Ten 'crude' years: Manoeuvres, wheeling and dealings at Opec over a volatile decade for oil markets

Having spent the last 10 years covering Opec, the IBTimes Business Editor provides a peek inside the 'central bank of oil'.

The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries has been inseparable from the global energy market since the year of its founding in 1960, when Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela, came together to form an "intergovernmental body" to protect the interests of crude oil producers and their state-owned companies; and to counter dominant Western oil companies or the so-called "Seven Sisters."

The sisters included Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (now BP), Gulf Oil (now absorbed by Chevron), Royal Dutch Shell, Standard Oil Company of California (now Chevron), Standard Oil Company of New Jersey (later known as Esso and then Exxon), Standard Oil Company of New York (Socony, later known as Mobil, now part of ExxonMobil) and finally Texaco (later merged into Chevron) who controlled much of the crude market.

Over the decades since, Opec has grown to be 'a' dominant, if not 'the' dominant force in global oil markets. Its members – currently numbering 14 countries – account for nearly three-fourths of the world's 'proven' oil reserves, with 'Big Oil' – the phrase coined to represent powerful oil companies – forced to be a part player.

In 2007, while working for a Canadian research firm, your correspondent, then a relative newbie to oil markets, was dispatched to Vienna, Austria, where Opec had been headquartered since 1965, to cover and analyse the goings-on as the oil price was fast approaching $100 and 'peak oil' theories about the planet running out of the crude stuff were all the rage.

And what a ride it has been ever since, following the ups and downs, highs and lows of Opec in relation to the wider market, and making the near biannual 'crude' pilgrimage to the capital of Austria for over 10 years and counting. Below are some reflections, episodes and experiences from that journey.

World's 'central bank of oil' and not a cartel?

Around the turn of the millennium, a subtle shift happened in the global crude market. The burgeoning economies of China and India – currently world's leading and third-largest importers of crude oil respectively – needed more of the crude stuff, and cargoes started being diverted east. Opec's clout, traditionally strong in Western capitals, spread to oil dependent emerging economies.

Given its share of global production averages above or around 40%, many analysts call Opec a cartel as the body acts in concert to protect its interests, sets a collective production quota and often alters production to support the oil price.

In 2010, I put it to then Opec Secretary General Abdalla Salem El-Badri whether it was indeed a cartel? "That is an unfair description. Opec does not cause volatility in the oil market or support price one way or another. Speculators do that. We are a force for market stabilisation that protects its members' interests, and invests to further cooperation in the market."

Yet, whatever it does invariably impacts the crude price. Perhaps then, it would be fair to describe it as the World's 'central bank of oil'. Full disclosure – the phrase was not coined by me – rather by economist Jason Schenker, boss of Austin, Texas, US-based Prestige Economics.

"There are many sources of oil around the world, and various permutations affect the crude price. Beyond Opec, there are several producers, including US shale players, whose volumes matter. But I would call them 'buffer' producers, because in a classic sense the world's only swing producer is Saudi Arabia, and its production level accounts for a third of Opec's headline production," Schenker explains.

That headline production has fluctuated between 28 to 33 million barrels per day (bpd) over the last decade, especially as Opec members' divergent economic needs often lead to individual quotas being flouted. With no policing mechanism in place, that's quite 'un-cartel' like.

"Yet, Opec's spare capacity – i.e. the volume of oil production that can be brought on within 30 days and sustained for at least 90 days – generally underpins the global oil market's ability to respond to potential crises that threaten to dent supplies. Hence, it remains the central bank of oil for me," Schenker concludes.

