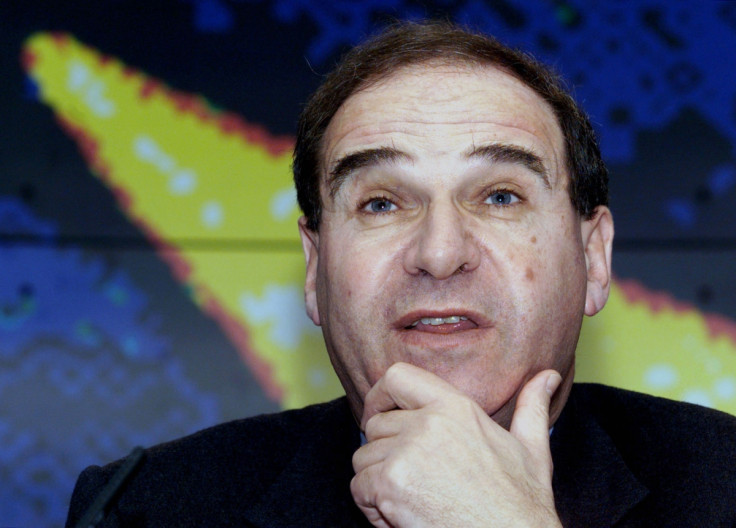

Tom Watson MP: Will hubris and the Westminster paedophile scandal ruin deputy Labour leader?

Tom Watson has a lot of friends. But he makes his friends by making enemies, often of powerful people. The bulky Labour Party deputy leader is a brawler, a bruiser and, according to some of his critics, a bully.

The West Bromwich East MP's full-frontal assault on Rupert Murdoch over the phone-hacking and bribery scandal that engulfed the media mogul's businesses in Britain earned him a battalion of new fans on the left. And his pursuit of the Westminster paedophile scandal, in which he became the standard bearer for a campaign to prove some of the most senior men in the British establishment were responsible for gruesome criminality against children, has brought him yet more admirers.

But Watson demonstrates one serious character flaw found in the doomed figures of ancient Greek mythology: hubris. As cracks form in what might have been the most explosive story in British political history, has Watson flown too close to the sun?

Watson, a digital enthusiast and gamer in his spare time, has a cyclical career. He gathers confidence as he builds his wings, before soaring too high and getting solar-singed, sending him falling back to earth where the wing-building starts again.

It was as a backroom brawler and loyal Brownite that he first earned his reputation for fighting in the dirt. Watson was a leading figure in the coup that brought down Tony Blair as prime minister, ushering in his boss, Gordon Brown, in 2007.

Facing down Watson after he resigned as a junior minister in 2006 to destabilise the prime minister's leadership, Blair called him "disloyal, discourteous and wrong". Watson still has a reputation among some on the right of the party as a dastardly plotter, someone not to be trusted – reputational scars from old fights. Writing in 2015, Blair's former political secretary, John McTernan, described Watson as a "factional warlord".

Watson was rewarded by Brown with another junior position in the government, the role of minister for digital engagement, before Labour lost the 2010 general election and he was consigned to the backbenches again.

And it was from here that he worked his way back up. Despite his past, Ed Miliband made Watson his election campaign chief, a nod to his ability as an effective political street fighter. But in 2013, Watson resigned amid the Falkirk selection scandal. He is closely linked to Unite – he once shared a flat with Len McCluskey, the union's chief – and supported its preferred candidate for Falkirk. Unite was accused of trying to "flood" the local party with members to get their person, Karie Murphy, selected. The union denied any wrongdoing, but Watson saw better to quit.

He became the bane of the Murdoch press when he dedicated much of his energy to weakening the octogenarian's empire. First by winning a vote on the Commons media select committee to brand Murdoch "not a fit person" to run a major business. And second by campaigning forcefully for tighter regulation of the press amid the Leveson Inquiry.

This culminated in a book by Watson and the journalist Martin Hickman, Dial M For Murdoch, which documents "a criminal conspiracy involving politicians, the police and the press". Watson said he was harassed by Fleet Street journalists, who probed his political and private life for stories to discredit him. He has made a powerful enemy in Rupert Murdoch.

With much of the phone-hacking saga now over, and the prospect of tight press regulation kicked into the long grass, Watson has turned his focus to a new and much darker scandal – allegations of an establishment paedophile ring and the sexual abuse of young children.

Several people have come forward, some through the investigative news website Exaro which is collaborating with Watson, to make a number of lurid allegations about senior past members of the British establishment who they say abused them when they were children in the 1970s and 1980s. And police officers have also claimed they were warned off investigations into such cases brought to their attention in the past.

One of those Watson says he has heard allegations against is the former home secretary, Leon Brittan. Watson led a campaign to have Brittan reinvestigated on an old allegation of raping a 19-year-old woman in 1967, for which he had already been exonerated. The police reopened their investigation, but once again said he had no case to answer. Brittan – who Watson said was "as close to evil as any human being could get" – died of terminal cancer before he knew police had absolved him of this allegation. Now Watson is under pressure to apologise to his family for the distress caused.

Separate claims made about the purported Westminster paedophile ring – which include Brittan among others – are also under pressure after a BBC Panorama documentary cast doubt on some of the testimony given to Exaro and Watson, suggesting it was faulty and may not survive scrutiny. Exaro stands by its reporting and said Panorama conducted a "smear of survivors".

But some are beginning to question whether Watson, who says he is merely pursuing the allegations made by those claiming to be victims of child abuse so they are taken seriously by police, has gone too far this time. There are reports of division among officers investigating the claims over their credibility. One of the most scurrilous accusations – that a girl was murdered by the paedophile ring at a notorious property in London's Dolphin Square, where their parties are said to have taken place – was found to be unsubstantiated by police. And the chief of one investigation reportedly quit the probe because of interference by Watson.

"When he hounded a dying man to his grave, Watson sank lower than the News Of The World reporters he and Hacked Off once fought," wrote the journalist Nick Cohen in the Observer. "However invasive and prurient their scoops, they were at least true. Unless convincing witnesses come forward, you will not be able to say the same about Watson's 'exposé'."

Watson points to the likes of Jimmy Savile and Cyril Smith MP – both posthumously outed as paedophiles – as evidence of high-profile celebrities and politicians involved in child abuse, whose actions have been covered up before.

"In October 2012, I asked a question in parliament about a network of paedophiles," wrote Watson in the Huffington Post, defending himself against critics over the Brittan affair. "An investigation into their activities had been closed down before reaching a conclusion. Two of them have now been convicted and they are serving long sentences. I have passed more information to the police since then and a third man has also been sent to prison partly as a result of this. My motivation throughout has been to help victims as best as I could."

Watson's reputation now hangs on the fate of the remaining inquiries into the Westminster paedophile allegations, which stretch from London to Jersey to Northern Ireland, and whether they are substantiated or scurrilous. Watson was elected convincingly as deputy leader of the Labour party, another step up the ladder of his political career and reward for his relentless campaign work.

Now he has even more at stake if he is wrong. His downfall would be welcomed by the many enemies he has made over the years. But if he is right, his campaign will be vindicated, justice will be served, and Watson's ascendancy will continue while his critics watch in silence.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.