Why are there so many hurricanes these days? Irma, Harvey and more explained

Favourable conditions in the Atlantic are fuelling devastating tropical storms.

Hurricane Irma, one of the most powerful storms ever recorded in the Atlantic Ocean, is currently touching down on Cuba and Florida after leaving a trail of devastation in the Caribbean.

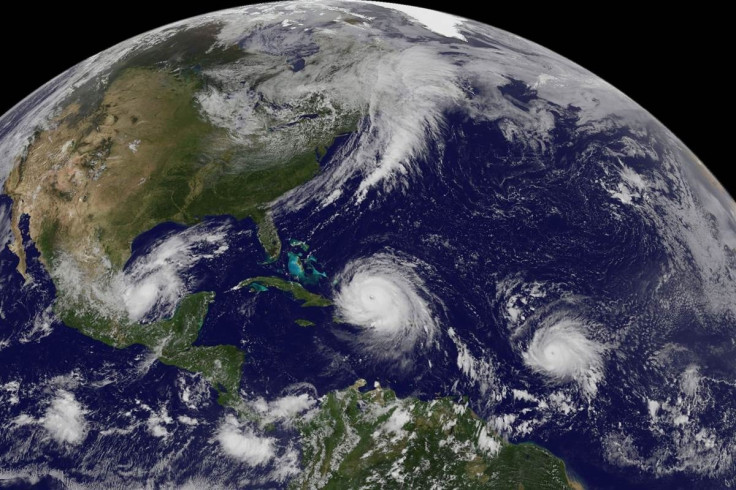

Coming just days after Hurricane Harvey wreaked havoc in Texas and Louisiana – killing at least 70 people – and with two more storms, Katia and Jose, raging nearby, it would be tempting to think something unusual was occurring – especially given the blanket media coverage.

But how out of the ordinary are recent events? And is climate change a factor?

Firstly, it is important to note that we are currently in the "peak of the hurricane season, so having hurricanes in this region is not unexpected", a Met Office spokesperson told IBTimes UK.

"The North Atlantic hurricane season runs from June-November, with peak activity during August-October. During peak season around 96% of all Atlantic major hurricanes – categories 3, 4 and 5 – occur", they said.

To put this in perspective, an average Atlantic storm season will produce around six hurricanes, with three of those becoming major hurricanes – meaning winds of 111 mph or more. And in total, an average season will produce 12 named storms. Storms are named if they reach wind speeds of 39 mph or more.

So far this season we have seen five Atlantic hurricanes, including two major ones in Irma and Harvey, and 11 storms overall. As we are only halfway through, there is certainly the potential for there to be an above-average number of storms this year.

However, in comparison to the 2005 hurricane season, which is considered the most active in recorded history, we are still a long way behind. That year saw a total of 15 hurricanes.

In short, while there may well be more hurricanes to come, it would not be totally out of character for this time of year.

Having said that, there are certain aspects of this season that do stand out.

One is that major storms have occurred outside their normal range in terms of both the time of year and geographic location. For example, Arlene was one of only two named tropical storms to occur in April and was the northernmost on record, while Irma was the easternmost category 5 hurricane to ever occur.

And while storms often form back-to-back, if Irma makes landfall in the US as a category 4 hurricane or above. it will mark the first time two storms of such strength have hit the country in the same season.

Irma itself is certainly exceptional in terms of both its high wind speeds – which reached 185 mph - and its longevity as a category 5 storm. While four others with higher wind speeds have been recorded in the wider Atlantic region, they all occurred in the Caribbean or Gulf of Mexico where conditions are more favourable for producing high wind speeds.

In 1980, Hurricane Allen reached a record speed of 190 mph but this top speed was sustained for only 18 hours in comparison to Irma's 37 hours.

So, are conditions particularly favourable to strong storms at the moment?

"All the characteristics required to produce an intense hurricane in the Atlantic are coinciding", the Met Office said.

"Firstly, sea surface temperatures under Irma are 1 to 1.5°C higher than the average for this time of year providing abundant moisture and warmth. Secondly, wind shear – the change in wind with height - is low meaning air can flow in up and out of the hurricane very efficiently, thus promoting intensification. Thirdly, there are no drying influences at present such as pockets of Saharan dust which sometimes drift out over the Atlantic."

Furthermore, Irma is moving fast enough to prevent cool water that is sucked-up into the hurricane from having any impact on the continued feed of warm, moist air.

But what about climate change? Is it affecting these storms?

"The most obvious link – especially for Harvey – is that warmer air holds more moisture - this is known as the Clausius-Clapeyron relationship", Chris Brierley, a senior lecturer in climate science at University College London told IBTimes UK.

"So, in a warmer world, there is more water in the atmosphere to rain out. The extreme precipitation of Harvey would probably not have been a US record without climate change. Warmer upper oceans – it isn't just the surface – prevent any cold water being brought to the surface and holding back the storm", he said.

However, it's important to stress that the impact of climate change – specifically global warming caused by the burning of fossil fuels – on the formation of storms is the subject of much ongoing debate.

"Whilst research using climate models suggests that high intensity tropical cyclones are likely to become more frequent in the future we cannot definitively attribute a single event, or recent series of events, to climate change at this time," the Met Office spokesperson said.

"This is due to the large natural variability in tropical cyclone activity regionally, and from year to year, and issues relating to the changes in observing techniques over the last few decades. The latest research suggests that there may be an increase in tropical cyclone intensity in the future, under continued global warming. However, the models also indicate that tropical cyclone frequency could either remain unchanged or even decrease," they added.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.