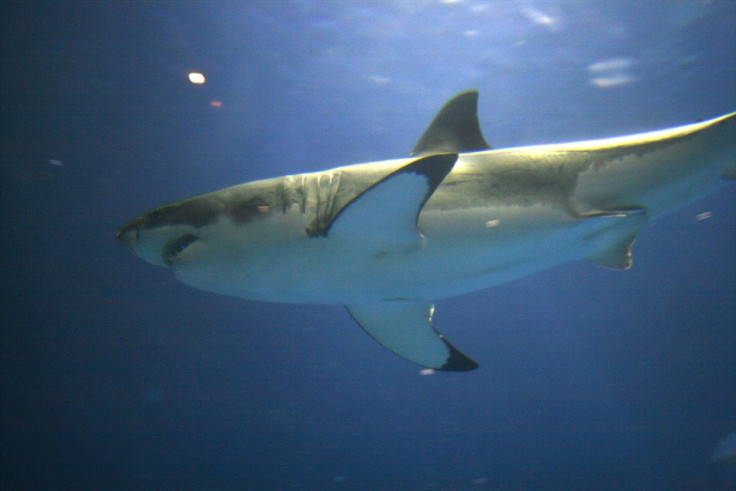

Surfer killed by great white shark in ocean off New South Wales

Fears of shark attacks led to beaches near Sydney, Australia, closing for nine days in January

A surfer was killed by a great white shark, in the oceans off Australia.

Tadashi Nakahara, 41, was less than 10m from the beach at Ballina, a seaside resort in New South Wales. He died from his injuries.

Nakahara is the second person known to be attacked by a shark in Australia this year, and is the first fatality.

Last month beaches near Sydney were closed for a record nine consecutive days by police, following a spate of shark sightings.

In an interview with the Times, Daniel Bucher, a marine ecologist at Australia's Southern Cross University, said attacks on surfers and swimmers by sharks were generally to find out whether they are edible.

"They are trying to find out what we are; we are sitting on the surface of the ocean and they are scavengers as well as predators and they like an easy meal," he said.

Sharee Pearson organises surfing competitions near Sydney. "They are definitely coming closer to shore," she said. "Surfing is getting bigger and bigger, and the sharks just seem to be getting closer and closer."

Scientists confirm that sharks are coming closer to beaches. That's partly because of increases in their natural food supply. The great whites – responsible for most fatalities around Australia – eat seals and whales. The numbers of those creatures are on the rise due to conservation policies, according to Daryl McPhee, a shark researcher at Bond University.

And the number of visitors to Australia's beaches is rising. A big factor is the large numbers of retired people going to the beach during early winter. That's when whale migrations are in full flow and sharks come after the whales.

Moreover, the deterrent effect of a fatality does not endure so that people stop exercising caution very quickly. "Usually, after about two weeks, the public goes back to normal," says Christopher Neff, a lecturer in public policy at Sydney University.

Despite the shark's fearsome reputation, shark attacks are extremely rare.

Researchers at the University of Flordia recorded 72 sharks attacks during 2014 worldwide – which is about average – of which only three were fatal. Two of the fatal attacks occurred in Australian waters.

George Burgess, curator of world shark attack data at the University of Florida's Museum of Natural History, said that beachgoers are more likely to win the lottery than encounter a shark.

"It's amazing, given the billions of hours humans spend in the water, how uncommon attacks are," he said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.