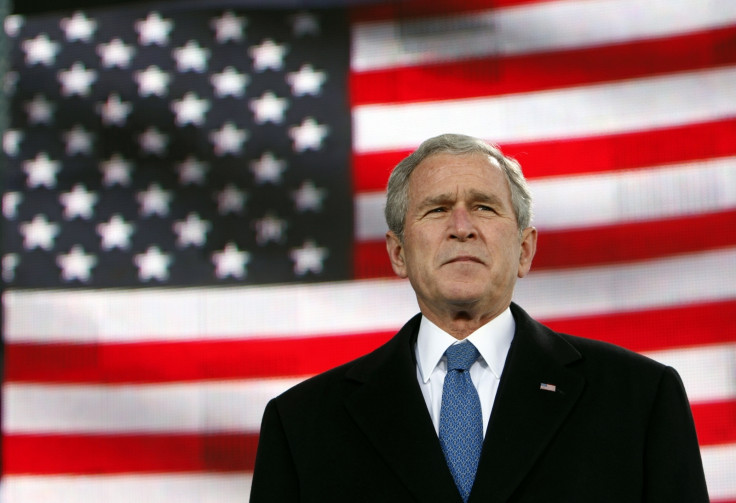

Calls from George W. Bush to tussle with shale players

With geopolitics and oil markets intertwined, Opec has been through several crises documented over the last five decades – the 1973-74 Arab Oil embargo, 1979-80 oil price slump, both Gulf Wars, the (ongoing) Libyan civil war, and constant Saudi-Iranian jostling for power. I have had a front row seat to two such crises.

Over the fourth quarter of 2007, the global financial crash was merely a nascent US housing market crisis, and a growing global economy was nudging the oil price toward $100 per barrel. The US shale revolution was not fully among us and Washington was still fretting about energy security, when I first turned up to cover Opec.

It had become commonplace for then US president George W. Bush to call on Opec to raise production to help lower the price. But within Opec, the hawks, like Iran and Venezuela - no friends of President Bush - would brief us scribes that they'd like a production cut to perk up the price further, while the doves, led by Saudi Arabia, sympathetic to the American cause of wanting to lower oil prices, would call for a no change scenario.

In September 2008, with the oil price threatening to touch $150 at one point, according to some analysts' expectations, things came to a head when the then Saudi oil minister Ali Al-Naimi stormed out of a negotiating session after rival members voted to cut Opec output in a bid to raise the price further, coming up with some very un-ministerial terms to describe his Iranian counterpart.

Subsequent, anonymous briefings suggested Opec's biggest contributor would remarkably not observe its own quota. Over the next few months, the oil price slid below $40 as the financial crash hit the global economy, and did not return to $100 until the Libyan Civil war in 2011.

Fast forward to June 2014, with Islamic State (ISIS) advancing into northern Iraq, the oil price was sitting pretty at $115 per barrel. Having met barely 24 hours before the news of the ISIS advance broke, Opec had decided to maintain its 'official' production level at 30 million bpd, though the unofficial level was well above that and plenty of barrels were in play.

Physical crude analysts were left scratching their heads as to why the oil price was so high when US, Russian and Saudi oil production was at record highs, and demand growth was nowhere near what the market had seen 2012-13. Of the big five importers US, China, India, Japan and South Korea, only the Indians were buying more.

And then, unsurprisingly it happened. In July 2014 the oil price started declining gradually, despite the unfolding tragedy in Iraq, Russia-Ukraine tensions, Libya being up in flames and Nigeria in its state of perennial strife.

The so-called "risk premium" started evaporating in an oversupplied market simply because the world's largest crude importer, the US, wasn't turning to the global market quite so much, courtesy of its own production uptick thanks to shale exploration.

In fact, US production had risen to a historic high of 8.44m bpd in the summer of 2014. Opec knew a serious medium-term competitor was emerging and something had to be done. The answer came at the next Opec meeting from power broker Al-Naimi.

Leave it to Ali

For over two decades, and encompassing most of the time I've covered Opec, every word Al-Naimi uttered was lapped up by the oil market. It wouldn't be otherwise, if you were the oil minister, as he once was, of Opec heavyweight Saudi Arabia between August 1995 and May 2016.

At every Opec meeting, it's the Saudi envoy whom every journalist rushed to and wouldn't get a morsel of a soundbite if the man himself was in no mood to provide it. His signature move prior to each meeting was a dawn power jog, later a power walk, around Vienna's Ringstrasse or Ring Road.

