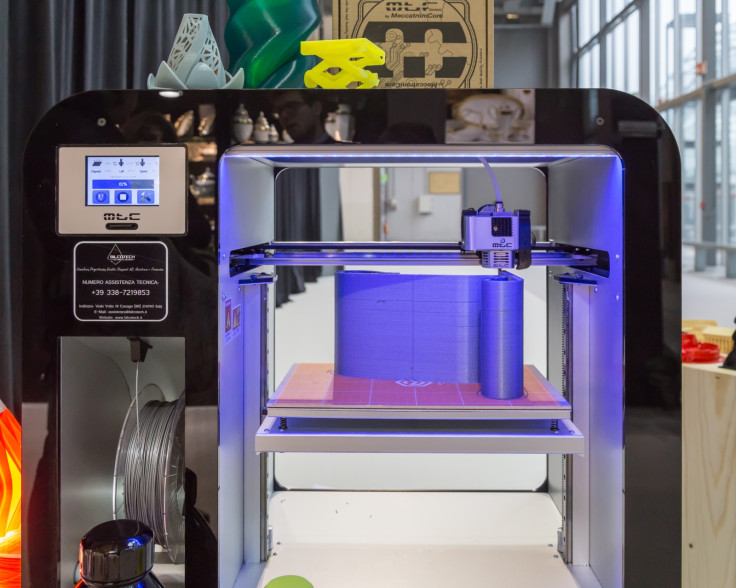

Hackers could potentially introduce 'fine defects' into 3D printed products, NYU researchers find

NYU researchers have found that 3D printing does pose cybersecurity risks during the production process.

In recent years, 3D printing technology has become all the rage in the tech sector, inspiring both experts and ordinary people to produce a seemingly limitless slew of innovative creations, from satellite parts and buildings to prosthetics and even food. As the emerging technology continues to advance and increase in popularity NYU researchers have now found that it does pose some potential cybersecurity risks, specifically during the manufacturing process.

Examining the possible cybersecurity risks and implications of 3D printing technology in a paper titled "Manufacturing and Security Challenges in 3D Printing", a team of materials and cybersecurity engineers at NYU's Tandon School of Engineering discovered two areas of 3D printing that could be compromised by a malicious party - printing orientation and insertion of fine defects.

"These are possible foci for attacks that could have a devastating impact on users of the end product, and economic impact in the form of recalls and lawsuits," Nikhil Gupta, materials researcher and an associate professor of mechanical engineering at NYU, said in a press release.

When a product is built using a 3D printer, a computer assisted design (CAD) file is first sent by the designer. After the manufacturing software breaks the design up into manageable pieces and orients the printer head, it then starts to apply the material in ultra-thin layers.

However, the inputted CAD file does not communicate any specific instructions to the printer head regarding orientation, giving a criminal a loophole to alter the process without you knowing.

During the printing process, the orientation of a product can adjust its strength by as much as 25%, researchers said.

"Minus a clear directive from the design team, the best orientation for the printer is one that minimizes the use of material and maximises the number of parts you can print in one operation," Gupta said.

Given the rapid development and adoption of internet-based technology, particularly in the industrial sector and global supply chain, a cybercriminal may also covertly slip in 'fine defects' to modify a product while it is being printed that could go unnoticed in quality control inspections. These minute flaws, paired with environmental conditions such as light, heat and humidity, could weaken the defective product's integrity over time and eventually cause it to give way - a major risk for 3D printed industrial products such as spare parts for vehicles, airplanes, buildings and more that could have catastrophic consequences.

"New cybersecurity methods and tools are required to protect critical parts from such compromise," said cybersecurity researcher Ramesh Karri. "With the growth of cloud-based and decentralised production environments, it is critical that all entities within the additive manufacturing supply chain be aware of the unique challenges presented to avoid significant risk to the reliability of the product."

When the researchers inserted sub-millimetre defects between the printed layers of a product being printed as a test, they found that the introduced flaws could not be detected using post-production monitoring techniques commonly utilised by manufacturers such as ultrasonic imaging.

"With 3D printed components, such as metallic moulds made for injection moulding used in high temperature and pressure conditions, such defects may eventually cause failure," Gupta said.

Besides the manufacturing security risks, 3D printing technology could also be compromised to steal valuable intellectual property and print objects that could be used in other cybersecurity exploits.

In 2014, an anonymous cybercriminal claimed he could mass produce the spare parts needed to build ATM skimmers and fake point-of-sales (POS) terminals using 3D printing technology. In April, a group of Australian lock-pickers found they could 3D print keys found on patent sites to access restricted locks, demonstrating the exploit at the BSides Canberra security conference.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.