Maduro's hollow victory: The end of democracy in Venezuela or the start of a revolution?

Venezuela's new constituent assembly allows President Maduro to silence his enemies. But the opposition won't just go away.

Venezuela's ruling Socialist Party and its allies won all 545 seats in the new constitutional assembly, but the result doesn't mean the country has fallen back in love with President Nicolas Maduro. It's simply a reflection of the fact that the opposition parties weren't standing in the election.

Polls showed that some 70 percent of Venezuelans opposed the vote, and many abstained from voting. Caracas was largely shut down, streets were deserted and polling stations were mostly empty, dealing a blow to the legitimacy of the vote.

However, Venezuela's National Electoral Council claimed that more than eight million voters went to the polls. This count was met with mockery and anger from members of the opposition, who said they believed only two to three million people voted. Independent analysis put the figure at around 3.6 million.

"The people have delivered the constitutional assembly," Maduro said on national television. "More than eight million in the middle of threats ... it's when imperialism challenges us that we prove ourselves worthy of the blood of the liberators that runs through the veins of men, women, children and young people."

Maduro is losing support even in former Socialist strongholds in rural areas and working-class inner-city neighbourhoods. The country's roughly 2.8 million state employees were ordered to vote for the constituent assembly, with many telling Reuters they were threatened with dismissal if they went against Maduro.

Ahead of the vote, the opposition organised a series of work stoppages as well as a protest vote against the constitutional assembly on 16 July that it said drew more than 7.5 million votes. "It's very clear to us that the government has suffered a defeat today," said Julio Borges, president of the opposition-controlled but largely powerless National Assembly. "This vote brings us closer to the government leaving power."

