvard/Oxbridge/INSEAD among them). And while they compete among themselves for all the top jobs in government, business, the media and the third sector, any petite bourgeois expectations of joining their table through guile, diligence and loyalty have all but vanished.

Social mobility is dead and with it the obedience of capitalism's most productive cohort. And this despite the fact Marx's capitalist class no longer possess their key weapon for exploiting the masses – ownership of the means of production.

Nearly all the organisations the elite controls – in business, the media and government – are 'public' (or publicly-listed) entities in one form or another. The elite therefore owns nothing other than the period inner-city properties they buy at inflated prices, while the self-employed are denied a mortgage.

This makes the elite no different to the petite bourgeoisie – except they've awarded themselves the power, privileges and fat salaries of the old capitalist class. They enjoy gold-plated (ie. defined benefit) pensions that accrue wealth without any of the associated risks and are often paid for and guaranteed by the pensionless taxpayer. And they even swap top jobs between themselves – perhaps a political career mixed with a spot of journalism, or a stint in business followed by some politics or life heading a quango or something worthy.

No wonder surveys reveal a hardening of attitudes towards to the elite – something apparent from both ends of the political spectrum and increasingly translating into voting behaviour.

As US commentator Joseph Sobran said: "Politics is the conspiracy of the unproductive but organised against the productive but unorganised". Well those highly-productive self-employed groups are becoming organised – and if the centre ground of British politics is to hold, the elite must heed the warning.

Robert Kelsey is the best-selling author of a series of "anti-self help, self help" books, including What's Stopping You? Get Things Done, and The Outside Edge. The former financial journalist and investment banker is also the deputy chairman of entrepreneurial think tank The Centre for Entrepreneurs which he co-founded.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.