African migrants heading for Europe die of hunger and thirst in Sahara desert [Photo report]

At least as many migrants may be dying of hunger and thirst in the Sahara as are drowning in the Mediterranean.

The number of people attempting to cross the vast desert to reach Libya and then Europe could more than double this year to 100,000, according to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM).

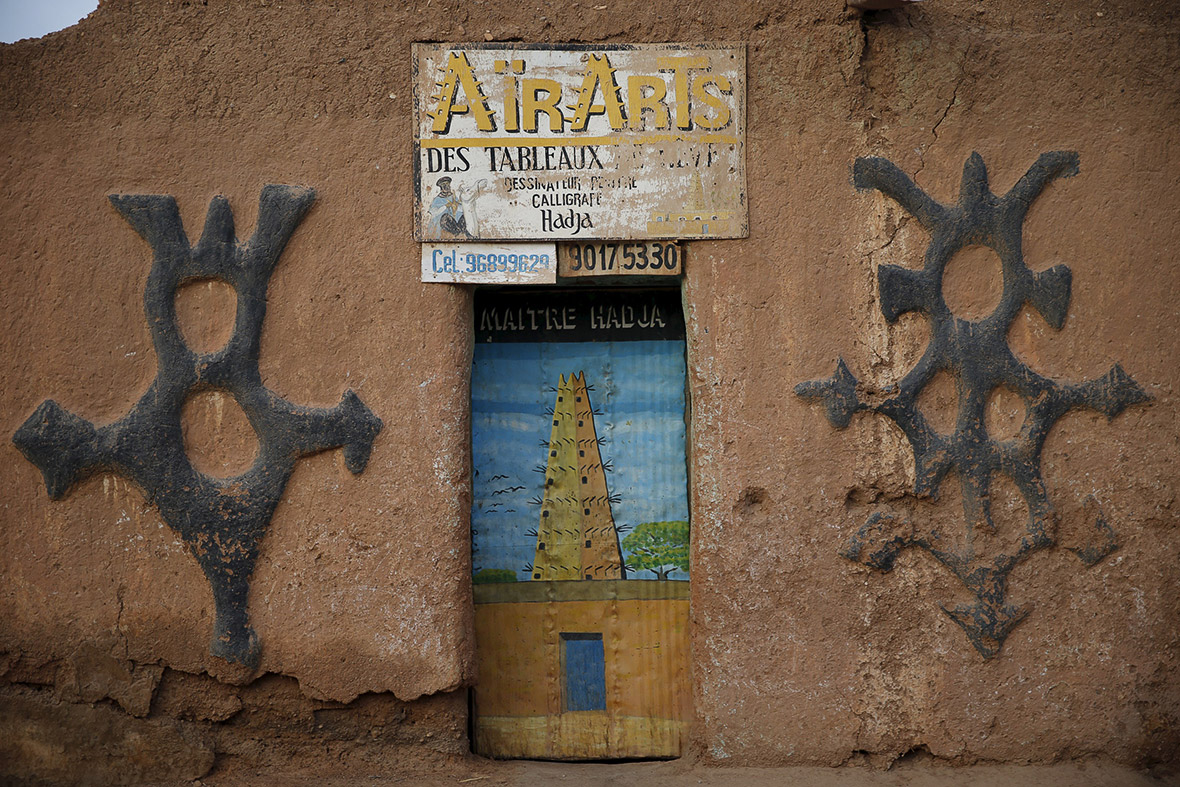

The town of Agadez in Niger is one of the main transit points in the Sahara for migrants leaving impoverished West African nations in search of a better life.

Migrants, some of them just teenagers, scramble onto the back of a truck in Agadez, jostling for a place on the journey north across 1,200km of dunes to Sabha in southern Libya – a route plagued by bandits and scorched by the relentless desert sun.

Nineteen men pack into the truck for the three-day trip, each clutching a yellow plastic jerry can of water swathed in cloth. Those on the edge sit astride a long wooden stick, to prevent them falling off during the night time journey across the Sahara.

"The crossing is very difficult. I know that I have launched myself into a dangerous adventure. It's a bit frightening, but I'm going to try to deal with it because in life you have to be brave. I will keep my spirits up along the route so that at the end of the day I can collect the reward," said Ismael Fousseni, a 16-year-old who quit school in Benin to travel with his brother and another friend.

He was spurred on by fellow migrants who've sent messages via social media of their success in reaching Europe. "With social networks, WhatsApp, Viber, we can communicate with our friends who are in Europe. They send us photos of their new adoptive parents there, and all of this gives us the appetite to get there and search for more money," said Ismael.