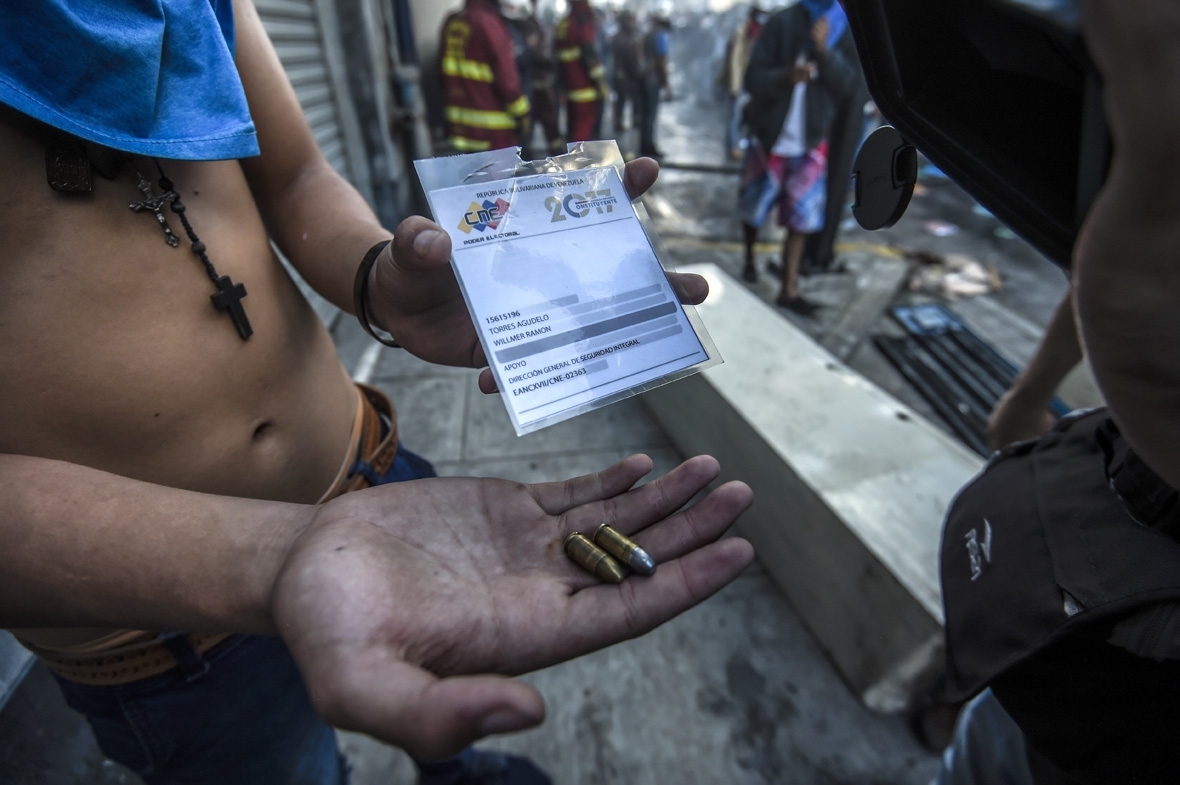

At least ten people were killed in violent protests as Venezuela went to the polls on Sunday (30 July), making it one of the deadliest days since massive protests started in early April. A bomb went off as a group of police officers on motorbikes sped past Caracas' Altamira Plaza, an opposition stronghold. The state prosecutor's office said seven officers were wounded.

Clashes were also reported in the volatile Andean state of Tachira, whose capital is San Cristobal, where witnesses told Reuters an unidentified group of men had showed up at two separate street protests and shot at demonstrators.

Fatalities over the weekend included two teenagers and a candidate to the assembly killed during a robbery in the jungle state of Bolivar. The state's Socialist Party governor, Francisco Rangel, said the death was a "political hit job" and blamed it on the opposition.

Opposition leader Henrique Capriles urged Venezuelans to protest again on Monday (31 July). "As of tomorrow, a new stage of the struggle begins," he said.

His critics say the election was a blatant power grab meant to keep Maduro in office despite his handling of the country's brutal economic crisis. Nearly two decades of heavy currency and price controls have asphyxiated business. Thanks to plunging oil prices and widespread corruption and mismanagement, Venezuelans have seen their purchasing power shredded by the world's highest inflation rate.

Millions of Venezuelans now struggle to eat three times a day due to shortages of products as basic as rice and flour. Falling ill can turn into a death sentence due to lack of medicines and deteriorating hospitals. With triple digit inflation, and a currency that has fallen 99 percent against the dollar since Maduro was elected in 2013, it's no wonder ordinary Venezuelans are growing increasingly angry at Maduro's handling of the crisis.

The UN refugee agency said applications for asylum lodged by Venezuelan nationals have "soared", with 52,000 already this year against 27,000 in all of 2016. This represents "only a fraction" of those in need of safe harbour from violence and food shortages, it said. Venezuelans have sought asylum mainly in the United States, Brazil, Argentina, Spain, Uruguay, and Mexico, UNHCR spokesman William Spindler said.

The new constitutional assembly will endow Maduro and his party with virtually unlimited powers. He has vowed to use the assembly to jail key opposition leaders, remove the nation's outspoken chief prosecutor from her post and strip opposition legislators of their constitutional immunity. Many in the opposition fear it will mark the end of democracy in Venezuela.

Maduro made clear in a televised address that he intends to use the assembly not just to rewrite the country's charter but to govern without limitation. Describing the vote as "the election of a power that's above and beyond every other," Maduro said he wants the assembly to strip opposition politicians of immunity from prosecution — one of the few remaining checks on ruling party power.

Declaring the opposition "already has its prison cell waiting," Maduro added: "All the criminals will go to prison for the crimes they've committed."

Maduro dismisses criticism of the assembly as right-wing propaganda aimed at sabotaging the brand of socialism created by his mentor and predecessor, the late Hugo Chavez. "The 'emperor' Donald Trump wanted to halt the Venezuelan people's right to vote," said Maduro as he voted. "A new era of combat will begin. We're going all out with this constituent assembly," he said.

Several nations including Argentina, Canada, Colombia, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Spain, Britain and the United States said they would not recognise the election. Maduro said he had received congratulations from the governments of Cuba, Bolivia and Nicaragua, among others.

Maduro has characterised the constituent assembly as a solution for Venezuela's long list of political and economic woes, and a concrete way of silencing his most vocal foes. But the opposition won't just go away. A prolonged conflict appears increasingly likely. Freddy Guevara, the legislature's first vice president and one of the highest-profile organisers of protests against the government, told Venezuelans to prepare for difficult days ahead. "After Sunday, it will not be easy for us," he said.

Benigno Alarcon, director of the Center of for Political Students at Andres Bello Catholic University in Caracas, said: "We're talking about a conflict that will last until there are elections."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.