Not a chance to missed, half world's press also surrounded him when he took to the pavement with security guards, complete with kit and caboodle, providing a spectacle for bemused locals wondering what on earth was going on.

On one such outing, when I attempted to ask about the upcoming meeting, Al-Naimi deftly moved the conversation to subject of the prolonged nature of Indian weddings and your correspondent's bachelorhood. When Javier Blas, once of the Financial Times and now of Bloomberg, asked about how balanced the market was, Al-Naimi quipped: "The market balances itself out, I don't balance it."

Yet indoors at Opec, firm as he was, Al-Naimi made sure they heard him and so did the global market. His response to shale, much to the chagrin of fiscally desperate economies of Iran and Venezuela, was to use the market phrase 'keep the taps' open. The Saudi veteran's logic was simple – let the market take its own course, and let the lower oil price in an oversupplied market dictate the survival of the fittest.

Only problem was that shale players proved themselves adept at surviving too, especially those with viable exploration acreage. A whole lot of pain followed for the oil industry - billions of investment dollars were put on ice, thousands in the industry lost their jobs, US saw hundreds of small oil explorations firms go bust, and yet the additional oil barrels kept coming on to the market.

The Russians are coming, the Russians are coming!

Given his historical distrust of non-Opec Russia, another major oil producer, Al-Naimi saw little point in talking to the Kremlin, given past failures to get them to cooperate as he later detailed vividly in his autobiography.

Not only that: the Saudis and several others raised their production levels in a bid to flood the market and price out the competition. US shale explorers, driven by the spirit of private enterprise, kept plugging away too, raising US production from 8.44 million bpd to 9.6 million bpd; a level tipped to touch 10 million bpd in 2018.

The sheikhdoms were hurting as well, having had to dip into their massive foreign reserves to sustain their social programmes in the face of declining proceeds of oil sales. Yet Al-Naimi did not relent and Saudi production actually rose above 10.5m bpd. This was more than 1 million bpd above the Kingdom's 2014 levels.

But by the summer of 2016 the new Saudi ruler, King Salman, sent Al-Naimi packing into retirement and replaced him as oil minister with Khalid Al-Falih, former boss of state-owned oil company Aramco.

Opec blinked at its next meeting, shale market froth disappeared and the end result was a scored draw in the Sheikhs verus Shale tussle. At the end of it all, replacement of the colourful Al-Naimi by the more businessman-like and policy wonk-ish Al-Falih was something few saw coming so suddenly.

Meanwhile, Al-Falih got talking to the Russians and by the end of 2016, Opec led by Saudi Arabia, and a select group of non-Opec producers led by Russia, inked a joint production cut of 1.8 million bpd, which was subsequently rolled over in May 2017 stabilising Brent futures in the $55-$65 range.

There's something about El-badri

There are plenty of power-plays in the corridors of Opec. Take the powerful Gulf producers block led by Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates. Then there are the aforementioned hawks who almost always want a higher oil price given the state of their economies, and their opponents the doves, i.e. mostly rich producers who believe cutting oil production and too high a price might drive the world to seek alternatives.

There is a near permanent undercurrent to it all provided by persistent and historic Saudi-Iranian tensions. Managing all the shenanigans and putting a brave public face falls to the Opec Secretary General, a politically sensitive appointment, as the current occupant of the chair Mohammed Sanusi Barkindo of Nigeria would testify.

However, before Barkindo became the compromise candidate for the post, dissensions within Opec meant it could not agree on a candidate for a number of years to succeed El-Badri, who was first appointed on 1 January 2007, and kept getting his term extended over Opec meetings all the way up to 31 July 2016, making him the longest serving Secretary General ever.

Analysts called him the "Switzerland" of Opec. In more ways than one, El-Badri was a real trooper who kept getting reappointed, as each Iranian backed candidate would be voted down by the Saudis and vice versa.

At one post-summit briefing in 2013, El-Badri was even given an ironic round of applause by journalists to bid him farewell, full well in the knowledge that yet again Opec had failed to name a successor. However, he maintained his sense of humour and went through the entire press conference never once losing his composure.