As night falls, the pickup truck rolls out of the metal gates of the departure compound and snakes through the sandy back streets of Agadez, passing groups of Muslim men kneeling in evening prayer. It drives unhindered past a police checkpoint on the outskirts of town and into the blackness of the desert.

The risks are high. Mohamed, a driver, said he was attacked last week by Touareg bandits wielding AK-47 assault rifles who opened fire on his pickup when he refused to stop, wounding a migrant in the leg.

A new tough law against people smuggling, approved under pressure from European Union donors, includes sentences of up to 30 years in prison for those profiting from migrants. However, the migrants continue to flood in, many of them passing through smugglers' compounds known as 'ghettos'.

A 2013 police report seen by Reuters identified at least 70 ghettos in Agadez, many of them segregated by nationality for travellers from Nigeria, Senegal, Ghana, or Mali, and operating with the complicity of local security forces.

Many of the ghettos in Agadez line the dirty back streets, in squat houses behind red mud walls with no windows, just metal gates that occasionally offer glimpses of young men inside.

Smuggling has long been a way of life in Agadez, an ancient caravan town. The streets are full of cars stolen from Libya, whose borders are largely unsecured, and locals speak in hushed tones of drug convoys that traverse the desert.

With the collapse of foreign tourism due to the rise of armed Islamist groups in the Sahara, smugglers say there is nothing much else they can do to earn money.

David Ousseni is a 34-year-old middle-man. He runs one of the many ghettos in Agadez – just a place, he says, where migrants can have the opportunity to rest before they leave. "As soon as we have a full cargo of people, we call a driver and he comes. They load them up and they leave."

With no real jobs market, the ghettos keep the local economy ticking over. Migration brings millions of dollars to Agadez. The 30 or so young men leaving aboard two pick-up trucks from Ousseni's migrant 'ghetto' have each paid around 150,000 CFA francs (£163, $249, €228) to travel to Sabha. The journey across Niger can cost 250,000 CFA francs once transport, food, lodging and bribes are taken into account.

Rhissa Feltou, the mayor of Agadez, says the presence of migrants fuels problems in the town, including crime, drug trafficking and prostitution. "We hear many accounts, quite often that there really are tragedies happening in silence. The European Union ... have a duty to go beyond the seas and explore the issue in its entirety. There's a whole chain that needs help, not only the Mediterranean, but also the desert areas.

"The desert has always been a cemetery for immigrants, in silence and complete indifference. Travellers tell us they often find bodies – skeletons ravaged by the sands," he said.

The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime estimates migrant smuggling in Libya may be worth more than $300m a year.

Smuggling rings have profited from lawlessness in Libya to ferry tens of thousands of people to Europe in unsafe boats. The migrants are first brought to Libya from across sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East.

Giuseppe Loprete, International Organization for Migration (IOM) head of mission in Niger, said there was little Niger could do to stop the flow of migrants as many came from countries in west Africa's ECOWAS bloc which allows freedom of movement between its 15 member states, such as Nigeria, Mali, Gambia and Senegal.

According to the latest IOM figures, an estimated 38,000 migrants crossed the Mediterranean into Italy between January and mid-May, with the largest numbers coming from Eritrea, Somalia and Nigeria, followed by Gambia, Syria, Senegal and Mali.

The migrants are often abused by traffickers who abandon them to die in the desert if they run out of money. Smugglers sometimes imprison migrants and force their families to pay for their release, Loprete said. Migrants are often obliged to pay not only the smugglers but also bribes to security officials along the route.

"The moment they have no more money, they are left behind," Loprete said. "People are dying in the desert as well as at sea. In fact, I would be surprised if it was not more than in the Mediterranean."

"In the desert, there are a lot of problems," said Adama Diaw, 30, a Senegalese woman who migrated to Algeria in 2008 with her husband hoping to reach Europe, but is returning home without him. "They lock people in cages, three or four people for days, until you don't know if they are dead. If they die, they just burn the bodies," she said at an IOM migrant centre in the Niger capital Niamey.

Loprete said the IOM is launching EU-funded programmes to educate migrants about the risks of the trip and the difficulties of life in Europe, using radio shows and getting former migrants to talk to them. "The smugglers tell them it is just 15 kilometres from Libya to the Italian coast – but it is more like 300," Loprete said.

Young men waiting in Agadez and other desert towns were at risk of recruitment by Islamist groups in the Sahara, Loprete said.

"To stop these migrant flows at the border would only generate more problems," he said, adding that the real issue was the lack of work in their countries of origin. "We need to finance development programs at a community level so that there is not such an incentive to try to migrate."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.