Rhinconichthys: Evidence of extinct bony fish with huge mouth discovered in Japan and US

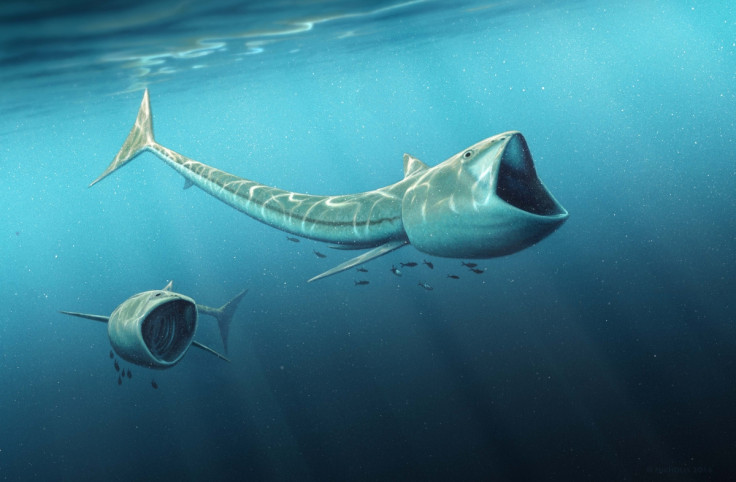

Scientists have found two new extinct fossil fish species in Japan and Colorado. Both species are characterised by their huge mouths, which open so widely so that they could gather as much plankton as possible when feeding.

The discovery, published in the journal Cretaceous Research, describes the US species – Rhinconichthys purgatoirensis – and the Japanese species – Rhinconichthys uyenoi. The fish have joined just one other fossilised species in the Rhinconichthys genus, discovered in England six years ago.

The researchers, from DePaul University, say that these species lived about 92 million years ago, a time when dinosaurs were still alive. The US species, R. purgatoirensis, was believed to be around 2-2.7m long, with the Japanese R. uyenoi slightly larger at 3.4-4.5m.

"Based on our new study, we now have three different species of Rhinconichthys from three separate regions of the globe," said Kenshu Shimada, researcher on the study. "This tells just how little we still know about the biodiversity of organisms through the Earth's history. It's really mindboggling."

The species discovered in the US was found by Bruce A Schumacher, as he was conducting field research in 2012. He noticed a potential fossil protruding from a rock in Colorado, and began to slowly chisel away at the surrounding material to reveal the fin rays of a bony fish. His discovery is the most complete Rhinconichthys yet.

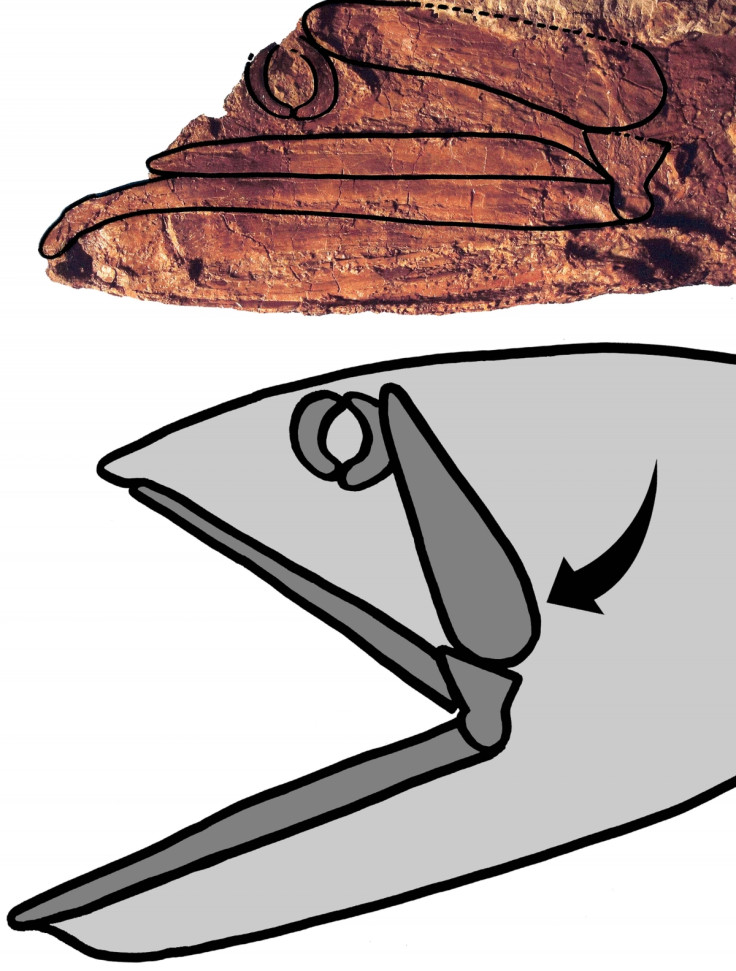

The most defining aspect to the Rhinconichthys genus is its peculiar mouth. Similar to a modern-day pelican, the fish had a huge mouth that could open extremely wide.

This is because one of its bones – the hyomandibulae – could extend like an oar-shaped lever to swing the jaws open to a wide angle, enabling it to draw in as much plankton as possible when swimming.

"The hyomandibula acts as an elongate lever," said Shimada, "allowing greatly amplified protrusion of the jaws and expansion of the buccal cavity.

"This specialised cranial construction was previously unknown among cretaceous bony fish, and functionally parallels that of the modern paddlefish Polyodon and many sharks."

The researchers write in the report that discoveries like this are changing historical interpretations of fish that feed on plankton.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.