Labour needs a lot more than popular policies to win the election

Labour's manifesto has a lot the public will like - but the party lacks an overall vision for the country.

One certainty in politics is that, if you fail to define yourself, your opponents will do it for you and Labour's approach to politics over the last seven years is a good example of this in action.

Like the centre-left across much of the West, progressive parties find themselves caught between two groups with differing outlooks on the world. Stuck between their traditional base of blue-collar socially conservative voters and their new liberal recruits in the cities, the fear of alienating either one has led to an intellectual inertia that is costly at the ballot box.

You only need look at Labour's approach to Brexit to see this in action. Just one in five Brits feel Labour have a clear position on Brexit and in this vacuum the other parties have been able to make hay.

The Lib Dems can paint Labour as pro-Brexit, May's lapdogs waving our exit through whilst the Tories and Ukip can paint Labour as Brexit obstructionists who will do all they can to frustrate the process. Rather than pick a side, which could alienate one of Labour's two competing voters, the party has prevaricated and let others define its position.

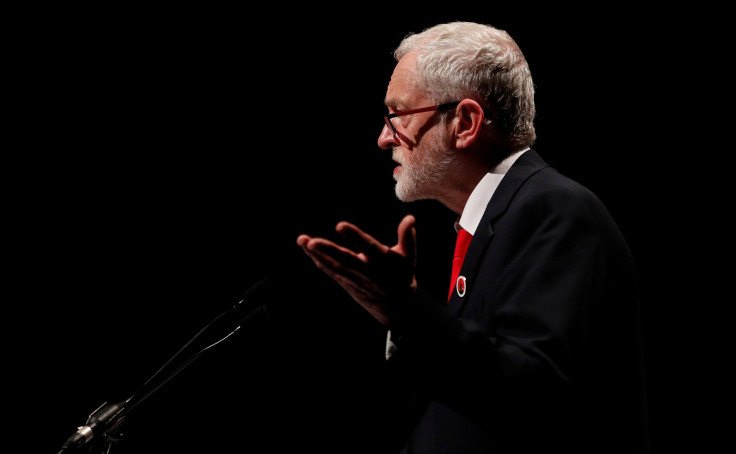

This discordant position is not restricted to Europe; on immigration, welfare, defence, and many others, Labour has abandoned the hard thinking needed and stuck with the simple. In lieu of having to decide on a vision of what Britain looks like under them, with the risks of alienating their supporters this entails, both Ed Miliband and Jeremy Corbyn have taken the easier option and focused on popular policies.

David Axelrod, Ed Miliband's advisor, coined Labour's 2015 election slogan as "Vote Labour and win a microwave" and it's unclear how Corbyn's Labour have done anything differently.

Renationalisation, health spending, more houses, police and better schools are all popular, of course they are, and they give Labour a positive message to go to the ballot box with. What they all lack, however, is a central vision which underpins them and so it is left to the Conservative party to define Labour, a job they are only too eager to take up.

For the many not the few is a start but it's still just a soundbite, there is no vision about exactly who this many and few are. The Conservatives can simply claim that the many are right-wing bogeymen (immigrants, benefits cheats etc.) and the few are people just like you. Throw in a raft of costly policies and, despite popular support, the British public is left asking how much all this will cost and believing that they will end up paying for it.

Under Miliband, or Red Ed as he was coined, Labour was easily defined by the Tories and the press as a high tax, high spend, anti-business party and Labour under Corbyn has done little to alter this perception. Proposing spending lots of money on nice things will do nothing to reverse this belief and only serves to further entrench it in people's minds as they worry about who will pay for it all.

There is no time before June for Labour to reimagine itself but, whatever comes after the likely defeat in a few weeks, Labour can no longer lazily hope that policies will make up for a lack of vision.

Whoever the leader is this summer, the first step is to decide what the Labour party is, who it stands for and what the country looks like under it. Once this has been done, policies should follow, not the other way around.

Be bold and ambitious because, without doing the hard lifting now, Labour's slide into irrelevance will show no signs of reversing.

Laurence Janta-Lipinski is a former pollster with YouGov and is now a freelance communications and political strategy consultant. He tweets at @jantalipinski.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.