Perhaps in appointing him back in 2007, Opec raised the bar very high. Prior to his arrival at Opec, the University of Florida educated El-Badri served as Libya's minister for oil and electricity. This was followed by several ministerial stints including one as deputy prime minister from 2002 to 2004.

After assuming the Secretary General's position, El-Badri handled some real challenges and a term that began with oil price first spiking above $140 and then dipping below $40, followed by the worst financial crisis in modern history.

To give the last word to the man himself who once said: "My [repeated] reappointment as Secretary General was down to the wisdom of ministers and I have no further comment to make."

In turn, he kept the peace at the Opec table of wise men and women.

Whether "Dow Jones or Tom Jones, no media ID, no access"

Events such as Opec summits usually require careful press management, given security implications and half the world's press wanting in. For ten years and counting, the first face I almost always see at Opec is senior press attaché Mahid Al-Saigh.

I vividly remember on my very first attempt at getting an Opec accreditation some ten years ago and walking into the venue to find an agitated Al-Saigh telling a journalist without an identity card or a passport: "Whether its Dow Jones or Tom Jones, we need to verify your ID and passport. You have turned up with neither. This is Opec, not an amusement park, no ID, no access!"

And meeting after meeting, the diligent Al-Saigh and his team carry out the drill, doubtless losing their beaming smiles to remind the odd errant scribe that he/she are not asking to enter a park but a secure building that will host some of the most important oil ministers in the world.

"The Opec press office is here for your service, but we have to keep order. Protocols are established for a reason given the nature of the world we live in. We never digress from that," Al-Saigh says.

In 2009, lot of nostalgic tears were shed when Opec moved from its old headquarters (pictured below) on the banks of the Danube canal to Helferstorferstraße 17 (pictured at the top of this feature) next to the Vienna Stock Exchange.

It's here that every newsire, magazine, journal, newspaper and TV journalist imaginable currently arrives in town for the ministers' summit, and pre-announcement media scrums, dubbed, rather unceremoniously for some as the "gang bang."

Amid the commotion, Opec's internal broadcasts are coordinated by a well drilled machine anchored by broadcaster Eithne Treanor, herself a regular fixture on the energy speaking circuit.

It falls on Treanor and the Opec broadcasting team to drive the live video stream from the venue. That includes covering both press conferences, opening briefings, producing an insight programme, interviewing ministers and last but not the least, analysts such as myself.

"We have to be on our toes, like any other broadcasting outlet. While there is a set schedule, there are always impromptu interviews to keep the live feed going. The buzz is amazing and its a privilege to have this assignment, and work with the dedicated Opec broadcasting crew," Treanor says.

And the background din to the broadcasts that Treanor coordinates is provided by journalists and analysts from no less than 90 countries spreading Japan to Canada, India to South Africa and all else in between, crammed into the media briefing room (pictured above).

In fact, time flies so fast that the same motley crew of writers and analysts, are now deliberating "peak demand" for oil, instead of "peak oil" with electric vehicles providing the talking points. But Opec should not have too much to worry about on the demand front, if the International Energy Agency (IEA) is to be believed.

In 2016, we had 2 million electric cars in the world, that's less than 1% of total global car sales, the IEA recently noted. Furthermore, Dr Fatih Birol, the agency's Executive Director, opines that even if one in every two cars is electrical, global oil demand growth will keep pace.

"That's because the primary demand drivers of oil consumption, contrary to popular perception, are not cars. Bulk of the demand comes from trucks, aviation and petrochemical manufacturers, so it is too simplistic to assume 'peak demand' for oil in a matter of years and tie it in to the growth of EVs."

Opec would certainly be hoping that is the case, so do all the scribes covering it! So here's to another 'crude' decade.

Gaurav Sharma is the Business Editor of IBTimes UK. He has been a financial journalist for over 15 years, with a core specialisation in macroeconomics and commodities. Follow Gaurav on Twitter.