Unexpected events can force governments to change course - so let's hope this one rethinks the cuts

The UK general election of 1992 was won by the Conservatives, to the surprise and embarrassment of most pollsters. The Tories had been in office continuously since 1979. But by ditching Margaret Thatcher in 1990, when it was generally considered that she had become an electoral liability, and selecting John Major as its leader, the party pulled off a coup. Among other things, it was helped in the spring 1992 election by the appeal to the electorate of its familiar theme that Labour was the "tax and spend" party, and could not be trusted with the economy.

However, within months, it lost its own reputation for economic competence when, on Black Wednesday, 16 September 1992, the pound was withdrawn in ignominy from the European exchange rate system, the precursor of the single currency.

Major had been the chancellor of the exchequer who finally wore down Thatcher in autumn 1990 and persuaded her to put the pound into the system when she was politically weak – so weak that she was forced by her most highly regarded Cabinet colleagues to resign shortly afterwards.

But not only did the Black Wednesday debacle erode the Tory reputation for economic competence, it so angered the eurosceptic wing of the party that from then on, a group of Major's colleagues in the Cabinet fought a guerilla war to undermine his authority.

In this they were urged on by Thatcher, who became known as "the back seat driver". Major was so angry about this constant process of attrition that in an unguarded – or, who knows, possibly guarded – moment, he referred to them as the "bastards".

The Black Wednesday episode haunted the government right up to the next election in 1997. In that election, there was also a delayed reaction to Thatcherism and a feeling that the health service, the education system and the transport infrastructure were so run down that perhaps it was time for some action by the state.

Under the duumvirate of Tony Blair, as prime minister, and Gordon Brown as chancellor, there was a two-year "freeze" on public spending – ostensibly to establish "economic credibility", although, in this observer's view, the surge in spending could have begun immediately (they had a majority of more 180, for goodness sake!).

At all events, from 1999 onwards there was a serious expenditure programme that did much to improve the condition of the public services. Then came the financial crisis of 2007-08 and the Great Recession.

The Conservatives won the general election of 2010 at least in part because the party successfully blamed the dramatic rise in public sector borrowing and debt in 2008-10 on "Labour's profligacy". But, as Sir Nicholas Macpherson, the permanent secretary to the Treasury, pointed out – exercising true civil service independence – it was not a public spending problem but "a banking crisis, pure and simple".

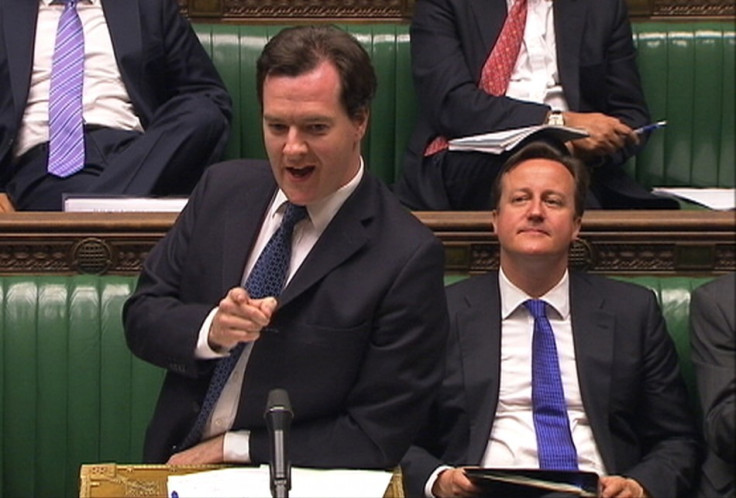

Nevertheless, Cameron and Osborne successfully sold the "public spending crisis" interpretation to the British public, and won two elections on a platform of "austerity", as in cuts, or reduced increases in public spending, including to essential public services, such as "flood protection".

This at a time when global warming appears to be increasing the frequency and intensity of flooding in Britain.

The scene shifts to the present day. Osborne has made a big thing about the need for a revival of industry in the north of England, what he calls the "Northern Powerhouse". But the more immediate concern is the opening of the Northern Floodgates. Even the Daily Mail is calling for extra public spending to address what is manifestly a serious crisis.

Until this month, the Conservative Party has been obsessed by the subject of Britain's place in Europe and the coming referendum. It has also been basking in complacency at the weakness of the Labour opposition under its new leader, Jeremy Corbyn.

It was a predecessor revered by Cameron, namely Harold Macmillan, who, when asked what he feared most, replied "the Opposition of events, dear boy". This was a dig at the putative weakness of the Labour opposition at the time, but principally an implied admission that unexpected events can force governments to change course.

Is it too much to hope that the public reaction to these floods will change attitudes towards "tax and spend"?

William Keegan is a journalist, academic, and the senior economics commentator at The Observer. He has published his latest work – Mr Osborne's Economic Experiment - Austerity 1945-51 and 2010 (published by Searching Finance).

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.